On February 16th, 2024, at 14:19 Moscow time (11:19 GMT), the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug announced that Alexei Navalny had died in prison, where he had been serving out a 19-year sentence since early 2021. A well known and longtime opposition leader of current Russian president Vladimir Putin, his death, and its circumstances, brought about protests across the world, and further scrutiny of Putin’s administration.

Alexei Navalny’s political history in Russia was quite prominent, as he led various parties and ran for various high-ranking positions within the government. Navalny’s presence made him a well known figure in Russian politics, making many allies and enemies along the way. Though he became a popular representation for Putin’s political opposition, he was far from what many would consider a “flawless candidate,” with several stains on his reputation that would continue to haunt him throughout his life.

But how did the lawyer from Obninsk rise through the ranks of the Russian political sphere? How did he garner his reputation, and how did he make his enemies? How did he end up in a corrective colony in the Russian Arctic?

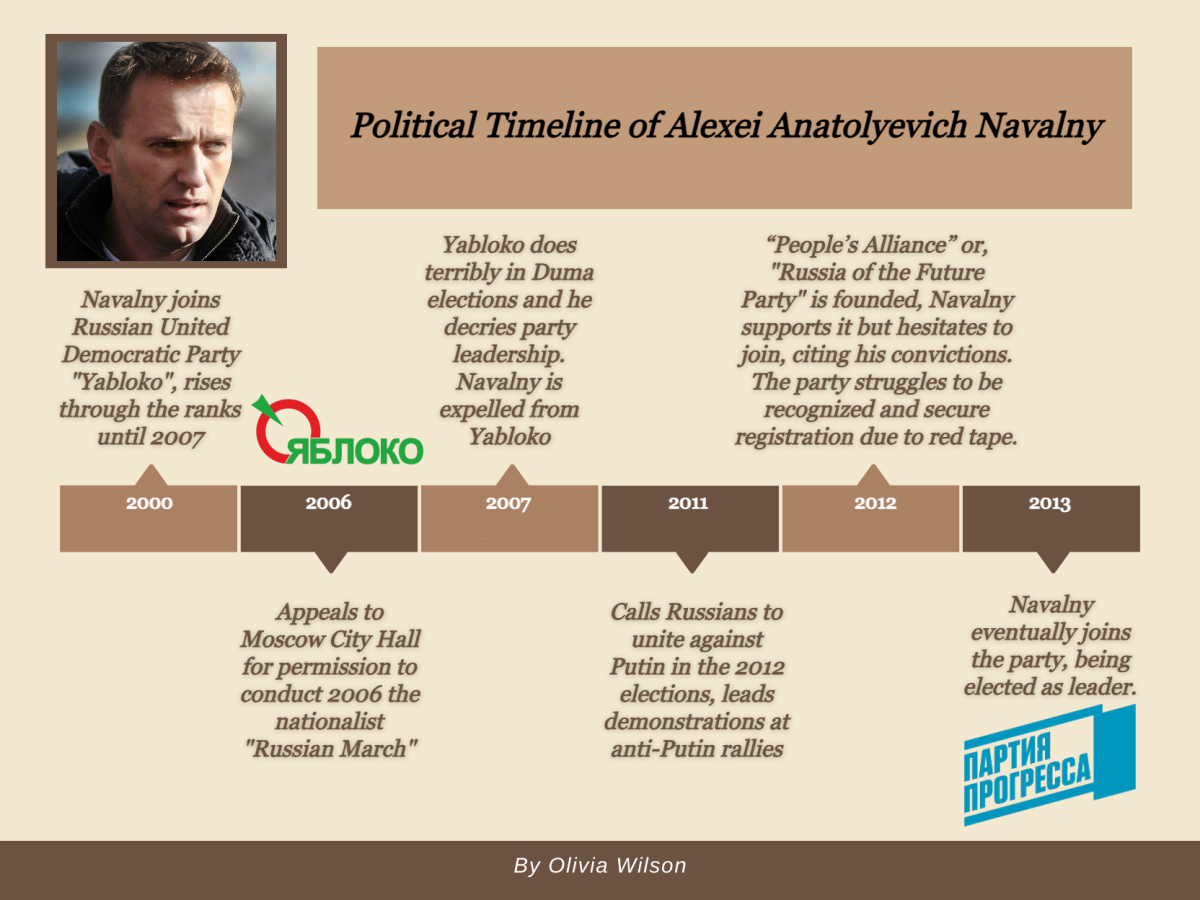

His career in politics began in 2000, after a new law had been announced, raising the electoral threshold for political parties, essentially making it harder for smaller parties to enter the State Duma. Navalny joined the Russian United Democratic Party, also known as “Yabloko.” It was immediately clear to him that the new law was directed at Yabloko, encouraging him to take a more active role in the party, despite him claiming in an interview with Russian Business magazine Vedomosti that he “wasn’t a big fan of Yabloko.” He remarked, “I thought, I’ll just take it and join on principle.”

During his time in the party, Navalny also worked vigorously to encourage public debate among the Russian public. Working as an activist, for relatively little pay, he created the youth social movement, “Da! – Democratic Alternative.” Using grants and donations, the project hosted public debates which became quite popular, resonating with many. The project was soon shut down after provocations during the debates, and prohibition of certain individuals on television by the Russian government.

In 2006, Navalny appealed to Moscow City Hall for permission to conduct the 2006 Russian March, an annual demonstration of Russian nationalist groups. This alignment with the nationalist movement garnered a certain level of scrutiny, forcing him and the Yabloko party to declare that, “Yabloko condemned any ethnic or racial hatred and any xenophobia” and called on the police to oppose “any fascist, Nazi, xenophobic manifestations.” However, the affiliation as a Russian nationalist would continue to hang over Navalny’s head, ostracizing certain supporters of his.

In 2007, Yabloko would lose in the Russian State Duma elections with an embarrassing 1.6% of the vote. Navalny heavily criticized the party, calling for the resignations of numerous party members. These actions would culminate in his termination from the Yabloko party, simultaneously expelling him for his nationalistic views, as shown in the previous year.

Despite his expulsion from the Yabloko party, Navalny continued being active in politics, protesting against corruption and fraud during the parliamentary elections, and against Vladimir Putin, who Navalny predicted would run. He would organize rallies and demonstrations against Putin, both before and after he was inaugurated. This would lead to him being arrested during an anti-Putin rally, and receiving a 15-day prison sentence. For this, Amnesty International designated him a Prisoner of Consciousness, or in other words, someone who was prosecuted for their political beliefs.

In 2012, some of Navalny’s associates such as Vladimir Ashurkov, would found “The People’s Alliance,” a centrist political party. Navalny would be invited to join, but was hesitant to do so, believing his membership would make things complicated for the party, as past legal cases from before his life in politics continued to haunt him. Navalny soon conceded, joining the party in late 2013, where his predictions became true soon after. Though the party struggled to officially register itself, having to constantly jump through legal hoops, Navalny would eventually be elected as leader of the party.

In June of 2013, the mayor of Moscow would no longer be appointed, but elected. Seizing the opportunity, Navalny announced that he would be running for Mayor under “The People’s Freedom Party,” becoming one of the now six candidates for the position. Predictably, the next day his criminal charges returned once again to haunt him, resulting in a 5 year sentence for embezzlement and fraud. Navalny would drop out of the race, calling for a boycott against it. This was soon undone, as the European Court of Human Rights believed denying him from the election would violate laws guaranteeing candidates equal access to the electorate.

Despite the recent change in fortune, Navalny would nonetheless lose the election. Original projections by the All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion put Navalny’s electoral rating at 11%, significantly lower than the final 27% of the vote Navalny would end up securing. Although Navalny’s results were better than most expected, the vote was not close enough to trigger a runoff election, resulting in the election of Sergey Sobyanin.

Many also considered the election to be fair and generally free of any irregularities, though Navalny would still go on to reject the tally, refusing to recognize the results of the election. He would challenge the results before the Supreme Court of Russia, who would ultimately decide against him.

After the election, Navalny was recognized as a key ally as an opposition leader against Putin’s administration. He continued to work for the People’s Freedom Party, and was invited to become the co-chairman in 2014. The party was in favor of the “European Choice,” hoping for Russia to eventually become a member of NATO and the European Union. This opposition party hoped to unite all pro-European opposition entities under one coalition. This project was organized and supported by high ranking party leaders Boris Nemstov and former prime minister Mikhail Kasyanov.

Tragically, in February of 2015, Boris Nemstov would be assassinated, shot dead in Central Moscow. The party however was unexpectedly undeterred, speeding up work to unite Putin’s enemies against him.

In December of 2016, with growing support behind him, Navalny announced that he intended to run in the 2018 presidential election against Vladimir Putin. The move was unprecedented in Russia, as traditionally candidates did not start campaigning until a few months before the election. This was more than necessary, as Navalny’s campaign would need the extra months to garner support among the Russian population.

Navalny continued to represent his longtime values, calling for a peaceful Russia, free of corruption. He also advocated for greater diplomatic and economic cooperation with Western Europe, regulation of workers from bordering central Asian countries, and to repeal Russia’s established anti-LGBTQ legislation.

According to Western publications Freedom House and The Economist, Navalny was the most threatening opposition candidate against Putin. But despite all this, even with increased public attention, the Leninsky district court of Kirov repeated its sentence of 2013 (after the case had been sent to a new trial with a different judge by the Supreme Court, annulling the initial sentence after the decision of the ECHR, which ruled that Russia had violated Navalny’s right to a fair trial, in the Kirovles case) and re-sentenced him with a five-year suspended sentence.

Once again, Navalny’s past convictions would conveniently halt his work against Putin’s administration. Navalny promised to fight the sentencing, and over the next few months organized various illegal protests, for which he was subsequently but briefly arrested.

In December of 2017, Russia’s Central Electoral Commission officially barred him from entering the presidential election based on his corruption charges. Navalny in turn called for a boycott against the election, continuing his protests and demonstrations. He would file for an appeal to the Russian Supreme Court, but was denied.

It’s hard to say whether he ever had a fair shot at winning the election. According to Dr. James Rodgers, of the City University of London, it’s “difficult to gauge the true extent of Navalny’s popularity. The authorities never let him run for president. That shows they were worried. But it is not clear he could have won an election even in a fair system. That does not mean to say he did not have support, just not necessarily a majority.”

This would end Navalny’s major role in Russian politics, as he could no longer run for any major political position. A few years later in 2021, he would be detained and received a prison sentence for 2 ½ years in a corrective labor colony. The sentencing was unsurprisingly denounced by many Western countries. A year later the sentence would be extended under charges of embezzlement and contempt of court, though Amnesty International would call the trial a “sham.”

Navalny would die in prison a few years later, aged 47. But how does this affect Putin’s current administration? According to Dr. Rodgers, Putin’s grip on power in Russia shows no signs of weakening. He goes on to say that, “Navalny’s death has shown the risks you take if you challenge Putin. Now all of the prominent opposition are either in jail, in exile, or dead — and others are keeping quiet. There is no organized opposition to speak of. That does not mean no one opposes Putin. It is just impossible to express opposition openly.”

In Russia today, organized opposition against this particular incumbent, Putin, is practically impossible.

Despite any number of actions made by international parties, the authorities find a number of means to silence critics — from keeping them out of the mass media, and denying them the right to register as candidates, to jailing and even death. President Biden made it clear he believed Putin was responsible for Navalny’s death. More economic sanctions have been imposed on Russia. But in the short and medium term, barring some unforeseen catastrophe in Russia, Putin looks secure, whatever actions other countries take.

Despite this, looking back on the life of Alexei Navalny, we can recognize him as a pivotal figure in Russian political history. He embodied resilience, courage, and unwavering commitment to democratic principles despite relentless bureaucratic and legal harassment. From his early years as an activist against government corruption, Navalny navigated a treacherous path, facing persecution, imprisonment, and even death. Yet, his unwavering commitment to a new Russia inspired countless Russians to demand more from their government. As the international community continues to rally behind his cause, Navalny’s legacy as a symbol of resistance against oppression will endure, echoing the timeless struggle for freedom and democracy worldwide.

Looking back on the life of Alexei Navalny, we can recognize him as a pivotal figure in Russian political history. He embodied resilience, courage, and unwavering commitment to democratic principles despite relentless bureaucratic and legal harassment.