How One Adoption Case Could Upend Native American Rights

The Indian Child Welfare Act has been considered one of the most important laws for Indigenous children in America. Last year, a Supreme Court case attempted to get it overturned.

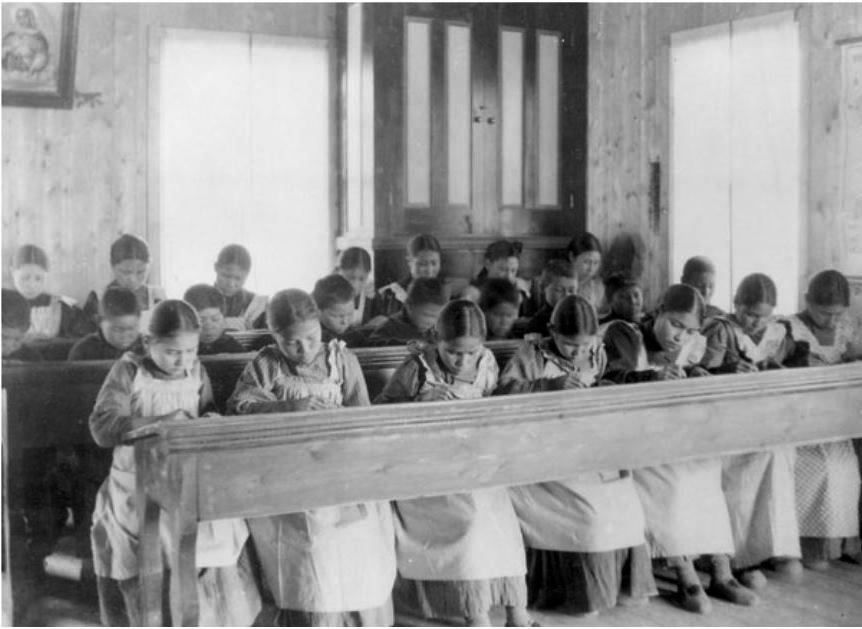

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada/PA-042133, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Students at a Residential School in Canada. The identical uniforms and hairstyles in this photo reflect the conformity taught at these institutions.

Three consolidated adoption cases reached the Supreme Court on November 9th of last year. The plaintiffs – the state of Texas and three white adoptive parents – want to overturn a half-century-old adoption law. The defendants, including U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland and the Cherokee Nation, argue that overturning this law would be a deadly blow to Native sovereignty.

The law is the Indian Child Welfare Act, and the case is Haaland v. Brackeen.

The law, referred to as ICWA, has been in place since 1978 when, after decades of Indigenous children being removed from their families, the federal government finally decided to intervene. ICWA mandates that Native kids (children who, through their parents, are eligible for tribal membership) in foster care go to Native families whenever possible.

When looked at more closely, Haaland v. Brackeen is a trojan horse. At the surface level, it’s about four children. Digging deeper, this case has the potential to impact thousands of Native kids across the country. But the root of this case, the army inside the gift horse, is that Haaland v. Brackeen will set a new precedent for how the federal government regulates tribal affairs, and this new precedent could change everything for Indigenous Americans.

With that said, this case is incredibly dense. The history surrounding ICWA is convoluted and upsetting, and complicated. But America needs to start paying attention to Indigenous issues, even when (especially when) they’re complex.

UNDERSTANDING ICWA’S HISTORY

The Indian Child Welfare Act was the U.S. Government’s belated response to a century of residential schooling and unwarranted family separation.

In 1869, the United States and Canada collaborated with the Catholic Church to create the residential school system. These schools were explicitly designed to assimilate Indigenous children into white society. Attendance at residential schools was compulsory, and Native parents could be jailed for keeping their children home. But some parents didn’t even have to be forced — Native communities were robbed of their natural resources, and parents were told that the best way to keep their kids safe was to send them away.

These schools didn’t keep anyone safe. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada found that at the very least, 3,000 students died from disease, overcrowding, poverty, or malnutrition. A government medical inspector found that in the early twentieth century, 24% of previously healthy Native children were dying in Canadian residential schools.

In the US, as of 2022, the bodies of 500 children have been uncovered at 19 schools. The Department of the Interior says these numbers are likely much lower than the actual death toll, which is projected to be in the tens of thousands. In Canada, over 1,700 unmarked graves were found near seven residential schools.

Native children who survived were stripped of their culture and humanity. These schools knew that a lot of Indigenous Nations place significance on long hair and traditional clothing, so they took both. Some schools even took the children’s names, referring to them by numbers for the years they spent there. Speaking anything but English was forbidden, and generations lost fluency in their native languages. By 18, most didn’t get beyond an elementary school education — they were busy working, getting ‘practical experience’ through forced, unpaid labor, farming, and cleaning.

The last residential schools stayed open until 1969. Historians estimate that around 150,000 Indigenous children went to residential schools during the century they were open.

The closure of residential schools wasn’t the end of Indigenous family separation. State foster agencies started to use (and still use to this day) allegations of abuse and neglect to take Native kids from their homes. Abuse and neglect are subjective terms, laden with loopholes, and a lot of what foster agencies label as neglectful or abusive parenting is really just cultural differences or poverty.

But Native kids’ placement in foster care is grimmer than just mislabeled neglect. State foster systems actually have a financial incentive to take Native kids from their families.

National Public Radio reports that the South Dakota state foster system gets financial ‘incentives’ from the federal government when kids in foster care are adopted. Most of the time, this bonus is $4,000, but for kids labeled as ‘special needs,’ the bonus is $12,000 – and South Dakota has inexplicably labeled all Native kids ‘special needs’ regardless of disability. Every time a Native kid is placed in a permanent adoptive home, the agency gets $12,000, triple what that agency would get for a non-Native kid. The vast majority of these kids are adopted by white parents.

On the flip side, in 2011, South Dakota made $79,000 per child every year a Native American was in foster care.

There’s an incentive to keep them in care, and there’s an incentive to adopt them out of care. The one thing there’s no incentive for? Reunification.

Despite the targeted removal Native families experience today, it’s clear that ICWA is making a difference. A 2020 study found that ICWA has a positive effect on reunification rates and trial speed. ICWA also has widespread support in Native and non-Native communities. Last year, a bipartisan group of almost 90 Congresspeople filed a brief to the Supreme Court in support of ICWA signed by almost 500 different tribes, 67 Indigenous organizations, and 20 states.

ICWA has been vital to Indigenous populations for decades. Haaland v Brackeen has the power to take that away.

THE CASE

Haaland v. Brackeen involves four children, three plaintiffs, and over two centuries of legal precedent. The adults in this case are referred to by their real names, but the children are given pseudonyms to protect their privacy.

The only active case is that of Jennifer and Chad Brackeen, Evangelical white foster parents who adopted a Navajo boy, A.L.M., and are in the process of adopting his half-sister, Y.R.J. The Navajo Nation contested the adoption, and the Brackeens sued for racial discrimination, arguing that they were denied custody solely due to their race. Although this case is active, the Supreme Court cannot override state custody decisions – which means that even if the Brackeens win, there’s no guarantee that they’ll have custody over Y.R.J.

The other two plaintiffs, the Librettis and the Cliffords, also won’t see any change in their living situations based on this ruling. The Librettis have full legal custody of their child, Baby O, as per the wishes of O’s mother. The Cliffords wanted to adopt a Native child, called P.S., who they had been fostering, but lost their court case to Robyn Bradshaw, P.S.’s biological grandmother and a member of the White Earth Band of the Minnesota Chippewa tribe.

The plaintiffs, at first glance, don’t get anything out of this case – so why have they spent the time, energy, and money to go to the Supreme Court?

First of all, they haven’t actually spent any money. The plaintiff’s lawyer, Matthew McGill, a partner at Gibson Dunn, is doing the case pro bono. Gibson Dunn also happens to do much of its work with oil companies like Enbridge, responsible for Line 3, and Energy Transfer Partners, responsible for the Dakota Access pipeline. Gibson Dunn makes a large portion of its money from companies that put pipelines on Native land. It makes sense, then, that they could have an incentive to take on cases that challenge Native sovereignty.

As for time and energy, the families involved in this case consistently assert that their experience made them less likely to adopt Native American children again, and they want to remedy the issues they faced.

The plaintiffs’ main argument against ICWA is an equal protection challenge. ICWA mandates that Native children be placed with other Indigenous people whenever possible – first placement preference goes to biological family, then members of the child’s tribe or nation, then members of other tribes, usually those living on the same reservation. The Brackeens say that this distinction is racial and that the law should be stricken for discrimination. During his oral arguments at the Supreme Court, Ian Gershenhorn, a lawyer representing the tribal parties, disagreed.

IAN GERSHENGORN: “Plaintiff’s equal protection claims should be rejected… ICWA draws distinctions that are political three times over; it applies only to tribes that the federal government has recognized, it incorporates membership criteria established by sovereign tribes, and it relies on the political decisions of parents to remain tribal members.”

This argument – whether tribes are political groups or racial ones – has impacts reaching far outside adoption law. A 1974 Supreme Court case, Morton v. Mancari, defined tribes as political groups, and most tribal laws since then rely on that distinction. If Indigenous people are considered a racial group, it wouldn’t just end ICWA. It would kill decades of essential legislation.

In an interview with The New York Times, Robert Miller, professor of federal Indian law, tribal court judge and member of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe, described his fears about the case.

ROBERT MILLER: “It would put at risk every treaty, every property and political right and every power that Indian nations possess today… your borders, your police laws, everything on the reservation would be in question. I’m not being hyperbolic. I am afraid of this case.”

Even without the equal protection debate, the plaintiffs have two other arguments against ICWA – one of which centers on states’ rights.

Congress, and the federal government as a whole, is supposed to stick to legislating certain topics so that the rest can be left to the states. The Constitution and its amendments give Congress ‘plenary power,’ or the ability to legislate across the board on certain issues. Judd Stone, a lawyer representing the Brackeens, argues that adoption law should be left to the states, and by legislating on a national level, ICWA violates states’ rights. Justice Kagan rebuts this, clarifying that Indian affairs are in Congress’ jurisdiction – including adoption law. Kagan’s interpretation is shared by defense lawyer Ian Gershenhorn.

IAN GERSHENGORN: “Congress has plenary power over Indians and there is no exception in that power for state court child custody proceedings. Since the founding [of this country], the health and safety of Indian children have been the province of the federal government and tribes, not the states.”

The final debate against ICWA is whether or not it serves the best interests of children. The law prioritizes cultural and political ties over factors like financial status, and some opponents are concerned that children will have a poor quality of life with other tribe members. Justice Sotomayor took issue with this argument.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: “All of these parents, to even be in the running, have to be competent parents, correct? So now the issue is one of policy. Where will you place the child among these competing competent custodians…”

Edwin Kneedler, representing the federal government, adds to this point. He argues that ICWA was set up to combat bias against Indigenous parents, and was specifically designed to protect the best interests of both the child and the tribe.

EDWIN KNEEDLER: [Congress] determined… that the framework that it set up in ICWA was in the best interests of the child because… placing the child with the extended family, [or] with the tribe, which is a kinship community interest… was in the best interests of the child…”

From these statements, it seems clear – ICWA doesn’t hinder the best interest of the child at the expense of the tribe, it simply acknowledges that between two competent parents, a parent with locational and cultural ties is better for the child than one with slightly more money.

A WORLD WITHOUT ICWA

The court’s decision is supposed to come out by June of this year – what happens if the plaintiffs win?

We’re told Haaland v. Brackeen is about four children finding homes. It’s about much more than that. This case is a turning point in Indigenous history – one that could solidify tribal sovereignty, or dismantle it.

It’s about every Native kid in America, and whether they could be taken from their families, whether they could be systemically stripped of their culture. It’s about every Native person in America, and whether they could lose the legal protections they’ve had for the last sixty years. It’s about every reservation in America, every tribe in America. It’s about what could be taken away next.

The real impact of this horse passing the gates of Troy is the tidal wave on its heels.

UPDATE: On June 15th, 2023, the Supreme Court released its decision in the case of Haaland v. Brackeen. Those following the case have been waiting for months for the decision — some of us were hopeful, some of us less so. But the ruling is a ground-breaking victory — the Supreme Court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act as constitutional law. Justice Amy Coney Barrett delivered the majority decision, representing the 7 justices who supported ICWA. Both Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito wrote their own dissents. This decision is largely due to the diligent efforts of the two lawyers representing the tribes and the tireless organizing of Indigenous American activists. The victory in Haaland v. Brackeen is cause for celebration — a huge (shocking) win for Native American children and families.

We’re told Haaland v. Brackeen is about four children finding homes. It’s about much more than that. This case is a turning point in Indigenous history – one that could solidify tribal sovereignty, or dismantle it.

Acadia Bost is a returning Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ Placing an emphasis in their writing on the more structural, long term problems...