Madeleine Albright, Democracy’s Strongest Defender, Dies at 84

The nations’ first female Secretary of State leaves behind a golden legacy which emphasizes the value of fighting for human rights, freedom, and democracy.

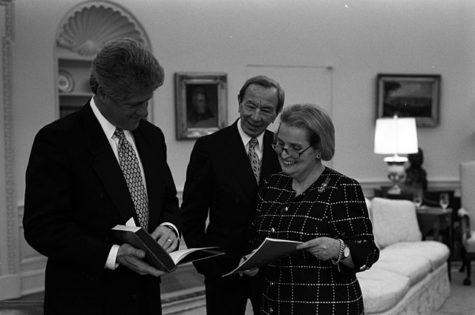

Ms. Albright shortly after assuming a position as a foreign policy advisor for Michael Dukakis’ campaign.

“Our nation’s memory is long and our reach is far,” Madeleine K. Albright, the United States’ first female secretary of state wrote. At the head of the negotiating table and the helm of international affairs, Albright worked tirelessly to realize her dream of a more peaceful, prosperous world.

A fearless fighter for freedom and determined defender of democracy, Ms. Albright died on March 23rd, 2022, in Washington after a battle with cancer. She was 84.

Early Years

Madeleine Albright was born as Marie Jana Korbelova in Prague on May 15th, 1937 to parents Joseph and Anna Korbel. Her father was a press attache in the Czech Embassy in Yugoslavia and advised two successive Czechoslovakia’s presidents: Tomas G. Masaryk and Edvard Benes.

Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland and invasion of Czechoslovakia placed a death warrant on the Korbel family’s door. After ten days in hiding, Mr. Korbel fled to London and began working for Benes’s government in exile.

As a young girl, Ms. Albright spent long nights in shelters as the Germans dropped bombs during the Luftwaffe air raids. Her wartime memories remained with her her entire life, motivating her work to preserve peace and protect human life through robust foreign policy initiatives.

In 1941, in the face of the threat of persecution, the Kobels made the devastating decision to convert to Roman Catholicism. They baptized their children, attended church services, and adhered to all conventional Christian practices.

“I think my father and mother were the bravest people alive,” Ms. Albright told The New York Times in 1997. “They dealt with the most difficult decision anyone could make. I am incredibly grateful to them, and beyond measure.”

Thus, Ms. Albright grew up oblivious to her Jewish heritage, protected from the senseless violence of the Nazis by her parents’ fabricated Christian memories. “My parents talked about how they met, and how they were high school sweethearts. They talked about getting ready for various holidays, for Easter and Christmas.”

Ante bellum, the Korbels returned to Prague and Mr. Korbel assumed the position of Czech ambassador to Yugoslavia. Dipping her toes in the shallow end of diplomatic waters, Ms. Albright would present herself in “Czech national costume when foreign visitors came to Belgrade” and offer them flowers.

In 1948, communists claimed control in Prague, endangering the Korbel family once again. Mr. Korbel joined a UN commission and fled with his family to America where he earned a position as a professor at the University of Denver. Ms. Albright attended the Kent School for Girls where, in future-secretary-of state-like fashion, she founded an international relations club. She then studied political science at Wellesley College and married Joseph Mill Patterson Albright, the wealthy grandson of the founder of The Daily News of New York.

Her introduction to politics came in the form of fundraising. In 1972, Ms. Albright began raising funds for the presidential campaign of Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine, a family friend for whom she served as a legislative aide. She then became a counselor to President Jimmy Carter and a foreign policy advisor to three presidential candidates: Gov. Michael S. Dukakis of Massachusetts, Senator Walter F. Mondale of Minnesota, and Bill Clinton.

When Mr. Clinton assumed office as president in 1993, he named Ms. Albright as chief delegate to the United Nations. She wielded her brilliant global affairs analysis skills to promote U.S. interests globally. However, Ms. Albright and Mr. Clinton encountered international trouble spots in terms of peacekeeping operations in Somalia, Rwanda, and the Bosnian civil war.

In the weeks before Clinton assumed office, President George H.W. Bush had placed American troops in Somalia to provide food to the victims of a brutal famine in the midst of civil war. However, when a Somali warlord killed eighteen American troops and an image of a dead helicopter pilot circulated the media, Clinton withdrew all U.S. forces to avoid further stains on his foreign policy record.

Avoiding further UN peacekeeping operations, the United States stood idle as the Rwandan genocide unfolded in 1994. Approximately 800,000 Tutsi were murdered in this government sponsored killing spree. While initially Ms. Albright blamed Mr.Boutros-Ghali, the UN’s Secretary-General, for his disengagement and inaction, she later wrote in her 2003 memoir: “My deepest regret from my years in public service is the failure of the United States and the international community to act sooner to halt these crimes.”

Mr. Boutros-Ghali also observed: “A genocide in Africa has not received the same attention that genocide in Europe or genocide in Turkey or genocide in other parts of the world. There is still this kind of basic discrimination against the African people and the African problems.” Pinpointing the racist undertones of American foreign policy, Mr. Boutros-Ghali expressed a commitment to preventing future outbreaks of violence.

Importantly, Mr. Boutros-Ghali later clashed with Mr. Clinton and Ms. Albright over the Bosnian civil war, a vicious conflict rooted in ethnic and religious fissures which fractured the nation and facilitated ethnic cleansing campaigns against Muslims and other minorities. While the U.S. initially only engaged in limited airstrikes, the Clinton administration eventually mediated the conflict.

Still, the bitter animosity between Mr. Boutros-Ghali and Ms. Albright and Mr. Clinton motivated Ms. Albright to cast a veto when the Security Council voted (14-1 with Albright’s sole no) to give Mr. Boutros-Ghali a second term. Mr. Boutros-Ghali decreed that this veto was both a great insult and an unscrupulous political maneuver.

Madame Secretary

“To defeat the dangers and seize the opportunities, we must be more than audience, more even than actors, we must be the authors of the history of our own age,” Ms. Albright asserted in her opening remarks after Mr. Clinton nominated her to be the first ‘Madame Secretary.’

Ms. Albright assumed the position with a robust foreign policy agenda in mind. Her chief aim was to create “an integrated, stable and democratic Europe” by enlarging NATO. Moreover, she emphasized the importance of “a strong bilateral relationship between the United States and China,” a wish which has fallen into the void in our current climate of heightened tensions.

Arms control and nonproliferation was another one of Ms. Albright’s central goals. “The Cold War may be over, but the threat to our security posed by nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction has only been reduced, not ended,” she said. Thus, Ms. Albright encouraged the United States to cooperate with Russia to guarantee the success of the START II Treaty.

Her ambition to expand American economic hegemony motivated Ms. Albright’s desire to open markets abroad and promote free trade. Lastly, she also took a hardline stance on human rights, vowing to combat international terror, narcotics, and human trafficking.

Uniquely, Ms. Albright aimed to bring foreign policy to the forefront of the American conscience. “As secretary, I will do my best to talk about foreign policy not in abstract terms, but in human terms and bipartisan terms. I consider this vital because in our democracy, we cannot pursue policies abroad that are not understood and supported here at home,” she said.

This policy aligned with Ms. Albright’s firm belief in the importance of individual agency as a catalyst for social change. “The real question is: who has the responsibility to uphold human rights?” She asked, “The answer to that is everyone.”

Thus, radiating a cosmopolitan flair, she embarked on a nine-nation world tour, stopping in Brussels, Rome, Bonn, London, Paris, Moscow, Seoul, Tokyo, and Beijing. Ms. Albright laid a strong foundation for diplomatic efforts and generated excitement, airing a star quality, from country to country. In an age where Ms. Albright observed that “People are finding it harder and harder to relate to foreign policy,” she aimed to connect to not only leading diplomats but also native populations, extending a warm smile and displaying her linguistic talents to all.

During comparatively peaceful and prosperous years, Ms. Albright dealt with conflicts in Northern Ireland, Kosovo, Haiti, Bosnia, and the Middle East. Additionally, Ms. Albright spearheaded the expansion of NATO into Eastern Europe. In 1999, the alliance admitted Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary into its ranks.

“The debate about NATO enlargement is really a debate about NATO itself. It is about the value of maintaining alliances in times of peace and the value of our partnership with Europe. I am a diplomat. And I know that a diplomat’s best friend is effective military force and the credible possibility of its use. That has been the lesson of the Gulf War and Bosnia and all through history. And that is a lesson we must remember in Europe, where we will still face threats that only a collective defense organization can deter,” said Ms. Albright in a statement to the Senate Armed Services Committee.

While arguments against the expansion of NATO have arisen once again following Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Mrs. Clinton recently wrote in The New York Times that “As the Princeton historian Stephen Kotkin has noted, that argument ignores Russia’s centuries-long efforts to dominate its neighbors.” Many allege that Ms. Albright rightly feared for continued Russian encroachment in Europe, justifying an enlarged and united NATO.

Importantly, Ms. Albright also continued economic sanctions against Iraq. However, in late 1997, Saddam Hussen blocked United Nations inspectors from accessing sites where chemical and biological weapons were believed to be housed. In the face of this blatant violation of a Security Council resolution put forth during the Persian Gulf war, the Clinton administration threatened to attack Iraq if UN inspectors could not monitor weapons of mass destruction development.

In an interview with Matt Lauer, Ms. Albright stated: “I think that we know what we have to do, and that is help enforce the UN Security Council resolutions, which demand that Saddam Hussein abide by those resolutions, and get rid of his weapons of mass destruction, and allow the inspectors to have unfettered and unconditional access. That’s what we have to do. Matt, we would like to solve this peacefully. But if we cannot, we will be using force; and the American people will be behind us, and I think that they understand that.”

Fortunately, the UN secretary general, Kofi Annan, forced Saddam Hussein’s hand, guaranteeing unrestricted access to the sites by UN inspectors. Still, in 1998, the US and Great Britain bombed Iraqi military targets as a means of decimating Iraq’s ability to create weapons of mass destruction.

Beyond the crisis in Iraq, Ms. Albright advocated for the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol regarding climate change, sought to curtail the proliferation of nuclear weapons in volatile states such as North Korea, and passionately defended the 78-day NATO bombing campaign in Kosovo which prevented Yugoslavian forces from massacring Albanians.

“The most vivid recollection is actually the night of the bombing. You can talk about the use of force. When you actually use it, you think about the pilots, the people on those airplanes, going into very dangerous territory where there are air defenses. I feel the responsibility. It’s one thing to go to meetings and talk. It’s another thing when the airplanes go in, and you know that you played a role in this, that there are Americans or allies in those planes, that you are bombing, and that there are people on the other end of it. You keep in mind the larger goal, and that you sometimes have to take difficult steps like that to save lives, and to protect American values in our national interest,” Ms. Albright recalled, exemplifying the difficult decision making processes she faced as the nation’s most decorated diplomat.

Ms. Albright also worked tirelessly to hold all perpetrators of war crimes accountable for their deleterious actions. She attempted to bring justice to Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic and the wartime Bosnian Serb leader, Radovan Karadzic. While Ms. Albright’s legacy is deeply tarnished in Serbia, she is regarded as a hero in Kosovo and Bosnia. Monuments have been erected in her honor in Kosovo, whereas a snake was named after her in Serbia.

“She will be remembered in Serbia as a ruthless woman, one of the loudest advocates of the bombing of Yugoslavia and the independence of Kosovo,” a pro-government Serbian newspaper decreed.

Ms. Albright garnered further criticism when American diplomats in Africa accused her of failing to act upon warnings that ominously hinted at the possibility of the truck bombings in 1998 that killed 224 people at American Embassies in Tanzania and Kenya. In Washington, President Bill Clinton vowed to “use all the means at our disposal to bring those responsible to justice, no matter what or how long it takes.”

Additionally, despite employing her most firm and flexible negotiating skills, Ms. Albright failed to strike a deal to curtail Kim Jong-il’s ballistic missile program in North Korea.

However, throughout her tenure as Secretary of State, Ms. Albright garnered the highest praise from diplomats and politicians worldwide. Ms. Albright firmly advocated for Mr. Clinton’s policies, radiated a practical, pragmatic diplomatic approach which could endear her to even the most staunch dictators, and prized a people-oriented approach which encouraged individual attention and investments in foreign policy developments.

Confident and cosmopolitan, dignified and diplomatic, Ms. Albright governed the oval-table and dominated international affairs. “So often in diplomacy, it’s all set pieces. You say this and I say that and the meeting ends and nothing happens. But she engages. And in contrast to nearly all her predecessors, she doesn’t hide policy differences, but brings them out, and speaks very directly of them, saying things like ‘Here’s what we agree on, here’s what we don’t. Let me tell you what the real problem is,’” an aide told The New York Times.

In 2001, Ms. Albright stepped down as secretary of state. While some believed she would enter politics in the Czech Republic, she instead founded the Albright Stonebridge Group, an international consulting firm and in 2005 she founded Albright Capital Management. She also taught at Georgetown University and served as a director of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Ms. Albright took to writing, proving her literary virtuosity. Along with her 2003 memoir, Ms. Albright published “The Mighty and the Almighty: Reflections on America, God and World Affairs” (2006) which outlined the connection between religions and politics in the framework of American democracy. She then wrote ““Memo to the President-Elect: How We Can Restore America’s Reputation and Leadership” (2008), “Read My Pins: Stories From a Diplomat’s Jewel Box” (2009) and “Prague Winter: A Personal Story of Remembrance and War, 1937-1948” (2012).

Her 2012 autobiographical book revealed her familial secrets which she had uncovered in the 1990s through a series of letters from Europe with information regarding her family’s true history. “I was fifty-nine when I began serving as U.S. secretary of state. I thought by then that I knew all there was to know about my past, who ‘my people’ were, and the history of my native land. I was sure enough that I did not feel a need to ask questions. Others might be insecure about their identities; I was not and never had been. I knew. Only I didn’t,” she wrote on the first page of her memoir.

Her last book “Fascism: A Warning” (2018), was written in conjunction with Bill Woodward and sounded the alarm regarding the rising threat of fascism worldwide. In an interview with Sean Illing, Ms. Albright explained the reasons for the resurgence of fascist leaders. “Most of us were looking toward a system that had been established after World War II – democratic governments, a globalized economy that would bring the world together – and thought it was remarkably stable. But the situation has gotten more complicated. A lot of people have benefited from globalization, but it has huge downsides. It’s faceless, and people want to know their identity, want to be connected to some religious or ethnic or national group,” Ms. Albright said.

While she acknowledged the non-threatening nature of a desire for identity in isolation, Ms. Albright also recognized the connection between the insularity of identity and hypernationalism. “Suddenly groups are pitted against each other or scapegoated and all of political life becomes tribalized conflict. And we can see this happening in a number of places. Viktor Orbán’s embrace of ethnic purity in Hungary is a good example of this,” she furthered.

Thus, in a rapidly deteriorating political climate, when “some strongman comes along and says, “I have the answers, I can fix everything.”… this is when you get fascism.”

In the book, Ms. Albright also dubbed Donald Trump “the most undemocratic president” in modern American history, warning against the early symptoms of fascism within the world’s leading democracy. She observed in her interview with Sean Illing that “his approach to the free press, to democratic institutions, to the independent judiciary, is extremely dangerous and anti-democratic. And his general disdain for the rule of law is genuinely alarming.”

Still, Ms. Albright remained hopeful about the future global order. However, she maintained that the problems associated with democracy and globalization can only be overcome if global citizens continue to fight for liberty, justice, and equality.

In 2008, Ms. Albright supported her close friend Hillary Clinton for the Democratic presidential nomination. In a guest essay for The New York Times, Mrs. Clinton recalled that Ms. Albright was “wickedly funny, stylish and always game for adventure and fun.” At Wellesley, where the pair were two years apart, they used to exchange letters fondly beginning with “Dear ’59” and “Love, ’69.” However, when Barack Obama won the nomination for presidency, Ms. Albright staunchly supported him.

In 2012, President Barack Obama offered Ms. Albright the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civilian honor.

In 2016, Ms. Albright once again supported Mrs. Clinton for the presidency. At a New Hampshire primary, she decreed that “There’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other.”

While some embraced this line as an appeal to feminist unity, others regarded it as blatantly offensive to women who supported Bernie Sanders. Ms. Albright later apologized in an article in The New York Times. “I did not mean to argue that women should support a particular candidate based on gender. But I understand that I came across as condemning those who disagree with my political preferences. If heaven were open only to those who agreed on politics, I imagine it would be largely unoccupied,” she wrote.

Still, Ms. Albright proved the intersectionality of conventional femininity and power in politics during her tenure as Secretary of State. “I love being a woman and I was not one of these women who rose through professional life by wearing men’s clothes or looking masculine. I loved wearing bright colors and being who I am.”

Ms. Clinton recalled one particular incident in which she consulted with Ms. Albright on a speech she was to deliver at the UN conference at Beijing. Ms. Albright astutely informed Ms. Clinton that she could dramatically strengthen her argument by stating that women’s rights are human rights and human rights are women’s rights.

At Ms. Albright’s funeral, President Biden delivered a moving eulogy commemorating Madeleine Korbel as a burning beacon of light in dark times for democracy. “In the 20th and 21st century, freedom had no greater champion than Madeleine Korbel Albright,” he said.

He then turned to Ms. Albright’s daughters, sitting front row at the cathedral: “Your mom was a force, a force of nature. With her goodness and grace, her humanity and her intellect, she turned the tide of history.”

Now, Ms. Albright leaves behind both a prescient warning and a brilliant vision of a brighter future. Her legacy is a potent reminder that the torch of democracy which aims to light the global stage can only survive if society collectively feeds the flame, forever fighting against the threat of fascism and authoritarianism.

In one of their last phone calls, Mr. Clinton remembered that Ms. Albright dismissed any worries about her health. “Let’s not waste any time on that. The only thing that really matters is what kind of world we’re going to leave to our grandchildren.” Selfless and sage, Ms. Albright points our gaze to the future while deepening our appreciation of the work she completed which propelled us to peace.

Now, Ms. Albright leaves behind both a prescient warning and a brilliant vision of a brighter future. Her legacy is a potent reminder that the torch of democracy which aims to light the global stage can only survive if society collectively feeds the flame, forever fighting against the threat of fascism and authoritarianism.

Katia Anastas is an Editor in Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She loves that journalistic writing equally emphasizes creativity and truth, while allowing...