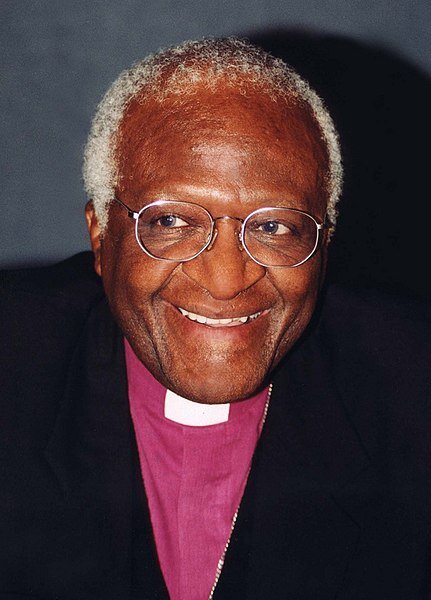

The Life and Legacy of Anti-Apartheid Activist Desmond Tutu

A look into how Desmond Tutu helped to bridge the racial divide in South Africa through his experience as an archbishop and through his powerful speeches.

Since he became an archbishop, Desmond Tutu’s main goal was to unite the Black and White people of South Africa, and when that occurred in 1994, Desmond Tutu continued to fight for justice, becoming the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in order to investigate human rights abuses during apartheid.

Desmond Tutu, an anti-apartheid activist who was also a champion of women’s rights and LGBTQ rights, died on December 26th, 2021, and he was buried on January 1st, 2022 at St. George’s Cathedral in Cape Town, South Africa.

Tutu grew up in an impoverished family. “Although we weren’t affluent, we were not destitute either,” Tutu recalled. As a young child, he suffered from polio, causing atrophy in his right hand. However, neither of these issues stopped him from excelling in school, and he soon realized that he had a passion for English and for teaching.

At the St. Francis Anglican Church where he became the server, he developed a love for reading. He sat for hours, utterly absorbed by comic books and European fairy tales. He was especially influenced by the church’s priest, Trever Huddleston. Shirley du Boulay, Desmond Tutu’s biographer, claimed that Huddleston was the “greatest single influence in Tutu’s life.”

Tutu excelled academically, and his grades were high enough for him to gain admission in order to study medicine at the University of Witwatersrand. However his parents could not afford to pay tuition. So, he decided to become a teacher instead. His first teaching role was at Madibane High School, where he taught English. He would teach English and history in other high schools later on in his career. However, with the introduction of the Bantu Education Act, which mandated racial segregation in schools, Tutu felt like he could no longer teach due to the unfair and discriminatory policies. Thus, he decided to become a priest, with the support of Huddleston.

Throughout the early 1960s and 70s, he was appointed and ordained to many positions within the church. In December 1960, he became an Anglican Priest at St. Mary’s Cathedral. He later went to King’s College London in 1962, in order to study theology for two years. He traveled back and forth between South Africa and London — South Africa in order to give religious tours in his country, and London in order to continue to study theology and religion. He went back permanently to South Africa, in order to serve as the dean of St Mary’s Cathedral, which led him to become the bishop of Lesotho.

Tutu became more aware of the effect that apartheid had on the people of South Africa during this time. In his autobiography, he recalled writing an impassioned letter to the prime minister at the time, B.J. Vorster, about apartheid, stressing non-violent protest and foreign economic pressure, in order to bring about universal suffrage. He argued, that if the government continued to enforce apartheid policies, the country would collapse. Tutu followed this letter with public speeches that he delivered all around the country, stressing the importance of non-violent anti-apartheid efforts, teaming up with leaders such as Winnie Mandela, Nelson Mandela’s wife.

When he became the General Secretary of South African Council of Churches (SACC) in 1978, Tutu was responsible for changing the demographic profile of the Christian Institution. The SACC was one of the few organizations in South Africa in which Black people had majority representation. The constituents of the organization felt a personal connection to him, calling him “Baba,” which meant “father” in their language.

The South African government condemned Tutu’s activism. By 1980, the South African government took his passport after he announced that there should be economic disinvestment from South Africa, because of their participation in apartheid. Tutu, along with Joe Wing, another South African activist, were imprisoned and fined. Once Tutu was released from prison the next day, he traveled to the United States, in order to expand his following. His popularity grew in the 1980s, with him being compared to men such as Martin Luther King, Jr and Nelson Mandela. South African media and news organizations such as The Citizen and South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) vilified him because of his high status, which seemed to contradict the lifestyles of many Black people living in South Africa during that time.

In 1984, Tutu was invited to the White House, where he conversed with then-president Ronald Reagan, whom he did not like at the time. Tutu was not pleased with Reagan’s approach to South Africa, as Reagan sided with the South African government, which was run by Caucasians and created discriminatory policies. Tutu was direct in his dislike: The Reagan administration is “an unmitigated disaster for us Blacks,” he said in an interview in 1988. “[Reagan] is a racist, pure and simple.”

Tutu was not afraid to be outspoken about issues that plagued the South African community, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. His speech was heard all around the world, and his ideas continue to resonate with many activists to this very day.

Tutu was not afraid to be outspoken about issues that plagued the South African community, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. His speech was heard all around the world, and his ideas continue to resonate with many activists to this very day.

Dorothea Dwomoh is an Editor-In-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ Dorothea believes that journalism serves as an avenue of truth and she likes that it...