New York City’s Hotel-Turned-Housing For the Homeless

Area residents have clashed over temporary hotel-turned-housing for homeless New Yorkers, but some see a solution through the permanent supportive housing model.

The Lucerne Hotel in the Upper West Side of Manhattan has been the focus of controversy over the past year, serving as a temporary homeless shelter during the Coronavirus pandemic.

Fierce debate across New York City has sparked a conversation on the efficacy, safety, and long-term potential of using hotels to house the homeless, as the Coronavirus pandemic continues to exacerbate homelessness nationwide.

Since March 2020, the Coronavirus pandemic has only worsened an already raging homelessness crisis in the United States. 122,926 people slept in New York City shelters over the course of 2020. New York City also saw a sharp rise in homeless deaths due to the COVID-19, especially with subways off-limits. Many worry that actual numbers far exceed the reports, however, due to limitations in the survey methodology used and restrictions from COVID-19 regulations.

During the peak of the Coronavirus pandemic in April 2020, Mayor Bill de Blasio signed a multi-million dollar emergency contract with the Hotel Association of New York City to place 10,000 homeless people in vacant hotels. By the summer of 2020, 13,000 homeless adults occupied nearly 20% of commercial hotels in New York City.

Some community members from these locations — most notably, from the Upper West Side — have vehemently opposed this form of temporary housing. Citing acts of crime and public disorder, they argue that these temporary shelters cause a decline in neighborhood quality of life.

(Karl Schultz / Flickr)

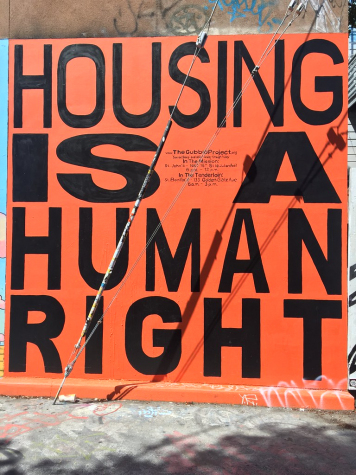

Some disputes have turned aggressive. Advocates for the homeless were “deeply disturbed” by the inflammatory rhetoric pushed by some organizers, asserting that it demonizes shelter residents and contributes to harmful stigma. “Their lives are not disposable, and their needs must be addressed with the same urgency and compassion as those who have housing,” wrote the crowdfunding campaign, Homeless Can’t Stay Home, in a public statement.

With housing being the immediate priority, the De Blasio administration extended the Hotel Association of New York City contract in October 2020, and shelters will continue to play a major role in recovery. However, the release of the COVID-19 vaccine and the approaching mayoral election has turned the focus onto more long-term solutions to address the crisis in the homeless population in New York City.

On February 9th, 2021, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that New York City was on track to provide nearly 300,000 affordable homes by 2026. One of the many projects includes the transformation of a former Jehovah’s Witness Hotel into a 491-unit supportive housing site. The project is headed by Breaking Ground, New York’s largest supportive housing developer.

In the supportive housing model, “about fifty to sixty percent of a building is reserved for people who are exiting homelessness,” Brenda Rosen, CEO of Breaking Ground and a Bronx Science alumna, told me during an interview conducted over Zoom. The rest of the building is reserved for low to moderate-income families or individuals who are chosen through the affordable housing lottery. Aside from receiving permanent housing, residents receive a, “robust set of services including primary medical care, psychiatric care, regular social worker/therapist care, and a host of community-building workshops and activities,” Rosen said.

It is estimated that around 25,000 hotel rooms will not reopen due to COVID-19. “These sorts of buildings could be transformed into a hybrid SRO (single room occupancy) supportive housing model at as little as half the cost of new construction,” said Rosen. The non-profit organization has fully transformed and operated many hotel-turned-supportive housing locations for decades, including the Prince George and the Time Square Residence — the largest supportive residence in the country.

“Whether it is through using hotels or by building new buildings, there is no neighborhood — rich or poor — that we do not encounter some sort of resistance,” said Rosen. Breaking Ground often encourages skeptical neighborhoods to tour the facilities first-hand. “More often than not, if given the opportunity to have frank, candid, open conversations, we build community support.”

The organization expects to fully complete the DUMBO 90 Sands transformation by the first quarter of 2022. Housing, especially the efficacy of supportive housing, will be a major discussion point in the upcoming mayoral race.

“Our goal, whether through new construction or renovation/repositioning, is for anyone to walk by our building and think that it’s just like any other market-rate building in the neighborhood,” Rosen said.

“Our goal, whether through new construction or renovation/repositioning, is for anyone to walk by our building and think that it’s just like any other market-rate building in the neighborhood,” said Brenda Rosen, CEO of Breaking Ground.

Marian Caballo is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey,’ and she is elated to be on staff for a second year. She is drawn to journalism because it...