The Problem of Brexit

Boris Johnson was re-elected Prime Minister to the UK in a landslide election in December. Can he keep the promises that got him there?

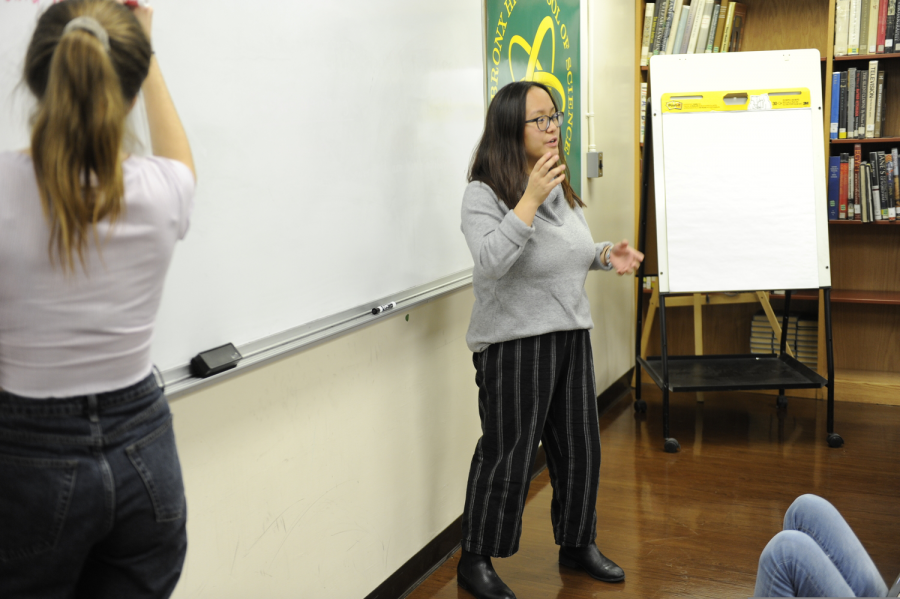

Tenzin Dadak ’21 believes that the UK’s electoral system is flawed because “it allows for the party that wins the most seats, rather than the most votes, to hold power. The single-member district system rewards parties that have concentrated regional support instead of parties who have support spread across the nation.”

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson campaigned on “Getting Brexit Done.” On December 12th, 2019, the UK public overwhelmingly voted to give Johnson the mandate to do this.

Since the 2016 referendum on Brexit, Boris Johnson has been a staple of British politics. He first burst onto the national political scene after being elected mayor of London in 2008, a position he held until 2016. As mayor, he became famous for his frequent gaffes and unreserved personality, often appearing on talk shows and even taking part in an infamous publicity stunt in the 2012 Olympics where he ziplined across London.

According to polling firm YouGov, only 35% of British citizens approve of Johnson, whereas 47% disapprove. These disapproval ratings may be the result of a series of controversies involving Johnson, including his extramarital affair with a journalist, his claim that President Barack Obama may have been born in Kenya, and his statement to a Libyan politician that a city in Libya could be like Dubai if it “clears all the dead bodies away.” These scandals and stories have contributed to his divisive reputation in the political scene, earning him praise from some who claim he is refreshingly honest and entertaining, but scorn from others who condemn his rashness.

Johnson rose to prominence as one of the most fervent supporters of Brexit and the face of the Leave Campaign. He is more polarizing and controversial than almost any other politician in the country, and is frequently compared to President Donald Trump for his nationalistic and often offensive rhetoric. During Brexit, he paid for advertisements to be plastered on London buses claiming that the UK paid the EU 350 million pounds every week, a dubious number that even other pro-Brexit advocates criticized for misrepresenting the EU-UK relationship. After the Brexit referendum, Johnson was appointed Foreign Secretary, but resigned in under two years out of frustration that the UK had not officially left the European Union. After the resignation of Prime Minister Theresa May in July 2019, Johnson became leader of the Conservatives and was elected Prime Minister.

So, if he is so divisive and offensive, how did Johnson win, and by so much?

Many have argued that he benefited from the structure of UK politics. The most recent polls leading up to the election predicted his Conservative Party to win a small majority in Parliament. Instead, they won a massive one, taking a 78-seat lead over the Labour Party. This result has reignited a debate among Johnson’s critics over the legitimacy and effectiveness of the UK’s electoral system.

The UK uses “first-past-the-post” voting, which gives Parliamentary seats to the candidate who receives a plurality of votes in a district, rather than a majority. This means that in districts where there were more anti-Brexit voters, votes may have been split between multiple anti-Brexit parties, allowing for pro-Brexit candidates to win.

Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University explains that there were eleven parties in the general election, eight of which supported a second referendum on Brexit, and the other three of which were pro-Brexit. The eight parties advocating for a second referendum received 52.2% of the vote, whereas the three pro-Brexit parties received a close 46.4% of the vote. However, because the UK electoral system is district-by-district, and plurality-based rather than majority-based, these anti-Brexit parties still came up short in many districts. Sachs argues that if votes were nationalized, Johnson’s party would not have been triumphant, since parties advocating for a second referendum received a larger vote share in general.

Tenzin Dadak ’21 agrees, saying that first-past-the-post voting “allows for the party that wins the most seats, rather than the most votes, to hold power. The single-member district system rewards parties that have concentrated regional support instead of parties who have support spread across the nation.” According to Tenzin and Johnson’s adversaries in the UK, the electoral system could make it dangerously easy for the makeup of Parliament to misrepresent the general will of voters. The UK’s electoral system has been accused of enabling the rise of Johnson and his Conservative Party, allowing for Brexit to become a reality in a country that may regret its 2016 decision to leave.

To his credit, Johnson also ran a smart campaign that catered to the desires of his constituents. Despite his divisive persona, Johnson succeeded in rallying British citizens around his promise to end uncertainty over the fate of Brexit. Leaving the EU was the central issue in the December elections, with an Ipsos poll finding that over 63% of citizens believed that relations with the EU was one of the most important issues facing Britain. In the face of years of fruitless debate over how Brexit would materialize, and after previous proposals by PM Theresa May had been voted down in Parliament or destroyed in the press, Johnson seemed to finally offer a path to Brexit.

Now that Johnson has been re-elected, he has promised to usher in a successful, peaceful Brexit and has repeatedly assured voters that the UK will leave the EU by January 31st, 2020. His proposed deal for leaving aims to maintain the current trade standards between the UK and the EU until December 2020. By December 2020, Johnson claims he will have a new trade deal approved. This promise of bringing change, compromise, and clarity to Brexit was one of the key factors behind Johnson’s re-election.

But this promised future is far from certain, and it has made Johnson the subject of frequent criticism from his political opponents. He vows to have a new trade deal drafted and approved in the short period before December 2020, a claim that has made many Brits wary given the difficulty of negotiating a deal that satisfies the opposite agendas of the EU and UK.

EU official Michael Barnie told the Financial Times that Johnson has allotted an “exceptionally short” time for this trade deal to materialize.Johnson’s demands are high, including autonomy over migration policy and full access to the EU market. The EU may resist these goals, since it wants compensation in return for Brexit. While Johnson has repeatedly assured voters that he would get the deal done by December 2020, the improbable nature of this promise means the period for a Brexit deal could be extended to December 2022. Just last year, he reversed his promise that the UK would leave by October 31st at the latest and instead extended the deadline to its current status of January 31st. It would hardly be surprising if Johnson fails to get a deal approved once again and is forced to re-extend the negotiating period.

What will come of Brexit still remains to be seen, despite Johnson’s repeated claims that he will finally “get it done” for the UK public. Whether he can uphold these difficult goals is unclear, raising the questions of if, when, and how Brexit will occur. With Johnson’s re-election, Britain’s future hangs in the balance.

The single-member district system rewards parties that have concentrated regional support instead of parties who have support spread across the nation.

Kate Reynolds is currently an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey,’ and was a Groups Editor for 'The Observatory' yearbook during the 2019-2020...

Benjamin Oestericher is a Senior Staff Reporter for ‘The Science Survey’ and an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Observatory.’ This is his secord year...