“We did not burn the South Bronx, we were the ones who saved it, ” said filmmaker Vivian Vasquez.

Imagine walking down the street, navigating the remnants of numerous buildings, stores, and homes. Imagine taking a deep breath, and instead of conditioning fresh air, you’re bombarded with the smell of fumes and ash. You may think you’re in a war zone in Syria as the Civil War rages on, or in Kiev as missiles rain down and inflict torment on civilians. But you’re not. You’re in a place tens of thousands of people have called home for decades. You’re in a place that was once the melting pot of New York city, where people of different ethnic backgrounds lived together in harmony. You are in the South Bronx.

Throughout the 1970s, the South Bronx burned to the ground. Fires raged constantly, killing hundreds and displacing thousands. However, these weren’t the seasonal wildfires that often ravage large parts of California and Canada. The fires that brought the Bronx to its knees were the results of political malpractice, corporate neglect, and systemic racism in New York City. There is no one specific moment we can point to and designate it as the beginning of a chain reaction that would cause irreparable damage to the South Bronx community.

The story starts after World War II. During the early 1950s, hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans migrated to the Northeast in search of a better life. The causes of the sudden influx were the economic depression on the island and the newfound affordability of air travel. Puerto Ricans began the first large-scale airborne migration in human history. They arrived in New York City, but were greeted by the overwhelming sight of an overcrowded lower Manhattan. Therefore, they went up the East River and settled in the South Bronx.

At this time, the South Bronx was one of the most diverse communities in the country. The Irish, Jews, Italians, African Americans, and Hispanics all lived in harmony. The neighborhood was alive and kicking, and the post-war neighborhoods of Parkchester and Co-op City promised new housing, fit with modern amenities. If you were walking down the street, you would see children playing in the water of a fire hydrant, or overhear the sound of Hispanic Salsa and Irish Folk music.

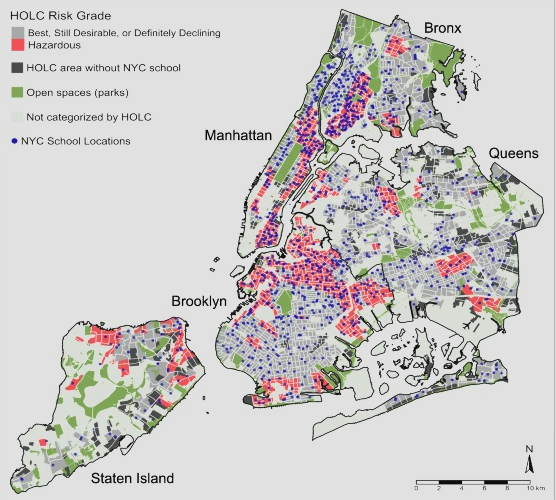

America was entering the “Roaring Fifties,” a period of unprecedented national and per capita GDP growth. Televisions were entering homes, and overall homeownership was rising, and the poverty rates were the lowest in history. However, in the South Bronx, the future didn’t appear as bright. Corporations had begun the process of redlining, where they would draw red lines around certain neighborhoods deemed “high risk.” Investors, bankers, and politicians stopped investing in these communities, resulting in the slow decay of the multicultural paradise.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, the diversity of the neighborhood was eradicated. The White Flight from the Bronx began, as large portions of white residents were able to receive loans from bankers to buy houses in nearby suburbs. Puerto Rican and Black residents, however, were not eligible for these loans. Federal housing agencies, insurance companies, and banks would draw redlines around any neighborhood with more than 10% African and Puerto Rican populations. These minorities were stuck in a declining section of the city, declining at the hands of corporate interest.

The crisis worsened with the beginning of urban renewal. The city decimated the affordable housing in lower Manhattan, looking to modernize the city. However, in the process, approximately 100,000 people were displaced. These people and their families were forced to flee to the crumbling neighborhoods of the South Bronx. Hundreds of thousands of Black and Hispanic New Yorkers were thrust into the worst housing in the city, in neighborhoods where bankers refused to invest.

Then…the fires began.

In 1968,fires increased by over fifty percent from the previous year. Fires became a norm in the Bronx, a part of everyone’s life. Families went to sleep during the brutal cold of the winter months, wondering if they would wake up at all the next morning. Throughout the next decade, 80% of the housing in this area was destroyed and over 250,000 people lost their homes. Despite the desperate situation in the Bronx, local media coverage did little to alleviate the struggles.

The New York City media painted the fires as the fault of the residents, as if they desired their homes to be set ablaze. In an infamous interview, a reporter insinuated that maybe there was “something wrong” with the residents of the South Bronx. As grassroots activist groups such as the New Lords and Black Panthers tried bringing attention to the root cause of the fires, the media painted them as “out of control.” So, with the world around them burning and no help coming, the young residents of the South Bronx turned to something else for protection: gangs.

Gangs became a norm during this time period, a cultural element of the Bronx that has not disappeared. Gangs such as the Latin Lords became a source of protection, purpose, and a desperate attempt at prosperity. As the fires and economic situation tore families apart, gangs provided a sense of community, especially among younger residents. However, gangs also worsened the crisis. The fires resulted in property value plummeting, meaning landlords would hire gangs to burn their buildings and then jack the insurance company. In fact, by 1974, insurance companies issued 10 million dollars in fire damage, and by the end of the decade, it was over 45 million. Residents suffered.

Throughout the 1970s, the fires worsened. Thousands of housing units were gone and people were losing their homes; it was complete chaos. Media coverage was not focused on the government or corporate mismanagement and neglect that caused the fires, but rather on the kids setting the buildings ablaze. Interestingly enough, there was close to zero mention of the landlords who paid these kids to light the fires. According to the media, the fires weren’t a disaster perpetuated by governmental malpractice, but rather an illustration of the inferiority of the Black and Puerto Rican races, a complete falsehood.

Meanwhile, New York City entered bankruptcy. A worldwide oil crisis, caused by geopolitical factors in West Asia, led to a global recession. Investors pulled money from the city, and within a short period of time, New York City transitioned from an era of prosperity to one of financial crisis. To help alleviate the economic woes, the New York City Mayor hired the RAND Corporation. They were to manage the city’s economy and figure out ways to save money. Naturally, RAND looked towards the city’s surplus of fire companies and mandated several shutdowns. However, the majority of the fire companies that closed were in the South Bronx, while the area was being wrecked by the fires. This decision makes no sense, if you evaluate the decision from the perspective of caring for all citizens. RAND did not have this mind.

As the seventies came to a close, the Bronx was decimated. In a PBS documentary film ‘Decade of Fire’ about the fires in the South Bronx, filmmaker Vivian Vasquez said, “It’s hard to accept that they [the fires] could have happened and that it did happen.” Many of us take for granted the luxury of going to sleep in a cozy bed at night, in a warm home, surrounded by people we love. We take for granted the ability to admire the beauties of our neighborhood, whether they are natural or man-made. While we may take a stroll at night and admire the beauty of a sunset, Bronx residents during the 1970s were constantly reminded that their homes had been turned to ash. It became clear that no one was coming to save them. The government and corporate elites neglected them, so if the Bronx were to rise from the ashes, it would have to be spearheaded by the South Bronx community. And that’s exactly what they did.

It all started with the “Stop Fort Apache Movement.” Fort Apache was a movie starring Paul Newman that depicted a conflicted police officer working in a neighborhood plagued by drugs, crimes, and poverty. Fort Apache was filmed in the South Bronx during the worst of the fires, and the negative portrayal of African Americans and Puerto Ricans created hostility toward the movie. Residents and activists of the South Bronx felt Hollywood was profiting off their suffering. The movie’s release sparked mass protests, which were unsuccessful as the movie grossed 65 million dollars. Despite the failure, this movement represented a turning point where South Bronx residents began fighting for the success and respect of their home.

This fighting spirit can be summarized in three words: Stay. Fight. Build. Puerto Rican and African American residents understood it was up to them to save their home. “Stay. Fight. Build” became a slogan to empower residents to build up their community and resist government and economic policies that held them back. BronxWorks (at the time named Citizens Advice Bureau) was established in 1972. They were able to establish aid outreach programs, help those suffering from domestic violence, and much more. The New Settlement Company was founded in 1980 and helped rebuild Bronx housing.

Majora Carter, Bronx Science Class of 1984, was also one of the major pioneers of this movement. She began the “Green For All initiative,” which helped leverage a $10,000 grant into the creation of The Hunts Point Riverside Park, a major step in redefining The Bronx beyond the fires. Green Space became more accessible, and the wreckage of the fires was finally cleared. Her efforts to rebuild the Bronx earned her the Peabody Award.

When it was said and done, the Bronx recovered, but not completely. It’s a serious question to ask if the borough of the Bronx will ever truly recover. Fifteen years of government mismanagement and neglect was all it took to damage a vibrant community beyond repair. As of 2022, 28% of Bronx residents live below the poverty line and the median household income of the borough is a mere $45,000, both statistics being the worst in the city.

Yet, the Bronx community continues to fight. I know dozens of brilliant young Bronx minds who are passionate about their community and want it to succeed. Let us never forget the South Bronx fires. Let us remember that in the face of fire and ash, Bronx residents fought for their community. If the government invests and gives these people a chance, they can build beautiful things.

The documentary filmmaker Vivian Vasquez said, “It’s hard to accept that they [the fires] could have happened and that it did happen.”