This article is one of the winning submissions from the New York Post Scholars Contest, presented by Command Education.

“Lunch is for the weak.”

That is what one Bronx Science mom says when trying to capture the high school’s rigorous, sometimes cutthroat nature. Bronx Science is the kind of school where students vie to see who can rack up the most advanced placement classes (APs) and, in the process, fill their schedules to the brim.

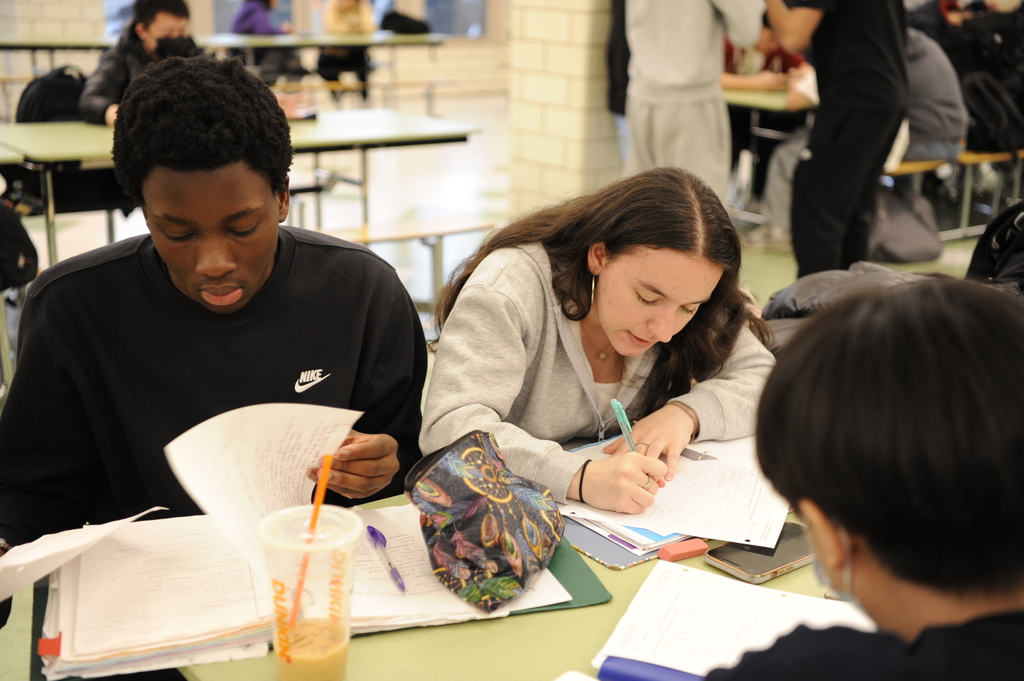

The competition is so fierce that this school year 399 Bronx Science students – roughly 13 percent of the student body – chose to forgo their lunch period each day to take an extra class.

Most of these lunch forfeiters are sophomores and juniors. Some of them capitalize on the extra 40 minutes to take electives, such as journalism or concert band. Others load up on APs.

Giving up lunch means not having an open period between 10:20 and 1:24 five days a week. Some of these students may carve out a free period later in the day, but others will be in class continuously for nine periods, from 8:06 to 2:56, every day for the entire year.

Students believe that taking more classes than required will give them a competitive edge, helping them stand out in a pool of highly credentialed college applicants. They may be onto something.

Guidance counselors, when writing college letters on behalf of their students, are asked to rank the difficulty of a student’s program compared to their peers. The junior who takes that extra AP science class instead of relaxing in the cafeteria may come across as more driven or intellectually curious.

Abby Siegel, an independent college admissions counselor has advised high school students on choosing their courses for over 20 years. “I have never seen a school where the secondary school curriculum is not checked as very important,” she said. “Suppose Bronx Science offers 28 AP classes, and you’re looking at highly selective schools and you’re only taking two. That’s not going to look so great.”

Bronx Science makes it easy for students to binge on challenging courses. The school offers 28 AP classes as well as an extensive “post-AP curriculum,” meaning courses available only to those who have already completed an “entry-level” AP in the same subject.

Since such courses are often taken in addition to standard requirements like English, Math, and History, it is only because of the 399 lunch-skippers that the school can offer some of these heavy-lift specialized classes like neuroscience, microbiology, forensics, and astronomy, as well as electives like race and gender, songwriting, green engineering, and graphic novel analysis.

Many students profess they are glad they chose to skip lunch to take a more demanding schedule. Nika Pekarsky ’25 dropped her lunch period in her sophomore year to take AP Statistics. “I wanted to get started as soon as possible,” she said. “I liked the rigor.” She plans to take an even more advanced class, financial and actuarial mathematics, in her senior year.

Others give lunch a pass in favor of extracurriculars. At Bronx Science, student government, debate-team “leadership,” yearbook, and several other activities also take up daily class periods. These classes, too, can enhance a college applicant’s profile, usually without the extra homework, quizzes, exams, and stress that come with a traditional class.

Isabella Randall ’25 dropped her lunch as a sophomore to play oboe for the concert band, an elective she wouldn’t otherwise have had time for in tenth grade. “I wanted to have a class that I took four years in a row to show colleges my commitment to something,” she said. “They like it when you stick with an activity.”

In terms of classes and extracurriculars, “If you have a couple of things that you’re invested in, and you have leadership in those areas, and you’ve been doing them for several years, I think colleges appreciate that more than just dabbling here and there with no real commitment to anything.” Siegel said.

Many Bronx Science students, however, reject the idea that attending a top college requires forsaking a break for a sandwich and a conversation with friends. Annika Richard ’24, a senior, has taken 10 AP classes over the past four years without ever sacrificing lunch. “I think that having a lunch period has helped me to perform better in my classes. Having a period to mentally break off and then also, if I need to study for a test, I can study during lunch,” she said. She has been accepted to the University of Pennsylvania for next year.

For underclassmen who are considering dropping lunch in future years, Richard said, “I would say if there’s any way to not drop lunch, I would do that. I’m promising one extra difficult class probably won’t set you that far apart in college applications.”

Guidance counselors advise students to drop lunch only after careful consideration. Mr. Nasser, the Assistant Principal of the school’s Guidance Department, says that late-winter meetings between students and counselors (a mandatory start to the college process for juniors) are an important part of the decision-making. The counselors, “give the student and their family the intel to make the most informed decision. The counselor wants to balance stress, expectations, and rigor. They want to make sure that the students are not over-subscribing themselves but also make sure they’re not under-subscribing themselves,” he said. “That’s why it’s a conversation, a collaboration.”

In May, after students finalize their course selection, the school requires those who want to drop lunch to fill out a Google form alongside their parents, who must confirm they are aware and approve of the student’s course program.

Lunch skipping has its skeptics. Nava Litt ’25 has dropped lunch for the past two years and thinks the policy should be abolished. “Dropping lunch has allowed me to take classes and be engaged in a level of academic rigor that I otherwise would not have had,” she said. “Yet, it shows to me that the school is not putting safeguards to prioritize the social and emotional well-being of the students to a level it probably should be.”

Some teachers and parents argue that for high schoolers, lunch is a time to chat, socialize, and blow off steam. At Bronx Science, students may leave the building to get lunch from food trucks or walk to the nearby Starbucks, Dunkin’ Donuts, pizzerias, or bodegas. Getting off campus for a short break each day can be restorative.

There is also the problem of running out of steam. Most Bronx Science students are commuters who wake up in the early morning and face long commutes. Activities fill their afternoons and homework their nights. “A car that’s going 90 miles an hour the whole time, may get to the destination faster, but may not have that stamina or longevity to make it,” Nasser said.

Skipping lunch can make students feel hungry, tired, or hazy. For those who care about their grades, fatigue can drop GPAs just as difficult tests can and students may be depriving themselves of needed nutrition.

Health concerns are a major criticism of the policy. Laurie Cullicott is a nutritionist who specializes in adolescents and athletes. “If teenagers don’t take in adequate calories and nutrients, they can experience health complications like stunted growth, delayed puberty, menstrual irregularities, fatigue,” she said. “All of these issues can negatively affect mood, energy levels, and academic performance.”

Jamie Kubiak teaches AP Chemistry, a double-period class every day. Kubiak notices the toll on some of his students who drop lunch. “If you just skip lunch completely and don’t eat anything, that’s probably not going to help you as much as you’d probably think,” Kubiak said. “Your brain needs food.”

Yet because dropping lunch is common, most teachers accommodate their student’s nutritional needs and allow students to eat in class, knowing that this might be the only time for them to fuel up throughout the day.

“I see people eating Popeyes chicken, sandwiches, pasta, halal, anything,” said junior Mackenzie Finch ’25. The only places where food is off limits seem to be science labs, where there may be toxic chemicals, or computer rooms with expensive equipment.

Administrators try to help, too. Students are usually able to stop by the cafeteria between classes to pick up a tray and may be permitted to skip the lengthy lunch line if needed.

Alexandra Blee ’25 dropped her lunch this year but never goes hungry. “Every day since the beginning of the year, I have brought a sandwich to my AP US history class 6th period,” she said. “My teacher asks me every day about my lunch, which I think is nice. It builds a personal connection.” Not all teachers permit food, but chances are the lunch-skipping student will have at least one or two instructors who don’t mind it.

The key, according to some students and teachers, is having a plan. “Food and lunch is so important that I think getting rid of your lunch if you don’t have an actual plan to eat food is not a great idea,” said Kubiak.

According to Mr. Nasser, Ms. Hoyle, the Principal, said she encourages all students to have lunch. Yet pressure from peers and parents to get into college may sway students in the other direction.

In its tolerance for forfeiting lunch, Bronx Science is unusual. At other competitive high schools, students reported that after the COVID-19 pandemic, skipping lunch was forbidden, to prioritize student mental health and decrease peer pressure. “I have seen students make a lot of decisions that are detrimental to their mental health because they feel like the academics are worth it,” said Khush Wadhwa ’24, a senior at Stuyvesant High School. “If you make it mandatory that you have to care for yourself a little bit, the kids will actually listen.”

Many students don’t wish to drop lunch, but if it is an option, they feel pressure to do so. Litt said, “The administrators at the school should know that Bronx Science students will push themselves. By giving the option, you are inherently pressuring students who want to perform well. I feel I can’t compete on the level of my classmates if I don’t drop lunch.”

Proponents of the drop-lunch policy view it as an exercise in student independence, allowing kids to make their own decisions, pursue the topics they are interested in, and challenge themselves.

Pekarsky, although acknowledging the missed midday break and the stress of another rigorous class, stood by the policy. “Dropping lunch is an undertaking that students should understand, but also still be allowed to do,” she said. “I wouldn’t go back and not have dropped lunch. I feel like I’m more set up and prepared for junior year.”

Ultimately, that is the perspective of Bronx Science. “The student and the family have the autonomy to make the decision that they feel is best for them,” said Nasser – even if that means a few hundred students are going to be snacking on cheese sticks in the hallways, unwrapping bagels in English class, or wolfing down Popeyes chicken during AP Chemistry.

“The student and the family have the autonomy to make the decision that they feel is best for them,” said Mr. Nasser, Assistant Principal of Guidance.