In today’s bustling digital age, journalism has become more dynamic and influential in our world than ever before. From the early days of metal inscriptions to the current spread of fake news on social media, journalism has played a fundamental role in our society. With the emergence of social media and AI technologies, one fundamental question has emerged: What does the future of journalism look like? To answer this, one must explore the past and how journalism has changed over time.

From Chatter to Ceramics: Early Civilizations

The Australian historian Keith Windschuttle once said, “The origins of journalism lie in exactly the same place as the origins of history.” Since the beginning of time, word of mouth has been the way to share information. From tribe to tribe, village to village, and neighbor to neighbor, societies around the world relied on oral communication. Messengers memorized messages and traveled long distances to relay necessary information.

It wasn’t until approximately 3400 B.C.E. that news began to be transmitted through hieroglyphic inscriptions in clay. Ancient Greek historian Thucydides is widely known to be the first journalist, dating back to 400 B.C.E. Ancient Rome’s Acta Diurna, roughly translated to “Daily Acts” is often considered to be the earliest form of newsletter. Created around 59 B.C.E., the gazettes were inscribed in stone or metal and displayed in public places for news consumption. These handwritten reports set journalism on the path to becoming how we know it today.

News Goes Wide: The Printing Press

However, the development of the printing press in 1440 revolutionized the means of communication. Before its development, books and documents were painstakingly copied by hand, restricting their availability. The limited media prior to then often was solely for the wealthy, leaving the poor without access to news.

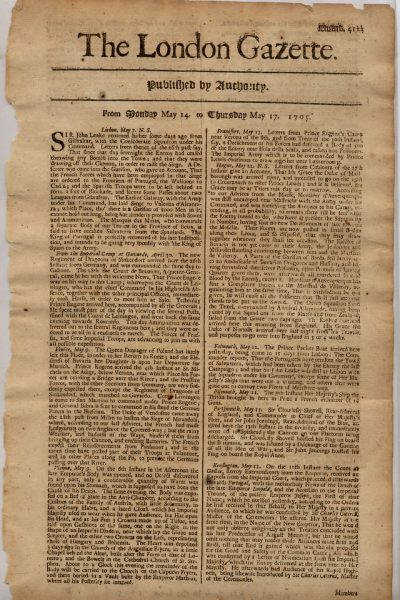

Developed by Johannes Gutenberg, the printing press allowed for the mass production of writing, making news more widely accessible to the public. As a result, newspapers became a popular means of conveying news, opinions, and information to a broader audience. This marked the beginning of regular, periodical print publications. The Relation in Germany, established in 1609, was one of the earliest newspapers and primarily reported on events from various parts of the world.

Credibility Comes to the News: The Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment, spanning the 17th and 18th centuries, championed reason and critical thinking. This influenced journalism by promoting a more analytical and evidence-based approach to reporting. Journalists began to emphasize the importance of presenting facts and reasoned arguments.

The Enlightenment saw the rise of periodicals and journals that focused on intellectual discussions, scientific advancements, and cultural developments. Journalism became a crucial force in the public sphere, facilitating the exchange of ideas and information, and contributing to the development of democratic ideals. Enlightenment ideas, particularly those related to individual liberties and freedom of expression, would eventually go on to make major contributions to the development of the freedom of the press.

Stirring Things Up: The American Revolution

During the American Revolution, journalism played a multifaceted role in informing, mobilizing, and inspiring the British colonists. Political cartoons and illustrations were employed to satirize British policies and leaders. Thomas Paine’s ‘Common Sense’ was a pamphlet that argued for American independence. Published in many newspapers, it successfully reached a broad audience and led to an increase in American resistance.

Influential editors, such as Samuel Adams, utilized their newspapers as a way to advocate for colonial rights and independence. Newspapers were instrumental in publicizing grievances against British policies, such as the Stamp Act and the Intolerable Acts. Journalism ultimately helped crystallize a sense of injustice that fueled the American Revolution.

A New Framework For a New Nation: The Post-Revolution Period

Following the end of the American Revolution, journalism continued to play a vital role in shaping the new nation. The post-Revolution period saw an increase in the number of newspapers and the expansion of circulation. The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, advocating for the ratification of the Constitution, were published in newspapers. To this day, newspapers remain a staple of American democracy.

Newspapers quickly became closely associated with political parties, acting as mouthpieces for Federalists or Anti-Federalists. Partisan newspapers, such as Thomas Jefferson’s National Gazette, disseminated political ideologies and debated issues like the ratification of the Constitution. Ultimately, journalism was cemented into the foundation of the nation through the First Amendment, as the right to a free press revolutionized future society.

Journalism Goes Live: The Broadcast Era

The 34th presidential election day, which took place on November 2nd, 1920, kickstarted an era of broadcast news consumption. As the first election following the end of World War I and the recent ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the radio station KDKA became the first licensed commercial radio station to produce a news program. NBC began broadcasts in November 1926, with CBS entering production on September 25th, 1927.

In March of 1940, journalism took on a new form: television broadcasts. NBC’s Lowell Thomas hosted the first-ever, regularly scheduled news broadcast on American television. Seven years later, at age 54, Dorothy Fuldheim became the first woman in the United States to anchor a television news broadcast, ultimately gaining the title of “First Lady of Television News.”

As the role of television technology in the 1950s became increasingly prominent, so did news broadcasts. NBC ultimately became known as television’s “champion of news coverage.” It became evident that television news was here to stay.

Digging for the Truth: The Era of Investigative Journalism

It is often said that the press is the “fourth branch” of government. The press takes on the responsibility to provide information to help form public opinion. When potential bad acts by corporations or individuals occur, the press ensures that it is truthfully revealed to the public. Despite dating back to the 18th century, investigative journalism, also known as watchdog journalism, gained immense prominence during the mid-1900s.

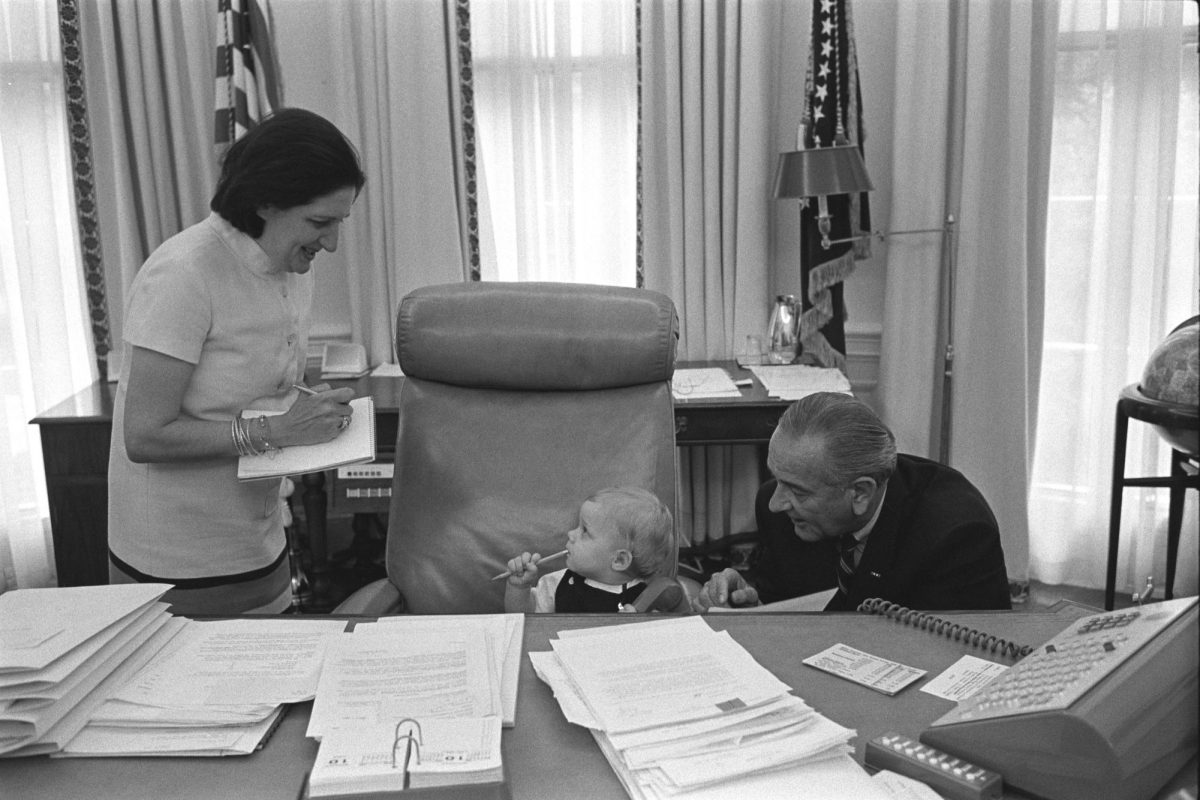

The concept that the press should act as a check on power gained traction and led to the challenging of traditional authorities, including religious and political institutions. These journalists, known as muckrakers, sought to uncover corruption and abuses of power largely due to the Freedom of Information Act.

Passed in 1967, the Freedom of Information Act allowed the public to request access to the records of the executive branch of the U.S. Government. To modern-day journalists, the ability to access documents serves as an essential tool. According to The New York Times, “Times journalists file requests every day in search of documents ranging from emails sent by top bureaucrats to records about Taser use in a particular police department. Open records laws play an important role in the work of reporters day to day.” By emphasizing the First Amendment, the act has been vital to the development of investigative journalism.

The most notable example of investigative journalism was the Watergate scandal. The Watergate affair emerged as a significant political crisis in the United States at the beginning of the 1970s. Five men connected to President Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign were arrested for a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters on June 17th, 1972. Investigations revealed that the Nixon administration attempted to cover up its involvement in the break-in by destroying evidence.

Nixon ultimately resigned on August 8th, 1974, becoming the only U.S. president in history to do so. Through the work of Washington Post journalists, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, the Watergate scandal remains a landmark example of the power of investigative journalism in uncovering abuses of power and holding the government accountable.

Journalism Redefined: The Digital Era

The foundation of democracy is the ready availability of reliable information. ‘We the people’ rely on being informed. Our democratic system is based on the fundamental principle of the vote – an informed vote. With the World Wide Web’s opening to the public in 1991, journalism was revolutionized, allowing information to be accessed quicker than ever before.

Suddenly, journalism was no longer confined to geographical borders. Through the migration to digital platforms, news was globalized at the fingertips of the public. Although the world’s first 24-hour television news network (CNN) made its debut on June 1st, 1980, the introduction of the web immensely contributed to the acceleration of the news cycle. Networks could release breaking news updates as soon as new information became available. Additionally, the introduction of social media platforms in the early 2000s, such as Facebook and Instagram, promoted citizens to become active participants in journalism by sharing events and opinions.

However, this did not come without a cost. With the rapid dissemination of information and the ability for anyone to publish, journalistic standards began to fall. As fake news began to ravish the media, the power of journalism came into question. The prevalence of misinformation on social media has eroded trust in traditional journalism.

The impact of social media on journalism is complex and multifaceted. Nevertheless, the digital age has undoubtedly offered immense benefits to the future of journalism.

From the modest beginnings of messengers in ancient times to the vast reach of digital platforms, journalism’s rich history reflects the complexities of societal evolution. In light of an uncertain and constantly changing future, the lessons from journalism’s past offer priceless insights into the role that the industry must play going forward.

“Journalism can never be silent: that is its greatest virtue and its greatest fault. It must speak, and speak immediately, while the echoes of wonder, the claims of triumph and the signs of horror are still in the air,” wrote Henry Anatole Grunwald, an Austrian-born American journalist and diplomat.