“Achievement” has long been a measure of perceived intelligence for students. Doing laudatory work is the standard. Being “gifted” or an “overachiever” has always been seen as inherently positive, as these labels are given as compliments to individuals who do more. Time and time again, the rhetoric of “more is better” manifests itself within students. However, the experiences of high school students are a variety of personal narratives that are more telling of their reality.

Many New York City youths entering a new school year are screened to see if they are “gifted and talented.” The program differs from school to school but, in general, children from 4-7 years old are tested in a room with a proctor, with an exam that picks their brains to see if they make the cut, to live up to the title of “Gifted.”

Fast forward ten or so years. Whatever had taken these students as far as they had gotten has faded away into the gray space of decorated mediocrity. How do they cope?

Angeline Rivera ’26 is a student at the Bronx High School of Science. She is currently the Vice President of the Bronx Science Cheer Club and an event coordinator for the Youth Medical Association. She sat down to speak with me about her experiences as an academically gifted child in early levels of schooling and how this designation has impacted her to this day.

Rivera said, “Regents prep for my school started at 6 A.M. in the mornings, so I’d be at school from 5:50 A.M. onwards, and then I would do regents prep until 7:30 A.M., and then I’d go into school and complete my regular school hours.” It doesn’t end there. She continues, “Even then, after school, I would have Algebra 1 class, which would last until four. So I would be at school from 5:50 A.M. to 4:00 PM and then I would have to go home.” The Regents Exams are New York standardized tests at the high school level. Some middle schools offer advanced courses or prep to allow eigth grade students to take the ninth grade level tests, so those students can enter more advanced classes in high school.

The long hours sound like a good trade-off for better education and probably seemed that way to Angeline in the eighth grade, but when she entered high school, she began to think differently. Speaking in retrospect, she said, “It’s a lot of mental and physical exhaustion.”

Audrey Jing ’26 is a student at Stuyvesant High School. She is an Assistant Captain of the Stuyvesant High School Math Team, President of Stuyvesant’s Future Business Leaders of America (FBLA) chapter, tutor with and leader of the New York City chapter of Math Matters, and was previously a competitive synchronized ice skater. Her take on academics is much different from Angeline’s, but there are certain similarities between the two.

Jing, similarly to Rivera, talked about the high caliber of her early schooling. Jing said, “I was considered ‘gifted’ as a kid, and I think it had both benefits and costs for me.”

She continued, “In terms of benefits, I was able to access advanced classes and discover my interests much earlier, which I think helps me succeed in academics to this day. However, being labeled as a “gifted child” placed a lot of pressure on me to constantly live up to the name, and it made academic success a big part of my self-worth.”

As she elaborates, a much fuller picture is formed. She said, “I try very hard to not define my self-worth in terms of academic success, but I do take a lot of pride in things that I’ve accomplished inside my school. Finding the right balance between acknowledging academics and letting it consume me is very difficult, but I think it’s especially important in a high-pressure school like Stuyvesant.”

Ariana Oliveri ’26 is a student at Bronx Science. She is a member of the Co-ed and Girls Wrestling teams, an active member of the Gardening Club in school, and does wrestling and weight-lifting outside of school. In her free time, she likes to bake and read.

Oliveri elaborates on her experiences with being defined as ‘gifted.’ She said, “I was a gifted kid as a child. I read from an early age. That manifested a very poor work ethic. Like many kids at Bronx Science, I did not have to try very hard during middle school, so now that I do have to try during high school, it’s just very stressful. Because I haven’t developed the work ethic that many people have, I procrastinate a lot.”

Somehow, procrastination and perfectionism go hand in hand. Students have created a paradox where pushing work back while wanting to do it to perfection is realistic.

Alianna Ribadeneira ’25 is a student at Bronx Science. She is the Secretary of the Student Government, a Model UN delegate, and is a regular cast member in many of the school theater productions. She provided her take on how she has been affected by school.

She said “Yeah, I was seen as a gifted kid, as most people at this school were, actually. It definitely led me to be a perfectionist. Ever since I was born, essentially, I was a perfectionist, all through elementary school, and all through middle school. But then when I got into high school, it kind of reversed. This school made me realize you can’t always be perfect. I do think to some extent [school] gave me very high standards for myself. In elementary school and middle school, things came extremely easy to me, and it was mostly just common sense. But now that I’m in these advanced classes, it’s obviously not.”

The consensus surrounding being “gifted” in early education also reflects such thoughts. From a neutral stance, being “gifted” is a doorway to a plethora of resources and opportunities starting from an early age, but it does have its detriments. According to Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child , “The interaction between genetic predispositions and sustained, stress-inducing experiences early in life can lay an unstable foundation for mental health that endures well into the adult years.” The entire article articulates how all factors of the early stages of life, including education, can denote the state of an individual’s mental health in the future.

Similarly to Ribadeneira, Jing had also mentioned issues with her self-worth concerning school. When the others were asked about the same topic, it seemed as if a silent consensus was formed.

Oliveri also connected to the words of the others. “It’s kind of expected that you get above a 95 in all your classes, average-wise. Then you take as many Advanced Placement classes as you can. Well it’s not expected for you to skip lunch, but you shouldn’t be having free periods, you know? Although it’s not exactly said, it’s felt. I think people hear “Specialized High School” and they expect you to be doing everything. Like they expect you to be getting straight As. No one wants to hear ‘I go to a specialized high school and I’ve been getting 85s on my recent tests.’ It’s kind of expected that you are meant to be “effortlessly good.” She provided this as a common experience between students, explaining the unheard but felt parts of a student’s experience.

She then continued, “When you don’t get something and everyone else does, it makes you feel like you’re not that smart, and it’s not that you’re not that smart, you’re just not getting it, you’re just not understanding it. It makes you feel dumb.”

On a more personal note, she said “I’ve definitely gotten better [with tying my self worth to my academics], but it is in a sense, where if you’re not a good student, it just feels like you’re not impressive or important, you’re just o.k.”

Ribadeneira expands on Oliveri’s proposed theme, saying, “Sometimes I attach my value to my grades, because it’s also how a lot of other people at this school determine their value. They determine it by their grades, and even though I want to avoid doing that, it’s difficult because it’s a very stressful and pressuring environment, and it seems like people are trying to compare themselves to you. You hear people saying ‘I have all these extracurriculars ,and I have all of these APs, and I’m doing this and this program outside of school.’” She has addressed how the people around her solidify an academic and non academic standard that she seeks to meet, one that, if she doesn’t meet the standard, makes her feel worse than those around her.

The connection can take many forms, between students and within individuals. Rivera, in particular, spoke a lot about how she connected her individual performance to her emotions. In a blanket statement, she said, “If I got a low grade, I would be very upset. I feel like I was forced…well not forced,but like I had to do good to feel good about myself.”

Unfortunately, their experiences are not uncommon among students nationwide. There have been studies that correlate self-esteem and motivation to academic performance, which denote that self-esteem is major in the ability to perform well in school. Similarly, there is another prevalent concept related to the correlation between self-esteem and academic achievement: Social Comparison Theory. Social Comparison Theory is either the mental process of contrasting the ability of oneself from the ability of others, either lower or higher, or the assimilation of one’s ability to the ability of others. After its proposal by psychologist Leon Festinger in the 1950s, it has been studied and substantiated within school environments.

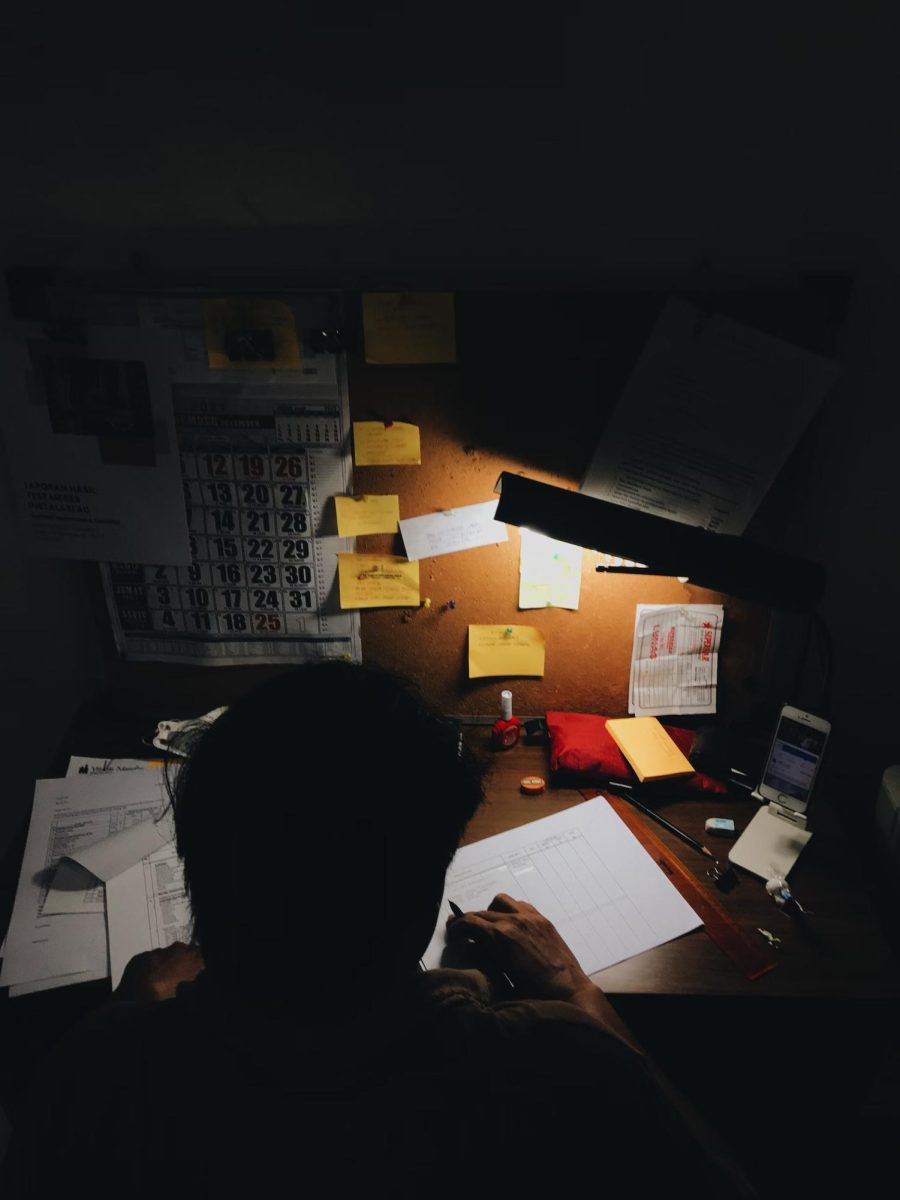

In retrospect, Rivera recognizes the negativity that her mindset perpetuated, but still grapples with her reasoning as to why she did what she did. “This sounds really bad, but if I got a grade that I didn’t like — I wouldn’t deprive myself of free time, but I would force myself to not have free time. Instead of going home and maybe relaxing for an hour, taking a nap, or eating a snack, I would just study as soon as I got home, and I would continue to study until I went to sleep. I would punish myself in a way, thinking that I didn’t do well and that I had to study more. I didn’t allow myself to relax.”

We reflect on the school system as something to benefit our youth. But when the science and the students themselves have concluded that there are changes that should made to schooling nationwide, the question is: why do we wait?