In 2007, the core of Objectivist philosophy was plucked out and put on full display to an entirely new assembly of spectators. After decades of contention between modern philosophers and an undying clash between leftist and right-leaning thinkers, it came as a surprise to millions when the beliefs of Objectivism were the central inspiration of 2007’s Video Game Of The Year ‘Bioshock’.

A monologue from the hyper-capitalist antagonist of the game, Andrew Ryan, perfectly summarizes the Objectivist’s views on selflessness, the injustice of labor, and our inherent duty to lead a life that satisfies all intrinsic desires.

“Is a man not entitled to the sweat of his brow? ‘No!’ says the man in Washington, ‘It belongs to the poor.’ ‘No!’ says the man in the Vatican, ‘It belongs to God.’ ‘No!’ says the man in Moscow, ‘It belongs to everyone.’ I rejected those answers; instead, I chose something different. I chose the impossible. I chose… Rapture. A city where the artist would not fear the censor. Where the scientist would not be bound by petty morality. Where the great would not be constrained by the small!”

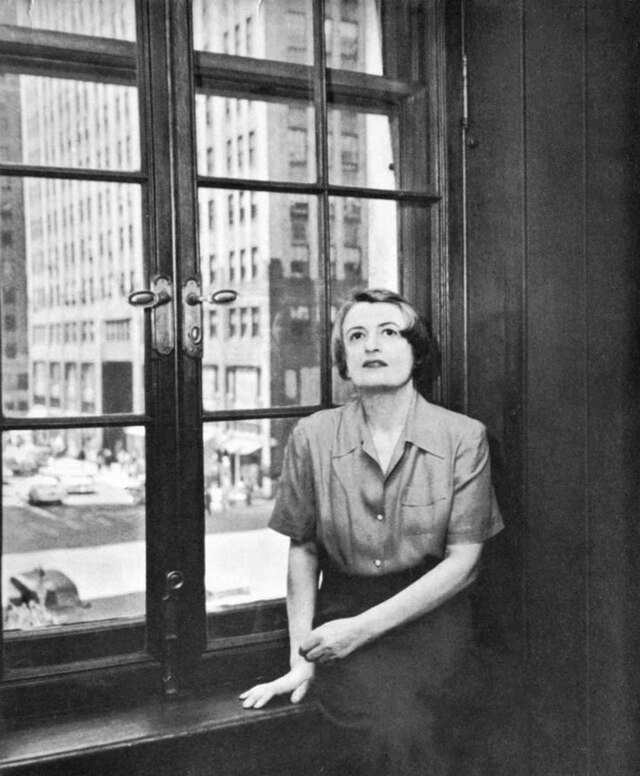

Andrew Ryan himself is a satirical rendition of Russian-American philosopher Ayn Rand (1905-1982), with their shared beliefs of obligation to one’s self-interest and similar-sounding names being far from mere coincidence. Their differences lie in the fact that, while Andrew Ryan serves as a compelling and multifaceted videogame villain, Ayn Rand was a real person, whose belief that there is somehow virtue in acts of utter selfishness has given rise to a generation of money-hungry magnates who believe the world is theirs to conquer, plunging the rest of us into late-stage capitalism.

Alice O’Connor, born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum in 1905, arrived in New York City on February 19th, 1926. With dreams of becoming a screenplay writer, she learned English with the help of her relatives and moved to Hollywood. She met her husband, aspiring actor Frank O’Connor and the two were married by 1929. She decided to adopt ‘Ayn Rand’ as her pen name for her writing.

She and her husband were strong proponents of the 1940 Republican presidential candidate Wendell Wilkie, which inspired their decision to participate as full-time volunteers in his campaign. During the campaign, Rand was struck by the disconnect between Willkie’s publicly stated principles of freedom and limited government and the reality that he sought power through a nationwide government apparatus.

She was fascinated by the strong contradictions between the rhetoric of Western politicians and the means through which they pursue state power. This campaign also introduced her to American figures who argued in the unalterable favor of free market capitalism.

It’s important to note that after immigrating to the U.S., Rand experienced and admired American citizens’ economic dynamism and individual liberties. This admiration was intensified by the fact that she witnessed firsthand the devastation wrought by the socialist policies and lack of economic freedom under the Bolshevik Revolution.

Looking out at all the opportunities and privileges that resulted from more unregulated economic principles, and then surrounding herself with individuals who spoke in strict favor of life under Laissez-Faire Capitalism, it’s no wonder that Ayn Rand would go on to nurture a philosophy that is now defined by such beliefs.

In 1943, her big break had arrived. Her novel, The Fountainhead was a literary success, introducing Ayn Rand to the world as a rugged individualist, tied to a belief in the unapologetic pursuit of one’s own happiness. Before its release, twelve publishers rejected the novel until a single editor at the Bobbs-Merrill Company risked his job to have the manuscript published.

The book centers around an uncompromising modernist architect named Howard Roark, who struggles against a collectivist culture that fails to accept his innovative, individualistic designs. He is pressured to make unorthodox moral choices to uphold his creative vision, refusing to bend to the will of the conformist masses.

The Fountainhead served as the world’s first window into Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism. It is presented as the rejection of all forms of faith and altruism, advocating rational self-interest, individual rights, free market capitalism, and reason as the prime motivators of human ethics and knowledge.

In short, Rand believes that humans are inherently selfish, and we are committing a dire injustice to both ourselves and the world when we abandon our self-interest in favor of collectivism. It isn’t just rational to live with strict regard for your own needs; it is the very purpose of human existence.

With such an unorthodox message for the masses, The Fountainhead was and still is incredibly divisive. W.A. Sinclair of The New York World-Telegram had the following to say regarding both the novel and its author: “Miss Rand has trained herself for something better than the artful cult-making in which The Fountainhead reposes. Her notions of what is noble and what is not, what is courageous and what is contemptible, are, nonetheless, disturbingly naive.”

Unfortunately for those who believed that there was more to life than our own selfish pursuits and that there is internal fulfillment in doing things to help others, Ayn Rand was now under the spotlight. And she would not waste a second with the influence she now held.

Atlas Shrugged, released in 1957, was Rand’s next heavy hitter, now considered her magnum opus. The story depicts the economy of the United States crumbling under increasing government control. The nation’s most brilliant and productive minds across industries – scientists, inventors, artists, businessmen – have mysteriously started disappearing in a coordinated “strike.”

Railroad executive Dagny Taggart seeks to understand the reasons behind their disappearance, eventually encountering John Galt, the strike’s mastermind. Galt has been rallying these strikers to go into hiding in a remote valley called Galt’s Gulch. Their goal is to undermine the corrupt, socialist system by withdrawing the productive genius that drives progress.

As conditions worsen, Galt delivers a climactic speech espousing Rand’s Objectivist philosophy – that the individual must live entirely by their ability and effort, rejecting all forms of sacrifice for others.

The book was an international bestseller, however, it was panned by most intellectuals of the time who believed that the novel was a mess of Rand’s pretentious philosophizing instead of a concise story that could ever contribute to the larger society. These critiques had depressed her and thankfully discouraged her from writing for quite some time.

What she had created with both Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead were moral and philosophical guides for business people, entrepreneurs, and conservatives. These are people who were predisposed to the same selfishness that Rand fights to defend with works that didn’t even fit into the philosophical conversations of their time.

These books serve as mere justifications for selfish behavior instead of catalysts for any prosperous changes to the world we live in.

It can not be said that Ayn Rand’s work does not inspire change, however, as she has managed to convince the John Galts and Howard Roarks of the world that the immense damage they have inflicted on larger society is not only acceptable but that it is a necessary factor to “progress.”

Peter Thiel, the PayPal co-founder and venture capitalist worth over $3 billion has credited Atlas Shrugged as one of the most influential books in his life. His data analytics company Palantir has been working closely with government agencies like ICE on immigration enforcement efforts that concern civil liberties groups.

Elon Musk has referenced Ayn Rand and Atlas Shrugged on multiple instances, even recommending the book, stating that it had inspired many of his fellow entrepreneurs. Musk has repeatedly been criticized for his stance against unionization efforts at Tesla, including allegations of firing employees involved in union activities.

In the 1980s and 90s, Donald Trump spoke positively about Rand’s novels and ideas, particularly her glorification of individualism and competition. He was influenced by her defenses of self-interest and laissez-faire capitalism.

With all the issues we face in contemporary society, from unequal wealth distribution and social immobility to the immense influence of corporations in our political sphere, the last thing we need is more Objectivists like Ayn Rand stomping out efforts of collectivism for the “greater good” of the individual.

The most beautiful facets of life are those that allow us to embrace our selflessness and demonstrate compassion for others. Love, for example, is often expressed in efforts to intertwine or replace our desires with those of another person or group of people. It is not the feeding of selfishness that brings us peace or contentment; instead, it is our willingness to compromise that allows us to change the world in ways that benefit us all while also finding internal satisfaction from the contributions we’ve made to the people we care about.

Teaching is one of the most necessary and noble professions in society. To teach is to dedicate everything you have to the advancement of future generations, acting with complete regard for others in ways that would churn the stomachs of Objectivists. As we dedicate ourselves to similarly noble callings, we find that our “selfishness” has transformed.

Suddenly, our deepest desires do not entail a world that crushes collectivism and community. Suddenly, our selfishness is fed by the comfort of our outstretched hand, pulling our fellow man closer to a world free from egoists like Ayn Rand.

It can not be said that Ayn Rand’s work does not inspire change, however, as she has managed to convince the John Galts and Howard Roarks of the world that the immense damage they have inflicted on larger society is not only acceptable but that it is a necessary factor to “progress.”