“Cinema is a mirror that can change the world.” – Diego Luna

As technology takes over, and books fade further and further into a distant era, movies are bestowed with an even greater power to influence and inspire. When it comes to historical cinema, however, whether it revolves around the harrowing tales of Holocaust survival or deals with the gruesome details of bloody battles, these films have evolved to serve a newly-minted vital purpose – educating the masses.

Sure, academics roll their eyes, and proclaim that films are fantasy and never truly capture real events. They are probably right. But this responsibility is one many directors consider when developing these creative endeavors, and maintaining some semblance of historical accuracy in doing so is an integral component.

Historical films comprise many of Hollywood’s finest pictures, with the likes of All Quiet on the Western Front, Bridge on the River Kwai, and Platoon, all films based on fictionalized renditions of history, winning the Academy Award for Best Picture. Other films are more grounded in reality: 12 Years a Slave, and Patton to name two more Best Picture winners. Both of these subcategories within historical drama, the real and the fictionalized, have some commitment to their source material. The latter of the two – movies that tell real stories of real people – receive an added layer of judgment.

To proclaim that cinema must reflect reality is pretty pompous. And professors and intellectuals who post hour-long videos critiquing movies receive perhaps justifiable judgment (yes, you Ben Shapiro).

Dr. Tim Benbow, a Professor at King’s College in London and expert on Dunkirk, wrote, in his essay discussing the accuracy of Christopher Nolan’s epic Dunkirk, that historians should be wary “in critiquing the work of an entirely different profession.” As he slyly put it, “I suspect it would be rather discomforting for an academic to have a film director sitting in on a lecture and taking notes on one’s performance.”

I, for one, could not agree more. In a perfect world, where people have a general understanding that true stories are seldom entertaining enough to warrant a film and that most adaptations and portrayals are at their very best misleading, these reviews are the stuff of pedants. However, audiences still cannot drill that into their heads. And thus, historical accuracy is important, not just for creative reasons. Hollywood is a center of entertainment and, unfortunately, information. Audiences learn about important people, cataclysmic events, and rousing tales of heroism from the big screen, making a director’s commitment to “getting it right” as important as ever.

Two films in particular, Steven Spielberg’s masterful Schindler’s List and Nolan’s Dunkirk, serve as an excellent case study for historical accuracy in cinema.

In 1993, Spielberg embraced his Jewish roots, consulting dozens of Holocaust survivors and experts to create perhaps his greatest film. He tells the story of Oskar Schindler, a businessman in Nazi Germany whose actions helped save more than a thousand Jewish people held in the concentration camps. His work has been credited as one of the most grotesque portrayals of the camps in movie history; its violence is simple and calculating, short and brief, a representation of the absence of remorse among Nazi officers. Schindler’s List was never billed as a documentary. It isn’t. In fact, the film is based on a novel written about Schinder, meaning it is several layers removed from the actual events that inspired it. However, that distinction has not stopped one of the greatest films of all-time from being subjected to rigorous scrutiny over its accuracy.

Sometimes, these qualms are unmerited. Here, however, Spielberg’s rationale for having written the movie comes into focus. As he discussed at length, one of the motivating factors behind telling this story was the rampant misinformation surrounding the Holocaust.

Holocaust denialism, despite Spielberg’s best wishes, is still alive and well. In fact, disappointingly, a study conducted among Millennials and Generation Z found that 58% of people could not name one concentration camp. However, historians credit his film with reviving a dormant movement insistent on Holocaust education. Intellectuals might fawn over a film actually changing people’s minds about one of history’s most infamous events; still, the truth remains: Schindler’s List informed millions across the globe.

Historians have been quick to address discrepancies and oversimplifications in the story. In fact, Professor David M. Crowe, a leading scholar on Oskar Schindler, has called the film “highly fictionalized” and certain scenes “total bogus.”

The film takes place across three years in World War II, capturing the basics of Schindler’s story. As a German businessman, Schindler benefited from the immoral and exploitative labor provided by Jewish prisoners in the camps. Throughout the war, however, Schindler would attempt to better their conditions in his factory, as the film highlights, and by 1945, he freed more than a thousand Jewish prisoners from the death camps. With the help of Itzhak Stern, portrayed by Ben Kingsley in the film, Schindler constructed a list of individuals he asked to employ; he would free them instead.

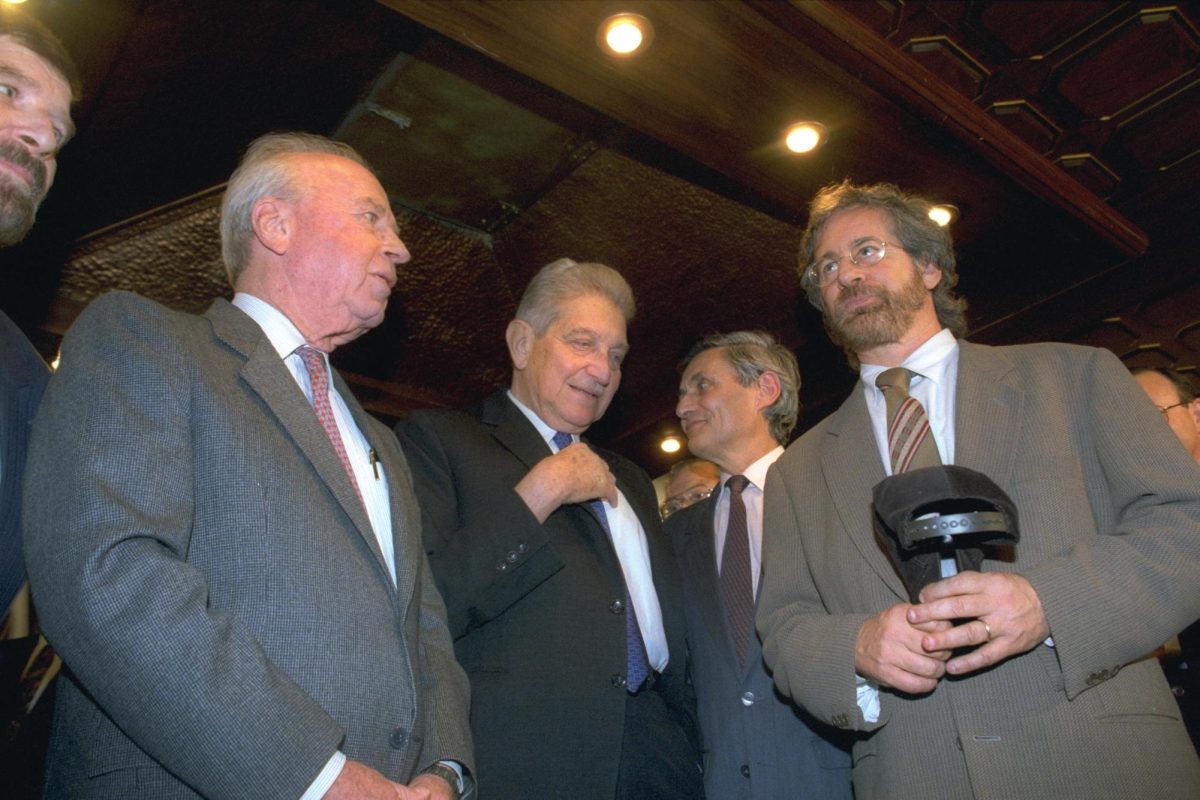

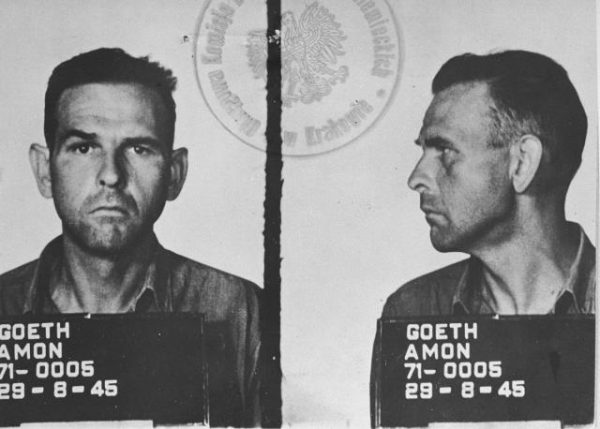

To his credit, Spielberg did not go at it alone. He consulted several Schindlerjuden (individuals who were freed by Schindler), the most potent voice being Poldek Pfefferberg. He also worked alongside Leopold Page, who consulted on the novel Schindler’s Ark which inspired the movie. Ralph Fiennes, who played the Nazi commander of Plaszòw Amon Göth, interviewed Holocaust survivors who interacted with Göth as research for the role. All of this is to say: Spielberg did his homework and the film was well-researched and respected the true history.

That being said, to call the film accurate would be too strong an assertion. Some of the fabrications and inaccuracies are innocuous enough; Spielberg centered the story around one list, when in reality, there were nine written.

Other missing components are more problematic. For example, Itzhak Stern, the Jewish prisoner Schindler tasks with constructing the lists, was really three different people. Stern did in fact play a pivotal role in Schindler’s plan. However, so did Abraham Bankier, a banker who first recommended Schindler take in Jewish laborers to better their conditions, Mietek Pemper, and Marcel Goldberg. In the film, though, Stern is the sole figure assisting Schindler. Omitting these prominent figures definitely simplifies the story, but also leaves a real and complex part of it absent from the film. Furthermore, Schindler himself played a very minor role in writing and selecting people for the list, something Spielberg attributes to the titular character. In fact, as the lists were written up, Schindler was serving a jail sentence for bribing Göth.

The scene depicting Schindler and Stern consulting on the construction of the list was deemed “total bogus” by Crowe.

Two other major inaccuracies jump off the screen: the “Girl in Red” scene, and Schindler’s breakdown at the end of the film. Neither of these happened, and both were Hollywood-esque dramatizations of real events. The former of the two was included as a creative choice by Spielberg, allowing the audience to identify a specific revelatory moment for Schindler. As Crowe observed, this was “totally fictitious,” and took tremendous liberty. Historians, including Crowe, criticized the scene for glamorizing Schindler as more selfless and inspirational than he was. Similarly, the breakdown Neeson portrays as he addresses the Jewish prisoners he had freed, in which he expresses remorse over not having saved more, was exaggerated and never occurred.

Overall, Schindler’s List is a film, not a documentary, and thus, there are several major and minor discrepancies between the true events and Spielberg’s rendition. By Hollywood’s standards, though, it is respectfully accurate. Several scenes have been cited as capturing the gruesome violence and inhumanity of the camps. The real question still remains how accurate these films should be.

There does not seem to be genuine consensus on that matter. Scholars around the globe have debated the ethics of historical films. In fact, The Guardian contributor Sir Simon Jenkins, a prominent British columnist, engaged in one such dispute surrounding the films released in 2018. He deemed Vice, among others, “fake instant history,” criticizing the gross liberties taken with true stories like Cheney’s; Jenkins expressed concern about adaptability, inquiring as to “what a history student is supposed to make of the film.” The response – the script writer encouraged those viewers to “conduct actual historical research.” His argument was fairly simple: films are not documentaries, and students should not look to Hollywood for a history lesson.

That seems simple enough, at least in principle. However, some of these stores play important, maybe oversized, roles in informing the public. As mentioned earlier, part of Spielberg’s motivation behind making Schindler’s List was the growing epidemic of Holocaust denialism and misinformation. When the film won seven Academy Awards, Spielberg spoke candidly about the harrowing stories he examined. He “implore[d] all educators [to] not let the Holocaust remain a footnote in history. Listen to the words, the echoes, the ghosts.”

Even so, some prominent figures including Deborah Lipstadt, the United States’ Envoy for Combating Anti-Semitism, had mixed reactions to the film. She credited its “artistry and beauty,” praising it for “bring[ing] the story to countless people.” However, in her heart, she expressed frustration over the story revolving around Nazis. Schindler and Göth are the center of the story, one’s growth and the other’s fall. Lipstadt worries that the film did not teach the right thing; in fact, it “eased in the phenomenon that the Shoah [Holocaust] is about non-Jews, so there is nothing to learn from it.” That is an opinion. And unfortunately, Holocaust denialism statistics featured above might justify her concerns.

Another prolific picture rife with complaints over its inaccuracies is Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk. The critically-acclaimed success has been debated over, with historians questioning its adherence to the source material, the evacuation of several hundred-thousand British troops off the beaches of France. Benbow lent his thoughts to the controversy surrounding the film. By his observations, Nolan captured much of the emotion and weight of the battle. Sure, there were inaccuracies: “the sea and the sky were remarkably empty which meant that a film that paid such great attention to the visuals did not quite convey the scale of what happened.”

Benbow adds an interesting dimension to this discussion: Dunkirk was a popular event, revered and glorified across modern society. Might that factor into an evaluation of the film?

Theoretically, a film like Dunkirk is not expected to inform people as much as films depicting less reported events. One might argue that it can take more liberties than the average picture surrounding more obscure or less illuminated real-world moments. Still, most scholars would agree that Nolan did a respectable job exploring the ramifications and details of the Allied evacuation without straying too far from the historiography.

Kat Williams, a graduate assistant at the University of Texas – Austin, pursuing a PhD in Rhetoric and Language, was kind enough to answer some questions surrounding the ethics of historical accuracy more broadly. She recently worked alongside Professor Scott R. Stroud on a project entitled Historical Accuracy in Entertainment Media.

In general, the name of the game is “ethical,” in other words, maintaining a morally prudent standard when applying historical events and persons to adapted media. And accordingly, Williams feels, “filmmakers have a duty to make historical films as accurate as possible.”

That requires consultation, something Williams feels is dependent on the type of project a filmmaker is pursuing, notably “the kind of historical event or period being depicted.” As she points out, the breadth of those discussions between directors and witnesses or historians is also dependent on several other factors:

“If the creator is making a historical film about a community or culture that they are not from, I think that kind of situation would call for significantly more consultation than a filmmaker creating something based on their own culture or an autoethnography that they already have intimate knowledge of.”

Williams points out that creators depicting more distant events might have more wiggle room, as there might be a greater responsibility when conveying “more recent events where the subjects are still alive and could potentially face real-world consequences.” Similarly, the nature of the stories portrayed plays a crucial role in determining how accurate it ought to be. Spielberg’s Schindler’s List requires far more attention and care than television shows like The Great, which provide light-hearted renditions of more distant historical figures.

As for historians’ role in addressing these discrepancies, Benbow and Williams agree that not everything needs intense scrutiny. However, she still holds that “in general, historians have a professional responsibility to share their expertise.”

In her project alongside Professor Stroud, one of the central case studies was The Crown, the Emmy-winning drama surrounding the British Royals. This project might have a different duty to fulfill: it depicts living, public figures who often dislike their dramatized counterparts. Might there be more scrutiny associated with the show? The Royals have requested disclaimers be added to episodes as a way of characterizing the show as dramatized and not accurate; Williams thinks that would be harmless: “it seems like a relatively simple fix to help the subjects of the film feel more comfortable.”

Though, for Williams, the essence of history is far more important than the minutia. Williams referenced a Google Gemini incident where the AI chatbot, programmed to avoid stereotypical prejudices, depicted “German soldiers from 1943” as Black and Asian. In that case, Williams feels “the finer details matter significantly to the overall plot, and changing those details would change the entire narrative into something completely different, inaccurate, and offensive.” Overall, however, the nature of events is what pieces of historical media must capture.

As Williams puts it: “a good way to balance accuracy and creativity is to focus on the truth of the forest rather than the trees.” In other words, adding more diverse representation or applying conventional beauty standards to different eras does little harm to the overall picture, so long as the concrete information, the emotion and gravitas, and the stakes are portrayed properly.

As for myself, an aspiring historian, I enjoy historical content for what it is. But I tend to side with Williams: seeing the forest through the trees is essential. In my opinion, films like Schindler’s List accomplish that task tastefully. When it comes down to it, though, filmmakers ought to be cautious with how liberally they depict history.

There is an overplayed quote from philosopher George Santayana, that “those who cannot remember history are condemned to repeat it.” And if Hollywood and the big screen are to play as crucial a role as they presently do in helping everyday people remember history, they better do a good enough job capturing the truth.

Otherwise, these projects might unintentionally bolster an already uninformed populace, something that harkens back to darker times – times these films often depict and times we ought not to repeat.

There does not seem to be genuine consensus on that matter. Scholars around the globe have debated the ethics of historical films. In fact, The Guardian contributor Sir Simon Jenkins, a prominent British columnist, engaged in one such dispute surrounding the films released in 2018. He deemed Vice, among others, “fake instant history,” criticizing the gross liberties taken with true stories like Cheney’s; Jenkins expressed concern about adaptability, inquiring as to “what a history student is supposed to make of the film.” The response – the script writer encouraged those viewers to “conduct actual historical research.” His argument was fairly simple: films are not documentaries, and students should not look to Hollywood for a history lesson.