How would you describe your personality?

Whether it’s a BuzzFeed quiz proclaiming to tell you which Disney princess you’re most like or a well-researched personality test promising to reveal “who you truly are,” personality assessments have exploded in popularity recently. There’s something alluring about a test that promises to tell you something about yourself that you don’t already know; the results can make you feel seen, offering a bit of insight into who you are.

Personality typology isn’t new. All throughout history, people have tried to organize others into distinct groups based on their personalities. The ancient Greeks were presumed to be the first, dividing people into categories based on their temperaments. They believed that temperaments arose from the ratio of fluids in the body, also known as humors (black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm). While Hippocrates first developed the idea of humans having a careful ratio of humors that, if disrupted, could cause illness, Galen expanded on the idea and postulated that an imbalance could explain differences in behavior. Someone with more yellow bile than any other fluid, for example, would have a choleric temperament. This would explain their personality and why they make certain choices — someone with a choleric temperament would be more competitive as compared to someone with a phlegmatic temperament. Though the idea of humans having four temperaments has generally been debunked, the idea that different personalities generally correspond to traits of a certain temperament persists.

Many other personality theories have been developed since then, which led to the creation of personality tests. Interestingly enough, the first personality test was unveiled during World War I. The Woodworth Personality Data Sheet was developed out of an urgent need to screen soldiers for what was referred to as “shell shock.”

Now recognized as a symptom of PTSD, shell shock made it dangerous for people to serve in the army or fight in a battle. The symptoms would usually arise after soldiers were exposed to artillery shell explosions, and researchers thought that certain people would be more susceptible to developing it. So, psychologist Robert Woodworth set out to create an assessment that could be used to screen people for shell shock. The assessment asked simple yes or no questions, and considered the final tally of responses in each category rather than focusing on each individual answer — an aspect of the test that has lived on in other personality tests since then. In this way, the first personality test has had a far-reaching impact.

Now, personality tests are as ubiquitous as coffee shops. There are a number of resources available online that offer free personality tests, claiming to reveal “who you are and why you do things the way you do.” Many people take these tests for personal reasons; psychologists say that people are innately interested in analyzing their personalities and enjoy receiving validation about their best qualities. In some cases, personality tests can be required in the workplace. Proponents of workplace personality testing claim that it will help employees work more effectively with each other.

Among the most popular of these tests are the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the Enneagram Personality Test, and the Big Five Personality Test. These tests ask questions that measure certain aspects of your personality and sort you into a distinct personality type.

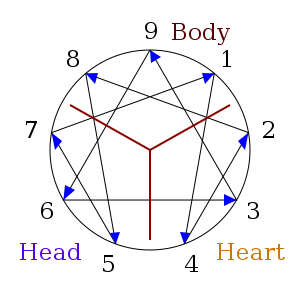

The Enneagram is a personality model that proposes the idea of nine personality types, each named after a number from one to nine. They each have certain characteristics that define them: Type Eight, for example, is described as “self-confident, decisive, willful, and confrontational.” The Enneagram was introduced to the United States by Claudio Naranjo, who learned about the theory from the Arica School, a school founded by Oscar Ichazo. Ichazo, a Bolivian philosopher, has been credited with formally creating the theory of the Enneagram. Prior to his findings, though, the basic theory of the Enneagram had already existed, tracing some of its earliest origins back to Western philosophy.

The purpose of the Enneagram is to discover the underlying motivations behind one’s actions. Though many professionals have classified it as a pseudoscience, proponents of the Enneagram maintain that it is a useful tool for gaining a better understanding of your personality.

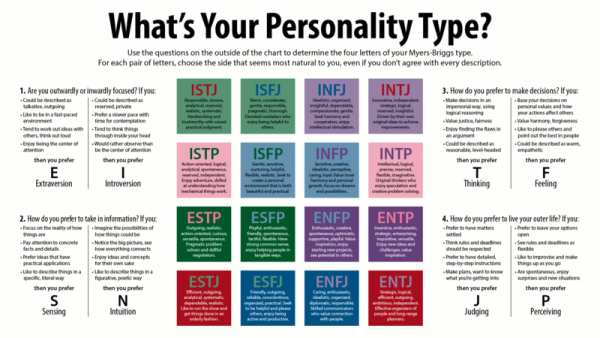

The Big Five Personality Test measures how high people score on certain personality traits (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and agreeableness). This is supposed to reveal how someone views and interacts with their environment. While generally considered to be more reliable and scientific than other personality types, the Big Five isn’t quite as popular as others, especially not the MBTI. And it’s clear to see why: upon taking the MBTI, you get assigned to one of sixteen distinct personality types, each with their own specific traits, possible career paths, and colorful avatar. There are also a plethora of resources on the MBTI online — there’s even a guide to which dessert you should make based on your personality type.

The MBTI was developed in the mid-twentieth century by two women with no formal training in psychology, a fact that has haunted their legacy to this day. Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers, worked together to develop the personality test during World War Two. American men were fighting overseas, and women needed to step up and fill in the jobs they left behind. Myers and Briggs thought that a personality assessment would be able to accurately sort people to the jobs best suited for them, so they got to work creating one using ideas from Carl Jung’s “Psychological Types.” Briggs was already quite familiar with Jung’s ideas concerning personality, but this was when she and her daughter first implemented the ideas and created a personality test based on them.

The result was the MBTI, which has grown more popular than Myers and Briggs likely thought possible — an estimated two million people take the test annually. The MBTI proposes a theory of 16 distinct personality types in four categories. Everyone is either an introvert or an extrovert, observant or intuitive, feeling or thinking, and judging or prospecting. The results of the test are acronyms consisting of four letters based on these categories, such as INFJ [introverted (I), intuitive (N), feeling (F), and judging (J)].

In a survey I sent out to a sampling of students at Bronx Science, I asked them to share whether they had taken a personality test before and the results they received from them. Ten out of 19 students said that they have taken the MBTI before, but most of them expressed doubt as to whether personality tests can truly reveal one’s personality.

Coye Chen ’26 said that she doesn’t believe that her MBTI test result was accurate because of the inconsistent results that she has received. “The answer changes every time,” she said. This is something that many people have brought up when criticizing the MBTI.

Fatima Ali ’27 noticed that in the three times that she has taken the test, she has gotten three different results. However, she also said that she identifies with her most recent result, which was ISTJ. “It was pretty accurate because I’m quite shy with people I don’t know, and I’m pretty dedicated to something when I start working on it,” she said.

This skepticism is not unique; many people have doubts about the reliability of personality tests such as the MBTI. An issue that some people have brought up is the apparent lack of test-retest reliability with the MBTI. Test-retest reliability, which refers to the consistency of a test’s results, is important to ensure the validity of assessments. This becomes especially important in the context of a personality test like the MBTI. If it can reveal your true personality type, your result shouldn’t change when taking the test a second time. And while people can certainly change throughout their lives, the MBTI maintains that your basic personality type cannot change.

(Image Credit: Jake Beech, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Myers and Briggs Foundation, a company that provides certification to administer the MBTI, claims that inconsistent test results are the fault of the person taking the test. They state that inconsistent results may arise from differences in one’s mindset when taking the personality test. For instance, someone who is feeling tired or anxious when taking the test a second time may get a different result that does not actually reflect their personality. But this brings up another issue: how do you know that you’re accurately answering the questions?

It may sound strange at first; after all, we know ourselves better than anyone, right? But what if we actually don’t?

What if someone is convinced that they’re an extrovert because they were brought up to believe that craving alone time after strenuous amounts of social interaction is selfish? What if someone is adamant that they are excellent in social situations but in reality completely unaware of their lack of social skills?

Humans are subjective, so there is naturally a limit to the extent that we can accurately analyze ourselves. But because personality tests rely on the objectivity of the test-taker, being unable to answer the questions truthfully could lead to a misleading result.

This doesn’t pose much of a problem when taking a personality test for fun; after all, you can just forget about the result if you don’t agree with it. But what about people who are taking a personality test for a specific reason, such as achieving self-awareness? And what about those who are mandated to take a personality test as part of a job application — a process that is becoming more popular — what if the result on their personality test prevents them from getting a job?

“I think these kinds of personality tests are a fun way to explore who you are and how you can describe yourself, but [personality tests] shouldn’t be a defining factor of who you actually are,” said Georgia Agoritsas ’26. If you truly enjoy taking personality tests, by all means, continue to do so. But if you find yourself becoming so preoccupied with personality tests that you begin to consider your MBTI type a key part of your identity, consider rethinking your relationship with personality tests; your results are not you, and you’re not them. And if you build up your identity on the basis of being an INFJ, you may be disappointed when the MBTI tells you you’re an ENFP next. After all, a few letters or a number cannot tell you who you are — only you can do that.

If you truly enjoy taking personality tests, by all means, continue to do so. But if you find yourself becoming so preoccupied with personality tests that you begin to consider your MBTI type a key part of your identity, consider rethinking your relationship with personality tests; your results are not you, and you’re not them. And if you build up your identity on the basis of being an INFJ, you may be disappointed when the MBTI tells you you’re an ENFP next. After all, a few letters or a number cannot tell you who you are — only you can do that.