“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

Many can resonate with this line. In 1848, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, upon realizing this, founded communism and changed the world.

Marx and Engels were German philosophers, journalists, and historians who, like many others, wanted to change the problems of poverty, exploitation, and corruption that plagued the nineteenth century. They believed that the root of these problems was capitalism, and so they proposed a new political theory. The Communist Manifesto was a political pamphlet introducing communism, a political theory that sought to end class struggles.

The definition of communism, as given by the Merriam-Webster dictionary, is “a system in which goods are owned in common and are available to all as needed.” However, as will be seen, communism was more than just that.

The Communist Manifesto established ten tenets of communism: the abolition of property and inheritance, progressive income taxes, confiscation of property of emigrants and rebels, central banking, state-controlled communication, transportation and education, government ownership of agriculture and factories, equal liability on all to work, and the redistribution of population.

By 1950, nearly half the world’s population lived under communist regimes.

Romania is hardly ever mentioned, and few know that Romania endured the most repressive communist regime in Eastern Europe and was ultimately the last to get rid of it.

Nicolae Ceaușescu, Romania’s famously oppressive communist leader, was born on January 26th, 1918, to a large family in the rural town of Scornicești, just outside Bucharest. He grew up poor and only received an elementary education. By the age of 11, he was working in a factory in Bucharest. By his teenage years, he was a rising leader in the Union of Communist Youth. After joining the underground Communist party, he was sentenced to thirty months in prison, specifically at the Doftana Prison in Brașov. Doftana Prison was known for the harsh treatment of prisoners. Here, Ceaușescu suffered physical abuse that left him with a permanent stutter.

While in prison, Ceaușescu met Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, a passionate communist. Throughout his thirty-month sentence, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej grew fond of Ceaușescu, instructing him on Marxist-Lenin teachings and introducing him to other communist party leaders.

After the Soviet invasion of Romania in 1944, Romania fell under communist control, giving Ceaușescu the perfect opportunity to rise through the ranks. By 1945, he was titled brigadier general of the Romanian army. Around 1952, Gheorghiu-Dej claimed power over newly communist Romania, and Ceaușescu, as his close friend, was able to increase his influence in government. Gheorghiu-Dej died of cancer in 1965.

Ceaușescu officially became president of Romania in 1965. He named his wife, Elena, deputy prime minister. By the end of his rule, he would be known as the oppressive communist leader who changed Romania forever.

Economics

My uncle, who lived under communism until the age of 14, remembers the struggles. Below are a series of quotes, all attributed to him.

“I remember the lines at the gas stations because of gas shortages. They could last for days.”

Ceaușescu’s goal through his policies was to eventually pay off all of Romania’s foreign debts. After Albania, Romania was considered the poorest country in Europe, and Ceaușescu was determined to change that title. In this respect, he succeeded. By 1989, every single dollar of foreign debt was paid off. However, this was not done without a price, the price of human life.

Romanian exports to the United States, most of which was petroleum, rose 163% between 1982 and 1984. At the same time, imports only increased by 10%.

The effect? Many Romanians could not enjoy the comfort of using petroleum. Winters were cold and harsh. Indoor electric heaters were banned. If someone in a building got caught using an electric heater, power would get cut off from the entire building.

“There were not many cars, but those who had them did not enjoy full comfort from having them. To save on gas, there were rules that limited the use of cars. For example, on even days, only the cars with even plate numbers could circulate, and on odd days, only those with odd plates. You couldn’t drive every Sunday – even numbers were allowed to drive on one Sunday and the next Sunday only odd numbers could drive.”

Drivers of state-owned taxi services, for example, would be entitled to 15 liters (less than 4 gallons) of gasoline a day, which would be enough for around 94 miles (150 kilometers). This would only cover half a day’s worth of driving.

Because of this regulation and restriction, many engaged in a second economy in which goods were bought and sold in U.S. dollars instead of Lei (the Romanian currency) and trade happened through bartering. Second economies are common in all communist countries, as it allows for production and exchange of goods for private monetary gain. In other words, it is a black market.

“The cars were not very expensive, but the prices were regulated by the government, not by supply/demand.”

To put the price into perspective, cars were around 70,000 lei (the currency in Romania), but the average monthly salary was only 1,800 lei. 1,800 lei is equivalent to 389 dollars today.

“This was the case for everything, not just cars. But specifically for cars, not enough of them were produced to cover the demand, so people would be on waiting lists for years until they could get one.”

“And by the way, the cars were pieces of garbage.”

Every summer, I visit my grandparents in Drobeta-Turnu Severin, a city in the west of Romania, right across the Danube River from Serbia. Characterized by sprawling boulevards and the promenades along the river, my summers there are spent playing hide and seek and soccer in the backyard of my grandparents’ building with the other children on the block. My grandfather’s car is a white Dacia. The seats are loose and low. He never drives the car over 40 miles an hour. Once, he lifted the hood of the car and it looked too antiquated to see in real life, like something that belongs in a vintage store or a scene straight out of an old movie.

He bought his car during communism and has kept it ever since.

Shortages and Rations

Fuel wasn’t the only commodity that was rationed. So were basic necessities, like food.

Communist countries, even today, generally suffer from food shortages and production mismanagement. The reason for this is central planning, a business ownership repression tactic that was adopted by communists to exert government control over aspects of the private sector. Instead of the usual supply and demand in capitalist countries, the government would set the prices and amount of production through ration books.

“I remember going to the grocery store and finding sometimes only frozen mackerel in the meat and fish section. There were times with shortages of bread when it would be rationed, meaning that you couldn’t buy more than one loaf of bread per person.”

The official rations per person were as follows: 300 grams of bread per day, 500 grams of cheese per month, 10 eggs per month, 500 grams of pork or beef per month, 1 kilogram of chicken per month, 100 grams of butter per month, 1 kilogram of sugar and flour per month, and 1 liter of oil per month. Even these amounts were often further rationed or unavailable.

“I remember my father was very happy when he managed to buy milk. The supply was limited, so people woke up early in the morning to queue in front of the store. It was on a first come first serve basis, and not everybody would return home with milk.”

“Sometimes we were waiting in lines in front of the stores for hours in anticipation when the news spread that they were bringing chicken or pork meat. The quantity was limited per person, so my mom would bring me and my brother to wait in line so she could buy three chickens. After waiting for over an hour to buy chicken, I was happy that I could go play with my friends. Suddenly, one of our neighbors, who was still waiting in line for her turn, asked my mom to ‘borrow’ me and my brother, so that she could also buy three chickens. My mom agreed, because of course we had to help our neighbor, and I remember being disappointed that all my plans for a soccer game were ruined. While waiting in line, I was drilled on how to lie, if asked whether I was counted before. Luckily, by the time it was our turn again to enter the store, the person at the counter did not recognize us from before.”

Not only were there shortages of food, but certain ‘exotic’ foods were rarely ever seen. I remember that, when I was younger, eating an orange in my grandmother’s house was often followed by a remark on how, under communism, you could never find an orange! My uncle’s experience was with bananas.

“In all my fourteen years of life in communism, I only saw a banana once! Mind you, I didn’t get to taste it. Meanwhile, Romania was one of the biggest exporters of bananas in Europe. How was this possible? Romania had economic relations with countries in Africa that would pay for things they imported with exotic produce, such as bananas. Only small quantities of exotic Western stuff would make it to Romania, and those would only be available to the privileged few of the political elite.”

In a way, it’s ironic. Romania’s exports suggested that it was a wealthy and successful country. But somewhere along the way, the people were forgotten.

In Ceaușescu’s palaces, however, all remained well. Despite a crumbling economy, he did not hesitate to engage in expensive building projects commemorating his reign. This included the Danube-Black Sea Canal, an unnecessary $1.2 billion civic center, and a $1.8 billion irrigation project.

To compound the problems, heat and electricity were also rationed. Again, this was done partly because Ceaușescu wanted to pay off all debt and make Romania entirely self-sufficient.

“I remember the times when I used to do my homework at the light of a candle because electricity was cut regularly for a few hours on certain days.”

Most households were allowed to have one 40-watt light bulb. To put that into perspective, a typical ceiling light today is around 60 watts.

For many Romanians, the winters were cold and harsh. Indoor electric heaters were banned. If someone in a building was caught using an electric heater, power would be cut off from the entire building. Street lights were often turned off to save on electricity, leaving entire streets dark. Romania became a country of darkness, lacking even the light to notice the suffering around them.

Land Ownership

Another tenement established in communism was the abolishment of private property. For my uncle’s grandfather, Contraș Traian, this was devastating.

A key belief of communist philosophy is the concept of state ownership in a society, the belief that people should not be allowed to own private land and that instead property should be under “collective ownership,” which often meant that the government had total control over the land.

“Contraș Traian was a veteran from World War II. He went through incredible hardship to buy a piece of land and build a farm for his family. When the communists came to power, however, his land was confiscated.”

This is one of the problems with communism. It tries to make everyone equal, to take away what they have accomplished in life, and level it out for the common good. But the reality is, everything that people had, including land, was simply snatched from their hands, leaving them wondering what they were working for in life.

“He was lucky that his property was not yet fully booked in his official records. Those who owned more than 10 hectares (24 acres) were considered ‘enemies of the people.’”

Now, when my family and I fly to Romania over the summer, we visit Contraș Traian’s piece of land. The road begins from the edge of the town Tașnad and stretches out into fields patterned like a quilt with crops forming a variety of shades and sizes. We bike there, kicking up clouds of dust, swerving around lizards, and bouncing on the seats while biking through uneven grass fields. It is peacefully magical – you feel as though you could remain there forever, biking and picking wild pears and watching the grasshoppers somersault upon sensing your steps. Tucked away in these fields is our forest, a patch of land resembling a tuft of hair that remained unshaven. When you enter the forest, light streams in through the trees and glows like a haze around you. You walk through the curtains of branches and leaves as though you are parting the curtains of heaven.

This is a fraction of the forest we once owned. Now, we preserve it with all our might. But it broke Contras Traians’ heart when the state seized that which he had worked so hard and for which he dreamed so dearly.

“My grandfather was so upset that his land was confiscated that he said he regretted not having the weapon he carried during the war any more, so that he could defend his property. He said this to a friend in a private conversation, but someone heard him and informed the police. They arrested him immediately, took him to the police station, and beat him so hard that he could not sleep on his back or sit on a chair for a week because of the pain. He suffered for months.”

“The only reason he escaped without imprisonment was because a neighbor who worked as a secretary for the police chief was friends with him and she told the police, to help free him, that he was just a ‘dumb farmer’ who did not mean what he said and that he wasn’t worth wasting their time.”

“There was no trial and, in a way, he was lucky, because such a statement against the regime was a crime punishable with many years in prison.”

Others who were resistant suffered much darker fates. But there was a problem with refusing to comply – the government could easily one-up you.

Those that resisted “would be rounded up from their homes, in the middle of the night, loaded in freight trains and dropped in forced labor camps in the middle of nowhere with no decent shelter, running water, or medical assistance. Many would just die.”

It was the General Directorate of People’s Security, called the Securitate, that would be in charge of doing this. The Securitate was the Romanian communist secret political police, responsible for enforcing rules. The Securitate was modeled after the Soviet police. It usually targeted “opponents” by discrediting them or encouraging them to emigrate, but sometimes through illegal house arrests and deportations.

“My grandfather was telling me that his Jewish neighbors, a peaceful, religious family of twelve, including babies and toddlers, disappeared one night.”

They never returned. Such was the fate of anyone who even questioned the regime.

The justification was that they were ‘enemies of the people.’ Communism was defending “liberty and equal rights” and anybody who opposed even the slightest rule would be considered power-hungry criminals who could be dangerous. But how much of a threat was this Jewish family?

Education

Another change under communism was the educational system. Religious and private schooling did not exist. Attendance was compulsory until the end of twelfth grade.

All schools were free of charge, which benefited children whose parents could not afford to send them to prestigious schools. However, these free schools were utilized as major platforms for communist leaders to indoctrinate children with the communist ideology.

“There was no private school allowed: they were all under government supervision. But that also meant that the content of the education was controlled and heavily politicized. History, for example, was re-written to emphasize the merits of the communist leaders, and how bad life was before they came to power. Also, because there was not enough space in schools, we studied in shifts, there was a morning and an afternoon shift.”

The curriculum was heavily censored, painting communists in a good light while displaying democracy as stifling. Children were trained to become future communist leaders.

Education was highly regimented in all facets, not just the curriculum but also teacher autonomy and classroom environment.

“I remember one instance in middle school when two rowdy boys had a fight during recess, and one of them threw an apple core towards the other one. He missed, and the apple core ended up hitting the portrait of the ‘supreme leader’ [Ceaușescu] and left a little spot. One of the teachers noticed the spot and an investigation was on the way.”

This type of incident was a scandal. The parents were immediately called down to the school and blamed for the children’s actions. All sorts of questions were raised.

Was this an act of deliberate defiance? Did these children learn this sort of anti-communist attitude at home? What kind of influence were the parents pushing? Are the parents ungrateful towards everything the supreme leader has done? These sorts of acts of defiance against the regime were the most severe because they posed a possibility of revolt against communism. The most important thing for Ceaușescu was to remain in power, and instances like these escalated very fast.

“Luckily, our principal had some common sense to appease the situation, and only the silly kids were punished.” But the parents could have been imprisoned.

Ultimately, Ceaușescu weaponized education, modeling his reforms after what he saw in China and North Korea, to nurture ideal people for an ideal communist society.

Propaganda and the Personality Cult

Perhaps the most ironic part about communism was that its original intention, to help the working class, was the opposite of what actually happened.

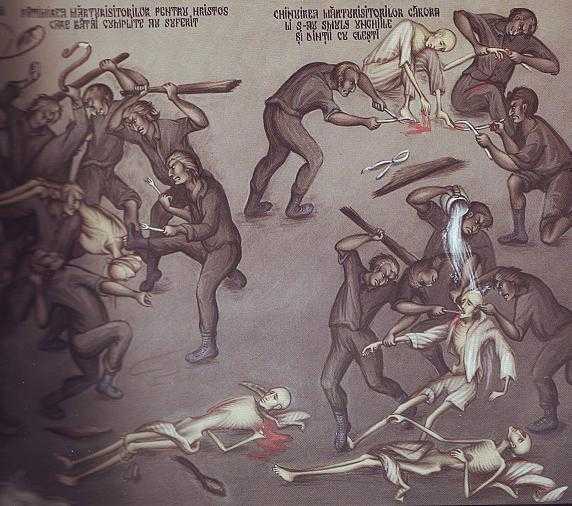

Romania specifically has come under criticism from major countries around the world during its time as a communist nation, specifically for the inhumane treatment of people.

So why was communism able to stand for so long? Propaganda was a widespread technique used to depict life under communism as being “idyllic.” The agenda behind the propaganda was to display life under capitalism as even worse, and that Ceaușescu deserves recognition and gratitude for allowing Romanians to live so well.

In a report on the role of propaganda in communism, the CIA said that propaganda aims to instill sentiments of nationalism and patriotism so that an attack against the regime is seen as an attack on the people. In other words, propaganda aimed to force people to conform to the government by pinning them against each other. All the components of propaganda are meticulously implemented to ensure the least amount of opposition and free thought.

This, for Ceaușescu, was the missing link. In 1971, Ceaușescu visited China, North Korea, North Vietnam, and Mongolia, all of which were communist at the time. Here, he noticed China’s Maoist propaganda and Kim Il-Sung’s (North Korea’s “Supreme Leader”) cult of personality. Upon arriving, he was met with parades with hundreds of thousands of people demonstrating their allegiance to the regime. They were forced to wave flags and dance and cheer.

A stenogram from a 1971 meeting with Romania’s Communist Party describes the experience. “We were met by hundreds and hundreds of thousands of people, however not in thick crowds – as is the custom in our country – but in an organized manner: with schools, brass bands, sports games, and dances. … I think we have to learn something from this since everything was in good order. … They said: we do not want any bourgeois concepts to get in here. … What I have seen in China and Korea is living proof that the conclusion we have reached is just. Consequently, from this point of view as well, it is a very serious preoccupation with educating the people in a revolutionary, communist spirit.”

Ceaușescu felt inspired. He wanted the same for Romania.

He expressed this new dream he had for Romania in the July Theses, with seventeen proposals that would trigger a cultural revolution. It included young people participating in large-scale construction projects (“patriotic work”), strengthening political ideological education in schools, and expanding political propaganda to be shown on radios, televisions, cinemas, opera, ballet, and art.

In Romania, magazines, newspapers, and radios would highlight the cultural achievements and material benefits that have followed since communists came to power.

But then people would go to supermarkets, and see empty shelves. People would notice their neighbors disappearing. People would hear hushed stories of scholars being tortured in prisons. People would see all this and they would wonder where all the great things the Romanian media and government boasted of were.

My uncle recounts this dilemma. “If you opened any newspaper or turned on the T.V., you would think you lived in some paradise! They would show the supreme leader visiting supermarkets where the sausages overflowed from the shelves in a mouthwatering abundance. New record highs in the production of any crop were proudly announced every day and gratitude was due to our supreme leader and infinitely wise wife, who had a supposed Ph.D. in chemistry but really only graduated elementary school and could hardly read.”

Television was, of course, severely limited. There was only one channel that could be watched for two hours on weeknights. This channel was dedicated to furthering the communist agenda. Ceaușescu’s activities and accomplishments were put on display, in all mediums, including the front pages of Romanian newspapers.

In a 1986 New York Times article, journalist David Binder wrote, “The Rumanian president has become a kind of a Communist king, due in large part to the systematic development over the last dozen years of a cult of personality that has equaled, or even surpassed, those of Russia’s Stalin, China’s Mao and Yugoslavia’s Tito.”

Bookstores were required to devote a showcase filled with twenty-eight volumes of Ceaușescu’s speeches. News kiosks had to do the same. Music stores were required to display records of his speeches. Painters and poets were required to produce works celebrating him. In Bucharest, triumphal arches wrote “The Golden Epoch – the Epoch of Nicolae Ceaușescu.”

At party rallies, even the highest-ranking communist officials were required to engage in ritual chants such as “Ceaușescu-Rumania, our pride and esteem!” In Târgoviște, a city in the south of Romania, a history museum had an exhibit of Romanian heroes. Ceaușescu and his enormous portrait monopolized the exhibit, looking down upon all the other busts of Romanian rulers and military leaders. Ceaușescu and his wife’s birthdays were seen as national holidays.

It all feels very dystopian.

The cult of personality and propaganda came hand in hand with surveillance and suppression of free speech. Communist theory never addresses this problem – it seems to support free speech when it is beneficial to the entire society. However, as soon as communism becomes the ruling system, oppositional speech isn’t seen as beneficial and is thus severely restricted.

Ceaușescu wanted to be perceived as a god, a supreme being, the savior of the Romanian people. His titles included “Leader” and “Genius of the Carpathians.” And while some Romanians believed him, most held a deep hatred for him. When communism fell, it collapsed violently, with revolutions and bloodshed.

In the 1980s, Ceaușescu was horrified by the changes taking place in other communist countries, such as the Soviet Union. The glasnost, a policy that expands individual freedoms, and perestroika, a movement for economic renewal, were taking place in the Soviet Union, and Ceaușescu made it clear that Romania would not be doing the same.

In December of 1989, protests broke out in the city of Timișoara, in western Romania. These protests were triggered because of one minister who was threatened for criticizing the regime. But this event embodied the beginning of the end for communist Romania. On December 17th, security forces opened fire on protesters, wounding hundreds of people.

In response, Ceaușescu called for a rally in Bucharest on the 21st, which he described as a “spontaneous movement of support.” He began his usual discourse when the audience suddenly began to jeer. At first, Ceaușescu tried to silence the crowd, but protests eventually erupted, and he stoically fled to the Communist Party Central Committee headquarters.

That night, the police continued trying to settle inflamed protesters. By the next day, demonstrations were taking place all around the country as people gathered courage. Ceaușescu tried addressing the protesters again, but this time was met by a barrage of rocks and other objects. He and his wife fled from the roof of the headquarters building by helicopter. They did not make it far and were captured on the run later that day.

The secret police (Securitate) controlled by Ceaușescu wanted to regain control in this time of instability, but the army turned on Ceaușescu and battled the police. In the chaos that ensued, nearly 1,000 people died.

On Christmas Day of 1989, Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu were put on trial. Over the course of 55 minutes, they were found guilty of committing genocide, armed attack on the people, subverting state power, destroying public property, undermining the national economy, and attempting to flee Romania using public funds.

Throughout the trial, Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu refused to speak and refused to acknowledge these charges. The prosecutor asked the following questions: “Why did you ruin the country so much?”; “Why did you export everything?”; “Why did you make the peasants starve?”; and “Why did you starve the people?” And though the prosecutor noted that “we [Romanians] finally saw your villa on television, the golden plates from which you ate, the foodstuffs that you had imported, the luxurious celebrations, pictures from your luxurious celebrations,” Nicolae Ceaușescu repeated that he and his wife were normal citizens who humbly lived in apartments and devoted their lives to the wellbeing of the people.

No matter how many times Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu repeated that they did not recognize the court and they would not answer, the pain they inflicted upon the people and the disintegration of the Romanian nation stands testament to the genocide that was the Romanian communist regime.

Elena and Nicolae Ceaușescu received the death sentence. They were shot on Christmas of 1989. All their property was impounded. Today, their graves at the Ghencea Cemetery in Bucharest are simple, underwhelming in comparison to the lavish life they lived during the 24 years of their disastrously oppressive reign.

Communism Today

Today, the effects of communism in Romania persist. Ideals of the communist party continue to hurt groups such as the Roma people and disabled people. Their treatment in schools and perception in society is thought to be due to the beliefs that communists encouraged.

Five communist countries remain today: China, Cuba, Laos, North Korea, and Vietnam. Only two of these countries, Vietnam and China, can be considered “successful,” meaning they are economically stable. Even so, China is considered very capitalist. Its economy is cited as a “socialist market economy” because it conducts foreign investments, markets and farmers have partial ownership rights, and businesses compete and invest internationally.

Cuba, Laos, and North Korea struggle with a variety of issues including an informal underground economy operated by citizens, shortages of resources and basic necessities, and a low GDP per capita. Moreover, human rights are compromised. North Korea is known for its blatant human rights violations, including restrictions on the freedom of movement, the right to information, the right to health, and the right to free speech. These countries continue to show the ineffectiveness of communism.

The argument that gets repeated today is that communism was the right idea but was carried out wrong. People say that the leaders of these communist countries became abusive, which was not the goal of communism, and that communism could work in an ideal world.

I posed the same question to my uncle.

“Do I think it will ever work? Not under the premises which constitute the base of a free society: freedom of speech, meritocracy, private property, and freedom of faith. All the liberties we have in place contradict what communism turned out to be. Maybe, in a future where people are designed to be perfectly equal in all their qualities, from intelligence to physical features and abilities, and identical in all their wants, inputs, outputs, and beliefs…communism would work.”

There are many flaws to communism that prove that it can never work. The planned economy proposed by communists is just one example, as it ignores supply and demand and the “invisible hand” that guides the economy in capitalist countries.

Most importantly, communism relies on specific human patterns that simply aren’t attainable. Every person living under communism would have to be content working without the hope of future achievements, such as advancement in a profession or making more money. People would have to be content buying the least amount of materials necessary for life and willing to put aside their hard work and focus on a community effort.

Of course, communism remains an extremely nuanced concept. I cannot answer the question of whether it can work or not. I cannot even describe the full extent of the communist experience in Romania in one article. My uncle’s insight provides a view of what communism was really like, not in theory but in reality, and it is just another story among millions of others showing that communism is detrimental.

Everything has its flaws. Capitalism has its flaws too – we see these flaws, every day. But let us not lose sight of reality when it comes to radical political ideologies such as communism.

Whether communism could or could not be successful is debatable. And through these debates, the questions that desperately require an answer are: does human nature permit communism to work? Are we too greedy for communism to be successful?

Until those questions are answered, the only proof we have is the long history of failures and blood spilled throughout history. Romania is just one example of how communism destroyed a country and its people.

In a 1986 New York Times article, journalist David Binder wrote, “The Rumanian president has become a kind of a Communist king, due in large part to the systematic development over the last dozen years of a cult of personality that has equaled, or even surpassed, those of Russia’s Stalin, China’s Mao and Yugoslavia’s Tito.”