Whether it is ink smudging on paper or the clattering of keyboard keys, writing is a unique process marked by inspiration, procrastination, and attention. It may serve as fodder for a rant or mark the end of a doctorate, taking different shapes and in different mediums. Writing is how we represent language visually, using recognized markers. It is the technology that defines the world.

As Dr. Hye K. Pae, Professor of Psycholinguistics and Applied Linguistics at the University of Cincinnati and writer of Script Effects as the Hidden Drive of the Mind, Cognition, and Culture, emphasized, “Written signage serves as a pivotal aspect of a culture’s general anthropology, delving into both sociocultural and language-specific dimensions. It plays a crucial role in general anthropology by revealing fundamental aspects of human civilization, reflecting sociocultural contexts of the past, and responding to evolutionary pressures.”

Its importance spans as broadly as the development of nations and as specifically as the brains of individuals. As Pae reiterated, “The script one grows up with also plays a multifaceted role in influencing cognitive development. From shaping basic cognitive processes such as attention and memory to impacting more complex functions such as problem-solving, the script used for reading affects how users perceive, process, and interpret the world.”

History of Writing

Writing developed independently in the Middle East, China, and Mesoamerica. These developments would become the basis for all written word, utilizing language and culture to promote communication.

Initial writing systems are known as “proto-writing.” From as early as 7000 BCE, these likely contained no natural language (language that occurs without prompting, which develops with time) but relied predominantly on ideographic or mnemonic symbols. Signs include Vinča symbols — known as the “Danube script” — the Dispilio Tablet of the late 6th millennium, and the Indus script, used from 3500-1900 BCE for short inscriptions. Though known as a staple of the Neolithic era, this method served as a milestone for formal writing. This is present in the Inca’s quipu – “talking knots” — and Uyaquk pictographs used before the development of the formal Yugtun syllabary for the Central Alaskan Yup’ik.

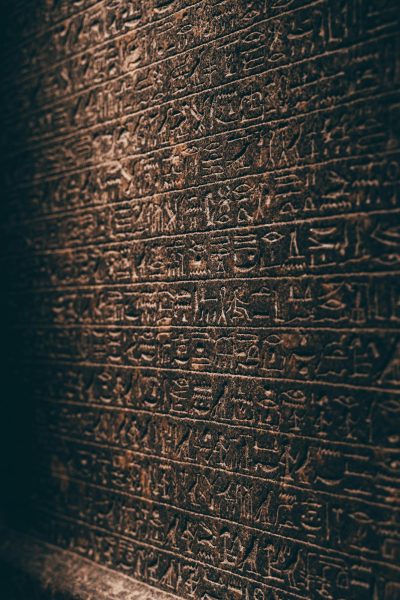

By 2700 BCE, Egypt had developed approximately 22 hieroglyphs to represent symbols. These included a consonant and, sometimes, an additional vowel. Egyptian glyphs helped structure pronunciation, demonstrate grammar patterns, and transcribe loans and names. However, these were not systems used for speech.

Around 1700 BCE, the Proto-Sinaitic script, resembling an alphabet, was developed, appearing to be inspired by Egyptian hieroglyphs. Some historians believe it was an early form of Hebrew, but this argument is laden with controversy. However, it is confirmed to be a Semitic language.

This evolved into the Proto-Canaanite alphabet, which then advanced into the Phoenician and South Arabian alphabets. All of these alphabets — referred to as abjads – lacked vowels and can still be found in scripts like Arabic.

The Phoenician alphabet, containing only about twenty-four distinct letters, redefined scripts by allowing the possibility of writing down different languages (as it transcribed words phonemically) and attracting a larger pool of users (due to its comparative simplicity). As the Phonecians colonized the Mediterranean, the script spread across the area, where it was largely adopted. Greece added vowels to the letters, creating the first alphabet as many today would view it, marked by vowels and consonants, which made explicit symbols through one script.

Greek colonists then brought a form of the alphabet to the Italian peninsula, where it further developed into different alphabets, with one being the Latin alphabet that inspired the Romance languages.

Characteristics of Writing

The two types of writing are phonologically-based systems, where the symbols represent sounds, and non-phonologically-based systems, where written symbols represent meaning.

Pictographic writing centers around pictorial representations of objects, where reading entails a recognition of symbols. This dates back to 3000 BCE in Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Ideographic writing has abstract meaning, rather than solely pictorial representation, found in systems from the Near East between 2500 BCE and 100 BCE. This includes cuneiform, using a wedge stylus to press imprints into clay tablets.

Logographic writing uses characters (linguistic units) that tend to be part of words instead of whole ones to communicate. Literacy, by this metric, may be thousands of characters.

Pae provided insight into the structuring and accessibility of alphabets, sharing “Korean alphabet, Hangul, adheres to the alphabetic principle while being configured in blocks. In the alphabetic principle, written signs represent sounds (phonemes), and syllables are formed by combining an array of letters. This contrasts with the Chinese writing system, where signs signify meaning (morphemes), and each character represents a syllable. The packaging of letters within syllabic blocks in the Korean alphabet eliminates the need for readers to parse syllabic units during reading, enhancing overall efficiency. Hence, it can be asserted that the Korean alphabet played a significant role in fueling South Korea’s rapid economic growth, serving as a compelling example of the script-cognition-culture link.”

Alphabet in Study

The study of letters and letter combinations within a language has its own unique term — orthography. Most languages that possess alphabets have rules surrounding spelling, enabling readers to sound out words that they do not know and guess the arrangements of new words by linking letters to sounds. Orthography thereby bridges the gap between spoken and written language, making comprehension easier. It is this process that allows young students to connect a word’s pronunciation and meaning to long-term memory.

Furthermore, reading and comprehending languages may depend on location. Not all languages have the same subject-verb-object order or the same direction of letters. Some languages are read from right to left (such as Hebrew and Arabic) or written from top to bottom (such as Mandarin and Mongolian). Directionality, or the written orientation of language, can influence how people spatially display time, rooted in how the eye and hand movements are trained to work. Learning to read trains the eye to associate chronology visually.

In large part, direction ties to location. East Asian languages, frequently written top-to-bottom, used to be found on scrolls, where people would more easily be able to jot down words while one hand held the paper.

Middle Eastern languages are also typically right-to-left, as people used stone tablets. For a majority right-handed population that would hold tablets with a left hand and a chisel with the right, writing from right to left would be more logical. To reverse the direction of the script would increase the possibility of them accidentally hitting their hand with a hammer. The most prevalent right-to-left languages are Hebrew and Arabic, both of which have a background in the Aramaic alphabet. More languages, including Urdu and Persian, then adapted the latter to their own dialects.

The older the language, the greater the likelihood of right-to-left writing because it predates paper. Once paper was largely adopted, at approximately 100 BCE, writing from left to right became a matter of access; it prevented ink from smudging.

Early English utilized a runic alphabet from right to left. Only with the replacement of the Latin alphabet did the directionality shift. Most languages go from left to right, especially languages rooted in Latin and Southeast Asian writing. This fundamental shift dictates how people visualize space, time, and chronology, creating fascinating cultural comparisons.

The Power of Scripts

Scripts represent cultural needs and history. By following their usage, especially alongside similar regions, we can understand politics, assimilation, and the interaction of groups.

Pae said, “Scripts serve as visible markers reflecting linguistic traditions, sociocultural characteristics, and political dynamics, contributing to the manifestation and reinforcement of culture-specific differences. A compelling illustration is evident in the Middle East, a region known for its diversity of ethnic and cultural groups. Non-Arab states like Iran, Türkiye, Israel, and Cyprus, though geographically situated in the Middle East, are distinct from the Arab world. Notably, these non-Arab Middle Eastern states utilize their own spoken and written languages, setting them apart. For instance, Iran employs Persian, written in the Perso-Arabic script, derived from Arabic with modifications and four additional letters. Türkiye adopted the Turkish alphabet, a Latin-script system with alterations in 1928 post the Ottoman Empire’s fall. Israel uses Hebrew and its unique alphabet. Cyprus, with Greek and Turkish as official languages, commonly writes Cypriot Greek in the Latin script. Their divergence from the scripts of the Arab world becomes a powerful expression of their cultural identities.”

In a different vein, constructed languages — “conlangs” — are languages intentionally created for real-world or fictional speakers. In other words, they are people-produced languages made to be learned by others and used to build community, rather than a naturally evolving language.

Occasionally used as projects for student linguists or in coursework, this intentional invention is growing in popularity for understanding fandoms, imaginary geographies, and virtual communities.

The Next Steps of Alphabet

Writing is the foundation for understanding the world around us, particularly in this digital age.

As Pae shared, “The surge of virtual media, encompassing digital text, digitized images, and advanced technology systems like augmented reality, has reshaped the communication landscape, influencing both the structure and function of language and script. These multifaceted transformations are primarily directed toward embracing multimodality, informal abbreviations or acronyms, the introduction of neologisms, and the emergence of new communication genres, among other shifts.”

Fundamentally, the way we approach language is shifting with technology, and understanding its roots has become all the more important to preserve our history, understand the present, and teach our future.

Fundamentally, the way we approach language is shifting with technology, and understanding its roots has become all the more important to preserve our history, understand the present, and teach our future.