The United States is an anomaly among its peers; the majority of the country is highly unwalkable. According to Planetizen, walkability is a planning concept that encourages mixed-use, high-density neighborhoods where people can access essential services and amenities on foot. In many U.S. cities or towns, walkability doesn’t exist. A car is essential to American living.

That’s where Strong Towns comes in. Strong Towns is an advocacy group focused on creating “strong” American and Canadian urban areas. Their mission is to advocate for all cities, no matter their size, to become safe, livable, and inviting. Alongside that is a commitment to replacing the development pattern that they call the “Suburban Experiment.”

Contrary to what the name might suggest, the Suburban Experiment is not limited to suburbs; it extends to urban and rural communities, as well. The Suburban Experiment refers to a concept in which all structures are built at once, leaving no room for further development

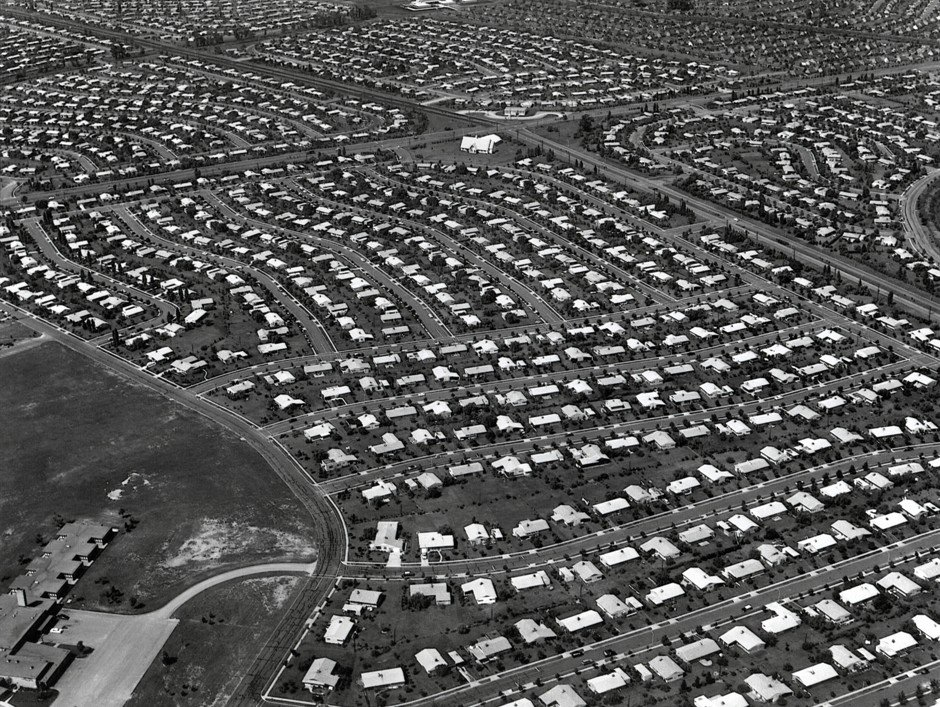

An example of this is Levittowns. William Levitt, considered the father of modern suburbia, worked to create these picture-perfect homes and neighborhoods. Taking inspiration from Henry Ford, Levitt and his team constructed the houses in an assembly line-like manner. The neighborhood was built to avoid any semblance of urban life. Instead of straight, grid lines, Levittowns utilized curves. Instead of public transportation, Levittowns prioritized automobiles. It was at this time when automobiles were seen as a sign of status. Subways, buses, trams, streetcars, and trolleys were viewed as remnants of the old America — the poorer America. The fully finished Levittowns appealed to white middle-class Americans.

Since Levittowns were built so quickly to accommodate the needs of white veterans, there were no provisions to allow any new developments. So many housing developments followed the example set by Levittowns, leading to huge swaths of the country being transformed into stagnant towns. Levittowns were the poster boy for the Suburban Experiment.

Strong Towns wants a return to the “Traditional Development Pattern”: an approach for growth which can be described as continuously improving and developing cities with a focus on people, not cars. TDPs can be seen across the world since most cities were planned to be improved, not finished.

An American example of TDP would be New York City. New York City was not built in a day, instead being a product of centuries of building. However, during its developmental stages, there was a focus on citizens’ convenience. That’s why there were streetcars running through the city – it was just a faster way of moving around. Those streetcar routes were eventually torn up and turned into bus routes, but those bus routes still serve the same purpose, to transport people around the city.

Alongside the streetcars came the subway system. The New York City subway system is incredibly old, first opening to the public on October 27th, 1904. The subway system was created because of the influx of new immigrants and to accommodate the massive population growth. New York City looked to other cities like London, which opened its subway in 1863. The first subway served only Manhattan, but soon, the subway lines grew into the outer boroughs.

Despite its long history, New York City is still developing today. On the public transportation front, there’s the Second Avenue Subway, meant to ease congestion on the Lexington Avenue lines (the 4, 5, and 6), a future project to extend the Q line to 125th Street, the IBX meant to connect Brooklyn and Queens, the implementation of new subway cars on the Staten Island Railway and the 8 Avenue lines (the A and C), along with a multitude of other improvements. On the car-dependence front, there are efforts to limit the number of cars going through Manhattan with congestion pricing, which is a policy that charges drivers for entering different zones, along with vehicle caps, a limit on the number of vehicles, on certain highways and expressways like the Cross-Bronx Expressway.

While many cities throughout the world follow this traditional development pattern, those in the U.S. do not. Some of the biggest U.S. cities have experienced a massive population spike, yet their city planning followed the suburban experiment, not the traditional development pattern. The suburban sprawl defines the U.S.: instead of dense neighborhoods, we have sparsely populated ones and neighborhoods that are farther away.

Reid Ewing, a city and metropolitan planning professor, points out four key components of urban sprawl: low-density housing, segregated land use, a lack of local town centers, and limited street connectivity. Low-density housing refers to areas where most of the housing comprises single-family homes or buildings with a small number of units as opposed to apartments. Segregated land use, also known as land-use restrictions, describes when a property is limited in its developmental potential because of the area it is in. A lack of local town centers means that there’s no place for the community to meet and discuss any incidents or events. Limited street connectivity describes streets that are not attached to each other, making it more difficult to get around, and decreasing the walkability.

Strong Towns aims to combat these four key components with more high-density housing, the elimination of restrictive zoning laws, more local town centers, and more street connectivity.

Strong Towns have been taken more seriously in recent years. In September 2023, the U.S. Senate held “Housing Supply and Innovation,” a hearing that saw many experts speak on the housing crisis. A board member of Strong Towns, Gregory Good, spoke at the hearing, and focused on how the U.S. could fix the housing crisis. Good said, “Public and private financing incentivizes large-scale projects with high concentration of high-end units over small to mid-size development at lower densities. Therefore, we don’t have homes where we need them at the price most Americans can afford.” Representative Jake Auchincloss of Massachusetts and Representative Mike Gallagher of Wisconsin are two Congressman who actively support Strong Towns. It might seem trivial to celebrate having just two representatives sympathetic to Strong Towns, but it signifies increased public acknowledgement and political endorsement of the Strong Towns movement.

While there is the national Strong Towns organization, there are smaller local conversations where members of Strong Towns can come together and create change. There are ‘Local Conversations’ branches for larger cities like New York City, San Antonio, Ottawa and smaller cities like Los Gatos, California, Kittanning, Pennsylvania, Zachary, Louisiana, and Durant, Oklahoma. These ‘Local Conversations’ take place either virtually or at in-person meetings, in order to discuss bike lanes, new housing and commercial developments, and the possibility of new transit. These ‘Local Conversations’ involve professional urban planners, civil engineers, and people who just want walkable cities.

There’s also the ‘Community Action Lab’ that puts Strong Towns ideals into motion. The program involves different communities assembling a plan for what they want to improve, and then Strong Towns comes in and helps them execute that plan. The ‘Community Action Lab’ lasts two years, and during those two years, communities end up facing the facts of their financial challenges head on, addressing the impacts of resource-draining growth, grappling with the causes of pronounced economic disparities, and changing their reliance on fragile revenue streams. All of this leads to communities becoming stronger. Not only do they work on creating strong economics, but they also work to create communities in which people are more politically-engaged.

While Strong Towns has garnered many accolades for their podcasts, articles, and courses, many of the ideas they propose have been controversial. One idea is the 15-minute city/neighborhood. The 15-minute city was first proposed by Paris urbanist Carlos Moreno, and urban planners have transferred the concept from paper to real life.

The 15-minute city has been criticized for being something out of George Orwell’s 1984, communist, and undemocratic. Some people believe that 15-minute cities will lead to the government forcibly taking away cars. Will that happen? Probably not. But Strong Towns needs to address it. Misinformation is everywhere, and education is key to stopping misinformation.

Strong Towns has gotten many people interested in urban planning. More people are questioning the way our cities are built, more people are interested in redesigning cities from the ground up, more people are interested in higher-density housing, and more people are interested in building better public transportation. A large portion of this enthusiasm can be attributed to Strong Towns. With Strong Towns’ influence increasing, there is hope for American cities’ walkability. Imagine a world where major U.S. cities have reliable transit, or a world where cars are not the priority. This can be achieved through advocacy groups like Strong Towns.

The United States is an anomaly among its peers; the majority of the country is highly unwalkable. According to Planetizen, walkability is a planning concept that encourages mixed-use, high-density neighborhoods where people can access essential services and amenities on foot. In many U.S. cities or towns, walkability doesn’t exist. A car is essential to American living.