The Lost Stories of Bengali Immigrants in the United States

Bengali immigrants have been living in the United States since the late 1800s, but they are rarely discussed in the context of American History.

In addition to the book, Vivek Bald also directed a documentary on Bengali Harlem in 2022.

My father left Bangladesh in 2006 with a promise to my mother that he would be back in a few months to see her and their new baby. He stayed with an old neighborhood acquaintance for the first few months in New York City. They took him to get his social security number and a job. Eventually, he moved to a co-living arrangement where he and 5 other people in similar situations shared a 3 bedroom apartment. When my mother and I came to the U.S. 6 years later, my dad moved out and the next person moved in.

His story reflects one of the many of the 21st-century South Asian immigrant stories in the United States. In the late 1800s, things looked a bit different.

Instead of landing at JFK airport on a Boeing 777, Bengali peddlers attempted to achieve their American dream through the immigration station at Ellis Island. While the majority of early immigrants were traders, making their profits by selling embroidered silk goods, eventually more Bengali people came to the U.S. with the prospect of settling and starting a new life. Early peddlers did not necessarily come to the United States to settle down and establish a new life in American cities.

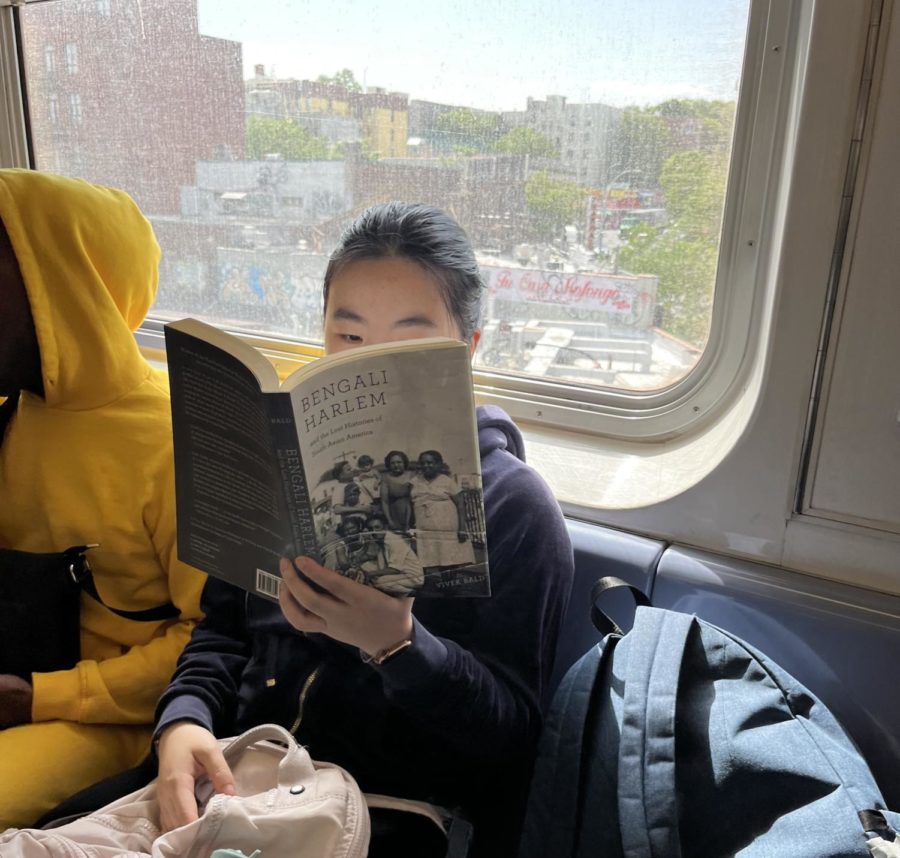

In his book Bengali Harlem: The Lost Histories of South Asian America, author Vivek Bald explores the intricacies of the lives of these Bengali peddlers throughout America. Bald is a professor of Comparative Media Studies and Writing at MIT, as well as a writer and filmmaker. Bald unearths the hidden stories of Bengali peddlers in the United States through the stories of various Bengali descendants.

Bald presents his research meticulously, creating a vivid picture of how Bengali immigrants lived in New Orleans in the 1890s. He explains the racial binary in the South and how that changed both the lives of South Asians and African Americans. Since the rigid lines of race in the Jim Crow era only allowed for the distinction between “colored” and “uncolored,” upon arrival in the United States, Bengalis who often had darker skin tones were placed into the same category as African Americans. Eventually, they were separated into their own category: Hindoo.

In New Orleans, Bengali businessmen, or Hindoo peddlers, eventually assimilated into life in the South. They stayed in African American communities and started families with African American women. As middle-class tourism increased in the South following the restoration of white supremacy through Jim Crow laws, the demand for “oriental goods” such as silk and rugs increased, improving the success of Bengali businessmen in the region.

Being “Hindoo” granted Bengali peddlers certain degrees of freedom. Unlike their Black counterparts, Bengali peddlers were not bound by the same circumstances and expectations of servitude and inferiority in American society. Bengalis could also travel with a greater degree of safety through the South and many segregated cities.

However, the distinction between the two demographics only protected the Bengali immigrants to a certain extent. Ultimately, Bengali peddlers and African Americans were tied in the same race for social mobility and equity in American society. As Bald puts it, “The hue of their skin ultimately determined where they return at the end of the day, the type and the quality of the houses in which they would live, the health conditions they would face, and the public facilities they could and could not access, and the risks that attended their daily movements.”

In the 1900s and 1910s, peddlers Solomon Mondul, Abdul Aziz, Tazlim Uddin, and Abdul Goffer Mondul, followed the lives of the hundreds of immigrants who resided in Storyville, New Orleans. After going all over the city to sell their goods all day long, these workers came back home to small, cramped spaces, housing about eight hundred square feet with several men living together in each house.

This created a sense of fictive kinship among the peddlers, who grew close from sharing such intimate aspects of their lives; they shared meals, beds, and even took care of each other during times of illness. Bald includes the recollection of an Indian student, and how, “They live in groups [and] you often notice them in their pajamas, sitting at ease, playing cards and gossiping, mostly about old fashioned things.”

However, with the implementation of more stringent immigration laws in the United States throughout the 1910s and 1920s, the once growing community of Bengali immigrants dwindled.

Motivation and Legislation

Bald gives the reader a holistic approach to Bengali history in America. He does not simply tell the reader Bengali stories in the United States or what happened after they arrived, he explains the motivations and events that led to their move.

Bald quoted a steamship laborer, Amir Haider Khan, who wrote, “Working in the coal bunkers through the Red Sea was such hell that the firemen had to pour buckets of seawater over their bodies before opening the furnace door to throw coal inside, or rake the fire.” Khan’s story exemplifies the harsh working conditions on British steamships. On these ships, Indian workers were exploited and forced to work in tough conditions without much reprieve. If anyone even as much as left their posts, they faced the possibility of being killed by British officers.

These harsh working conditions did not deter Indians from maritime work. The prospect of earning money and creating a business in America led to the eventual rise in Indian ship jumpers in the Northeastern ports of America.

As more and more Bengali seamen jumped from British ships and stepped foot onto the US, their presence became more pronounced. American reporters criticized the customs and habits of the Bengali peddlers describing their praying rituals as a “weird [funeral] ceremony,” as well as not eating pork. These comments reflect the many different ways Bengali immigrants were alienated upon arrival in the United States.

Although many share similar stories of working in the engine rooms of British ships, seamen who jumped ships were from various parts of the Indian subcontinent: Calcutta, Bombay, Madras, Sylhet, and Punjab. These migrants were not the monolith that they were often presented to be. Many folks continued to maintain their cultural customs while adopting American cultures.

There was a rise in anti-Asian immigration legislation in response to the growing population of South Asian immigrants in the United States. Opponents of Asian immigrants such as Andrew Furuseth sponsored various regulations deliberately designed to prevent East and South Asians from not only coming to the United States but also from working on merchant ships altogether. Language requirements for the Seamen Act included language requirements in order to work on the ships that entered US ports. Eventually, such acts led to panic amongst Americans regarding Asian immigrants. Many Americans believed that as Bengali immigrants trickled into the United States, they would threaten the already established social hierarchy in America. The panic and anti-Asian sentiment eventually culminated in the 1917 Immigration Act which tightened America’s borders and barred Asians from accessing American ports.

Legacies of Bengali Immigrants

Bald includes the story of Habib Ullah, who was a co-owner of the Bengal Garden, a Bengali restaurant on the Upper East Side. Habib and his wife, Victoria Echervaria Ullah, met in East Harlem, right after Victoria moved to the United States from San Juan, Puerto Rico. Habib is from the district of Noakhali, Bangladesh, and moved to India at fourteen. He found a job as a steamer and eventually found a jump ship at the Boston port. In the 1930s, he made his way to East Harlem and settled in the region with other Bengali ex-seamen. Ullah worked with other Bengali people in the area, such as Ibrahim Choudry, and established his own business despite having limited knowledge of English. Choudry managed the finances, while Ullah took care of the cooking.

Ullah and Choudry’s story exemplifies the formation of communal ties throughout Harlem, and how among the competition and conflict, Bengali immigrants found ways to survive.

Amir Haidir Khan is another notable figure from this era. Unlike many Bengali seamen, Haidir Khan was not only literate, but he was known for his activity in Indian and American politics. Throughout the late 1910s and 1920s, Khan traveled through the segregated South, to various industrial cities, and American ports. In his memoir, Khan details his observations from these trips regarding other Bengali seamen, describing how they built their lives and forged connections with each other in a foreign country.

Bald writes, “Khan describes his time on and near the New York City waterfront; encountering recruiters and middlemen; working on ships with Indian crews, mixed crews, and white crews; laboring in factories in New Jersey, upstate New York, and Michigan; living with other Indian ‘seafaring men;’ congregating in restaurants, laundries, and rooming houses; attending political meetings in ships’ quarters, hotels, and Baptist churches.” Khan highlights the differences between the lives of seamen and the lives of Indian students and intellectuals in the United States, specifically how no two seamen had the same story.

Eventually, Bengali immigrants got involved with political activism. People like Choudry and Ullah founded multiple organizations such as the Pakistan League of America in 1947. Choudry also advocated for the right to citizenship for Bengali immigrants through his involvement with the India Association for American Citizenship. Choudry even criticized people like J.J. Singh, whose activism for South Asians were usually limited to the elite and upper class.

Throughout their time in Harlem, Bengali immigrants maintained a balance of holding on to their own cultures and assimilating to the environment around them. While many Bengali men fell for Hispanic and African American women purely because their commute to work happened to coincide, other men went out of their way to seek out parties in the Bronx with hopes of meeting more Hispanic and African American women.

This established a stronger relationship between Bengali peddlers and other ethnic minorities in the United States. Interracial marriages and adoption of different cultural practices strengthened the bonds between different ethnic minority groups. This is important to note as anti-blackness and anti-hispanic continues to run rampant throughout the South Asian communities of the twenty-first century. When Bengali peddlers first arrived in the United States, the division between different racial groups was much less pronounced.

Furthermore, as housing projects, economic decline, aggressive policing, and political neglect continue to haunt these ethnic enclaves, we continue to lose the micro-histories of each neighborhood. In New York City, for example, the gentrification of Harlem has forced Bengalis and other ethnic communities to move to other parts of the city or New Jersey’s lower middle class suburbs. In New Orleans, hubs that once flourished as trading centers for Bengali goods were nothing but parking lots, or as Bald puts it, “Wasteland of gravel lots, parked cars, and concrete columns running beneath interstate 10, the raised highway built to direct traffic in and out of the city from its more affluent suburbs..”

As these changes continue to take place at the expense of these various communities, we not only put the rich on a higher pedestal, but we also risk losing the history and legacy of the hundreds of minorities who lived in these areas and survived against all odds.

However, the distinction between the two demographics [Bengalis and African-Americans] only protected the Bengali immigrants to a certain extent. Ultimately, Bengali peddlers and African Americans were tied in the same race for social mobility and equity in American society. As Bald puts it, “The hue of their skin ultimately determined where they return at the end of the day, the type and the quality of the houses in which they would live, the health conditions they would face, and the public facilities they could and could not access, and the risks that attended their daily movements.”

Ayshi Sen is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.' Ayshi loves writing journalistic articles because they allow her to write in a way that is...