When Ableism Starts, and Ends, in the White House

The President’s desire to portray himself as a strong, unwavering leader disconnects him from the people he represents.

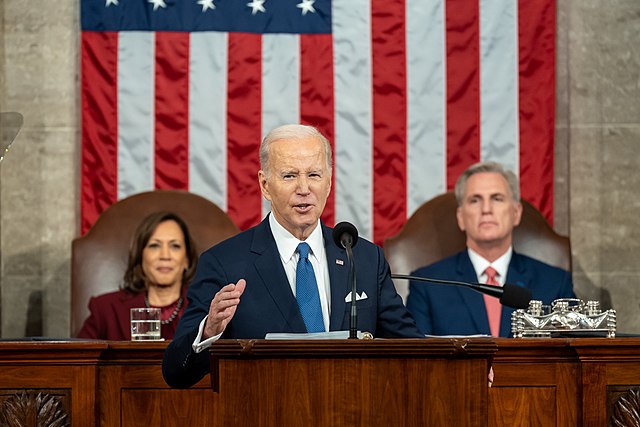

President Biden delivers his State of the Union Address on February 7th, 2023, after spending hours practicing the speech beforehand. Photo Credit: The White House, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

He sits there for hours, rehearsing his speech in his head. He prepares to address a joint session of Congress and the rest of America, writing down notes and dashes in the margins to prevent himself from stuttering.

The pressure is on; not only does he have to make it through an hour-long speech without making mistakes, but he has to reconcile a very partisan legislature and convince the country that the work he is doing is in their best interest.

He’s also setting up his next run for president. While it may not seem worthwhile to invest so much effort into concealing his stutter, in the past, his stutter left him vulnerable to condescending remarks from opponents who weaponized his stutter and claimed it makes him less fit for office.

Joe Biden’s life has long been shaped by his stutter. As a child, he became nervous while speaking in front of his class. He was mocked by his teachers, one of whom called him “Mr. Buh-buh-buh Biden,” and was bullied by other students, which drove him to practice speaking for hours on end so that his stutter wouldn’t be apparent.

Even today, Biden’s stutter remains an issue for many Americans. He faces questions about his mental abilities, an issue that is worsened by his age. “Many people would say Biden’s stutter is among his most visible weaknesses, if not number one,” one journalist, who also has a stutter, says. “But it’s also a source of his strength. It’s also the main source of his grit and his determination, to just be there competing.”

It also serves to better connect him with the Americans he dutifully represents. About one in four Americans are disabled, and three million Americans have a stutter.

Biden is not the first president to grapple with a physical disability. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy all dealt with various disabilities.

Yet for as long as the presidency has existed, presidents have skirted around acknowledging their disabilities, instead trying to conceal or overcome them. Afraid of appearing weak to a population that prioritizes having a strong leader, presidents don’t speak about the challenges their disabilities pose, or even publicly acknowledge them at all.

Lincoln’s disability shaped his life. He lived with depression, which occasionally led to suicidal feelings, and he also experienced debilitating headaches. As president, Lincoln signed a bill that allowed Gallaudet University, a school for the deaf and hard of hearing that today receives significant federal funding, to grant college degrees to its disabled students. Today, the university continues to provide education to deaf individuals, making education more accessible.

Many Americans know of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s struggles with polio, which left him completely paralyzed from the waist down. Yet he hid this as much as possible from the public, placing a blanket or covering over his wheelchair when he was photographed.

He ultimately used his experiences with polio to transform America. In the midst of America’s struggles with polio outbreaks, he founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, which funded polio research and ultimately led to the creation of the polio vaccine.

This vaccine had a huge global impact — according to the CDC, since 1988, over 18 million people can walk today who would otherwise have been paralyzed, and 1.5 million childhood deaths have been prevented as a result of this innovative vaccine. Additionally, no polio cases have originated in America since 1979, and polio is no longer a concern for most Americans.

Today, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis is known as the March of Dimes, a nonprofit organization that focuses on improving maternal and infant health.

John F. Kennedy’s life was also shaped by disabilities; he himself had a learning disability, and his sister Rosemary suffered from mental illness. She received a lobotomy, leaving her physically disabled and changing her personality. While president, Kennedy supported the research and treatment of people with disabilities.

Kennedy became an advocate for the mentally ill; he wanted to pass policies that would help people with mental illness return to society, rather than permanently institutionalize them. He focused on community-based care and the potential for growth, rather than isolation. He ultimately passed the Community Mental Health Act of 1963, which allocated federal funding for community mental health centers and research institutions (note: this legislation had mixed success). Many presidents since then have been inspired by Kennedy’s goals, and have helped further his commitment to helping the disabled.

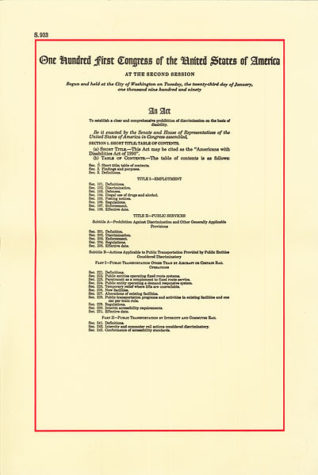

People with disabilities continued to challenge the obstacles that segregated them from their communities throughout the 20th century. They fought for equal rights for disabled people, which led to the creation of the ADA.

The Americans with Disabilities Act was signed into law in 1990 by George H. W. Bush and drastically impacted the lives of millions of Americans. Joe Biden, a senator at the time, recognized the law’s potential to transform people’s lives and co-sponsored the bill. It banned discrimination based on disabilities, allowing disabled people equal access to jobs and education, among other things.

The law shifted society’s view of disabled people; where lack of employment was previously considered a natural consequence of the disability itself, people began to recognize that this was a result of societal barriers that prohibited disabled people from engaging in society in a just way.

Brittany McEntee, who experienced hearing loss as a toddler, spoke of how the Americans with Disabilities Act encouraged people to take her disability more seriously. She said, “when it came to schooling, that’s where the ADA gave us a leg up to say if there were certain needs of mine that weren’t being met. If that was met with any resistance, our requests, then the ADA was something that we had to back up those requests and to say, you know, this isn’t an outrageous request. We’re just trying to close this gap. And it certainly made all the difference.”

So, as President Biden prepared to give his State of the Union address in February 2023, he understood the magnitude of this speech. Although stuttering through the speech would not impact global relations or the economy, it might shake America’s faith in him, because many Americans today see stuttering as a sign of mental incompetency. Yet for the three million Americans at home who do have stutters, seeing a president who doesn’t feel the need to hide his disability, who talks openly and honestly about how his life has been shaped by a stutter, and who stands up and says, without practicing for hours, that people with stutters do not have to change their speech patterns to become president, could be the most encouraging and uplifting thing they hear during his presidency.

Biden has used his time in office to improve the lives of Americans with disabilities. He continues to pass legislation that benefits disabled Americans and hails the Americans with Disabilities Act as an integral part of our nation. In fact, the law was so ground-breaking that it inspired 180 other nations, such as Luxembourg, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom to pass similar legislation.

He does acknowledge that more work needs to be done to secure equal opportunities for disabled Americans. When celebrating Disability Pride Month at the White House, Biden stated that the Disability Rights movement is “about recognizing disability isn’t something broken to be fixed. For millions of Americans, their disability is a source of identity and power.”

He rarely acknowledges, however, that he is part of that group of disabled Americans, and this causes a complete disconnect from the people he is speaking to. If he truly believes that disabilities are a source of strength, if he finds the platform to say that having a disability is not a sign of personal failure, and does not need to be overcome, then why does he spend hours practicing his speeches, concerned that letting his stutter show will impact public opinion?

While society has begun the push towards a more equitable society, disabled people still face discrimination in every aspect of their lives. Ableism continues to constrict the presidency; no American president has, without being prompted, publicly acknowledged his disability. This causes a complete disconnect from the American people, where many people are affected by disabilities.

It’s time to challenge the idea that the President has to remain a strong, unwavering figurehead, and call for change in what we expect from the President. A disability does not make someone weak; it makes them more empathetic, more resilient, and more human. And when that empathy, and that humanity, can be mobilized to drive change that allows for the roughly 61 million Americans with disabilities to experience fuller, more equal lives, we should consider it a failure when the President does not speak up to pass legislation to push us towards the end of ableism.

When celebrating Disability Pride Month at the White House, Biden stated that the Disability Rights movement is “about recognizing disability isn’t something broken to be fixed. For millions of Americans, their disability is a source of identity and power.”

Orli Strickman is an Arts and Entertainment Editor for ‘The Science Survey.’ She seeks to represent stories that do not receive a lot of mainstream...