The Supposed Endgame of the Library

For the past decade, libraries have declined in patrons as readers have opted for digital means of information.

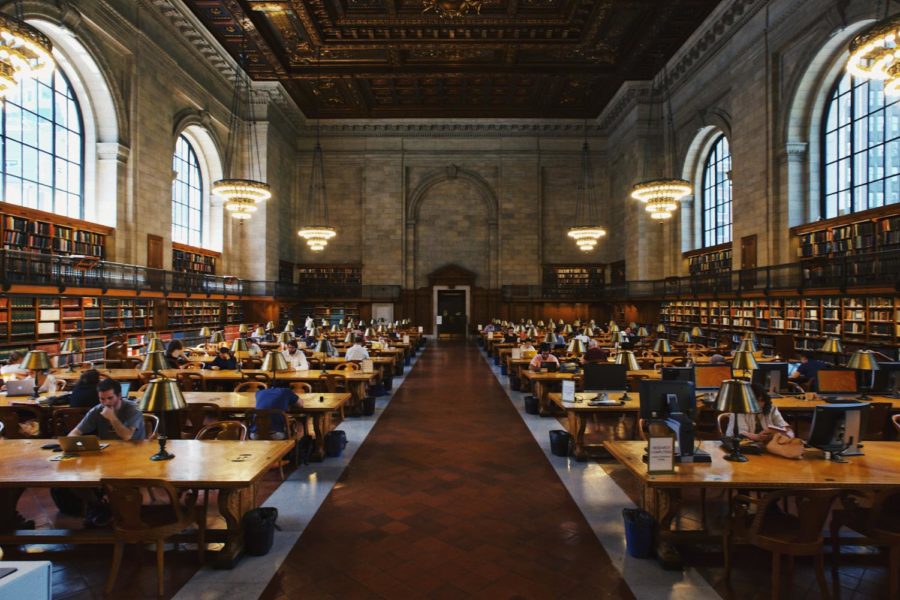

The peaceful atmosphere of the New York Public Library makes it a suitable environment for students to complete their schoolwork.

I can still recall the afternoons I spent after school in the Children’s Room of the Windsor Park Queens Library, buried in the pages of a Thea Stilton book or shuffling through the DVD section for new movies. In an effort to relive old memories (and to replace my stolen library card), I paid a visit to my local library once again this week. Upon entering, I immediately felt a wave of nostalgia as I was greeted with a familiar, woody aroma. However, as I walked farther past the security gates, I realized that the library, once bustling with children and adults alike, was almost devoid of any people.

This is no surprise. Once a staple of community gathering and enrichment, libraries have seen staggering declines in visitors all over the world. The Institute for Museum and Library Services’ Public Library Survey (PLS) reports that in 2009, Americans visited a library 5.4 times per year on average. In 2019, that number dropped to an average of 3.9 visits per year- a 28% decline. Across the nation, the U.S. has seen a fall of 31% in public library building use in the past eight years, up to 2018. Other areas of the world saw similar, if not, worse numbers; both Australia and the U.K saw a 22% drop and 70% drop over the past ten years and 21 years, respectively.

A multitude of factors have played into the decline of library visitors, but the most widely accepted explanation is the rise of e-books. First introduced in 1971, e-books, or electronic books, are published books made or converted into a digital format, designed to be read on an electronic device such as a computer or handheld gadget. This formatting wasn’t popularized until the early 2000s, when companies began developing their first iteration of their e-book readers.

Since then, hundreds of e-reader models have been created, from Barnes & Noble’s Nook to Rakuten’s Kobo. However, their profits pale in comparison to those made by the Amazon Kindle, the most popular device used amongst e-book users. Since its creation, the Kindle has dominated the e-reader market, currently holding 72% of the market share with over 30 million active users in the United States alone.

In 2007, Amazon released their first model of the Kindle: a $399 six-inch E Ink display with a full keyboard and wireless connection over Sprint’s EV-DO network. It gave readers access to 90,000 e-books and sold out in under six hours. This major success would lead Amazon to continue producing different iterations of the Kindle, with there now being a total of six models to date. On September 21st, 2011, the relationship between libraries and corporations would be revolutionized by the release of the Kindle Library Lending, a product of a partnership between Amazon and OverDrive that allowed library users with Kindles to borrow from over 11,000 public and school libraries.

The concept seemed simple; any title a library has available on OverDrive could be downloaded by Kindle users with an Amazon Prime Membership. However, a multitude of problems would arise with its use. When downloading from the Kindle Library Lending, borrowers would not be downloading their library’s copy of an e-book, but instead, a copy directly from Amazon. Even so, the copy would still be listed as “unavailable” on the library’s website, despite not being borrowed from the library.

Borrowers also reported that when checking out e-books, instead of completing the transaction on the library’s website, they would be redirected to Amazon’s website, where they would be prompted to log into their Amazon account. This raised issues regarding privacy, as Amazon was able to track the borrowing habits of their customers. In 2020, Amazon would silently discontinue the Kindle Library Lending for its Prime Reading program, leaving both libraries and readers with little to no explanation.

Amazon would continue to meddle with library affairs, beyond just e-books. In 2019, Audible, a subsidiary of Amazon, pursued an exclusive deal with Blackstone Audio that would deny public libraries access to newly released audiobooks for 90 days. By doing so, library patrons would be more inclined to purchase audiobooks from Audible instead of waiting a full three months to access a new release from the library.

In response, dozens of libraries across the country joined together to boycott Blackstone, along with other audiobook producers such as Simon & Schuster, Macmillan, and Hachette, for six months. News of the boycotts spread to media sites and library publications, reaching as far as those based in France and Australia. However, despite the media coverage and negotiations, Blackstone Audio has yet to give a clear public statement on the matter as of July 2019.

So how are traditional public libraries competing against tech giants and unjust publishing companies?

Despite issues with previous partnerships, libraries have continued to collaborate with other apps and services to deliver easier access to collections of digital material. “There’s an app called Libby that I use now instead of the New York Public Library, since I rarely visit the library due to my busy schedule,” said Aaron Tang ’23. “You download the app, enter your library card details, and access a vast collection of ebooks and audiobooks- there’s still a borrowing limit, though, since it’s partnered with libraries around the world.” One drawback of Libby is that only public, corporate, or academic libraries can be found on its app. However, this should not pose any issues for the standard library patron.

Many libraries have also created their own mobile services, such as the Queens Public Library Mobile App and New York Public Library App, which aid in checking out digital and physical materials, registering for classes, and presenting catalogs of available books. These were extremely successful in keeping community engagement, especially during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Although visits with intent to borrow physical material have dropped sharply in recent years, it has been rising in terms of program participation. In 2019, 125 million Americans participated in one of the six million library-held programs available for people of all ages. It is estimated that one in every ten people have attended a program held at their local library.

Nonetheless, these digital advancements have come at a cost. The majority of US public libraries have cut almost 50% of their physical copies of books, magazines, and audiotapes and converted around 40% of those materials into a digital format. However, these conversions have increased registered borrowers and the number has been consistently growing since 2006; as of 2019, there are 174.23 million registered borrowers in the US. 58.75% of the total U.S. Public Library collection is now digital.

Still, even with the increasing popularity of e-books, print books have remained the most popular reading format. Although e-readers provide far more convenience and portability than physical books, they lack the essence of holding a book and flipping through its pages, a fundamental experience many love when reading. One could say this advancement has detracted from the foundations of readership.

The shift from paper books to e-books is an inevitable result of the digital age. With information being readily online anytime anywhere, the need to physically visit a library has diluted, especially with the demanding schedules of students and workers. “Like all transitions, there are still pros and cons to the declining use of libraries and digitization of content,” Tang said. “But in terms of providing convenience to people who frequently commute or can’t always set aside a few hours every week to visit the library, I would say I’m all for it.”

This is only a piece of the bigger picture of how technology has changed our methods of obtaining information; after all, we’ve been living in the digital age since the 1980s. You may have forgotten things like newsstands, magazines, or even paper maps. Whether these shifts are positive or negative can vary depending on the lifestyle one has led as a reader. While my busy schedule allows me less time to frequent the library compared to my younger years, I take comfort in the fact that the library remains a haven where I can unwind and browse through thousands of books.

Once a staple of community gathering and enrichment, libraries have seen staggering declines in visitors all over the world.

Chelsea Li is an Editorial Editor for 'The Science Survey' and reviews and edits articles published in this section prior to publication. She finds that...