Get Your Work Done! The Perpetual Pitfalls of Procrastination

In the need to complete every task “just right,” procrastination can be a comforting distraction… before it begins to affect one’s quality of work and mental health.

In the self-defeating snare that is procrastination, motivation and initiative feel intangible until there is no choice but to succumb to approaching, immovable deadlines.

“You may delay, but time will not.” Benjamin Franklin, prominent writer, politician, and entrepreneur, was known to condemn poor time management. Clearly, Franklin had no concept of the modern American high school, or he would have understood the sweet gratification from submitting an assignment at exactly 11:59 P.M. after being certain you would not finish. He would have understood the rush of adrenaline, the reward, and the utter overwhelming nature of the teenage schedule that bars earlier action.

Understanding Procrastination

Procrastination, which means to delay or postpone something, is fundamental to understanding the struggles of modern adolescence. The American Psychological Association (APA) noted between 80-95% of college students procrastinate. Furthermore, 75% identified as “procrastinators,” and roughly 50% claimed to procrastinate in a “consistent and problematic manner.”

This may be because, as Cece Beauchamp ’25 explained, “I have little to no motivation to do work.” Kenae Taylor ’24 provided a different justification: “Laziness, or mental health isn’t allowing me to get started.”

In some reports, procrastination occupies more than one third of students’ time in a day. It is a coping mechanism, a temporary source of mood management, and a dangerous form of distraction.

As one study found, metacognitive awareness (M.A.) – being conscious of how one thinks and processes – and educational stress combined strongly affect the likelihood of academic procrastination. There is a significant positive correlation between educational stress and procrastination, meaning greater procrastination under more difficult circumstances.

Conversely, a significant negative correlation exists between academic procrastination and metacognitive awareness, meaning as one grows more attuned to their own thoughts and neuroses, the less they procrastinate.

Turkish procrastination researcher Dr. Saadet Aylin Yağan explained, “Many variables can affect procrastination. The level of importance given to the task, personality characteristics (being lazy or hasty), mood, demographic and cultural variables are among the most important ones.” People who possess characteristics of distractibility and impulsivity tend to be more likely to procrastinate.

She continued, “Cultural characteristics and family structure are very important factors [in defining procrastination]. For example, some families in Turkey (or different countries) may prefer their children to get a job rather than academic advancement (economic or social reasons). This may cause students to attach less importance to academic tasks and thus exhibit more procrastination behavior. Another factor is gender discrimination. In different cultures, opportunities are offered to the academic progress of male and female students may not be equal. These and other cultural differences are worth investigating through comparative education.”

Across cultures and backgrounds, however, there lie many constants. According to Dr. Ferrari of the DePaul University in Chicago, procrastinators tend to fall into three main categories: arousal types, avoiders, and decisional procrastinators. The aforementioned adrenaline-seekers yearn for the high stakes of approaching deadlines. Avoiders are consumed by social perception, afraid to fail or appear incompetent. The final category is made up of those paralyzed by decisions who instead choose to not make any.

Procrastination can also vary depending on the task. In one study of college psychology students, although only 10% procrastinated on general school activities, 46% tended to procrastinate on term papers. It was determined that as the stress and weight of an assignment increases, so does the likelihood of procrastinating.

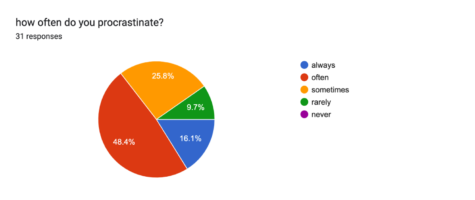

At Bronx Science, a cross-grade survey of thirty-one participants using the Solving Procrastination scale found that 87.1% of participants continually iterate “I’ll do it later,” 67.7% would not get started until the last minute before their deadlines, and 80.6% would stall starting “unappealing tasks.”

Carys Chan ’25 stated, “I just want to feel mentally prepared to start doing work but I never do.” Avoiding unpleasant assignments prevents the corresponding unpleasant emotions. After all, why would someone willingly engage in the less enjoyable activities and decrease their mood?

The Negative and Mind-Altering Impacts of Procrastination

Procrastinating is not without its dangers. As psychology professor Fuschia Sirois stated in The Guardian, “Embedded in the definition of procrastination is that you unnecessarily and voluntarily delay an important intended task despite knowing that the consequences are harmful. How can that be positive?”

When we procrastinate, we dismiss stressors and feel a brief peace, until failed emotional regulation increases the magnitude of our issues. Procrastination represents present bias, our propensity to concentrate on the immediate at the serious expense of the prolonged.

When a task causes anxiety, the amygdala interprets it as a threat and works at all costs to avoid managing it, causing the “amygdala hijack” and the willingness to do whatever necessary to avoid danger, no justification necessary. The larger circumstances do not register until far later… and too late. Dr. Hal Hershfield found that, neurologically, we tend to dissociate with our future selves, regulating these later tasks – and the negative consequences – to seemingly someone else entirely.

Procrastination is inherently tied to mood management. One survey discovered 94% of people believed procrastination negatively affected their happiness. It increases anxiety, guilt, self-blame, low life satisfaction and shame. It can even compromise immune systems, causing hypertension, insomnia, headaches, and heart issues along with colds, flu, and gastrointestinal issues and chronic illness.

Procrastination has also been tied to greater rates of alcohol consumption. A type of avoidant coping mechanism, the inability to stop drinking reflects one’s failed self-regulation, which is also what allows even those with the best of intentions of completing work to stall and disengage.

Furthermore, it has been negatively correlated with all facets of academic performances, from GPA to assignment performance to even final exams. Professor Kathy Green found in 1997 that procrastination was one of the lead causes of doctoral students failing to finish dissertations. A German study found that those who admitted procrastination were more likely to partake in academic misconduct, such as faking excuses for gaining extensions, plagiarism, and cheating.

In team dynamics, one’s personal procrastination can force other group members to take on more responsibilities, causing resentment and unbalanced power dynamics. Furthermore, teachers frequently penalize late or procrastinating students; one 2015 study found that, for business school students, the more time they waited to submit assignments, the lower their grades were, with eleventh-hour submissions losing them roughly 5 points on average.

In the Bronx Science community, the aforementioned student-conducted survey found that 61.3% constantly delayed improving work habits and 64.5% put off decision making.

Time management practices and self development patterns solidify over adolescence, so the creation of harmful habits can span a lifetime if not caught.

This extends beyond the academic sphere: to lessened job security, limited career futures, unemployment – with procrastinators making up nearly 60% of the unemployed – and lower salary.

Not all of the consequences of procrastination are external. With time, regions of the brain that connect to threat detection and emotional regulation develop differently in chronic procrastinators. Procrastination can quite literally change brain chemistry.

When pressure overwhelms, sometimes delaying is the only way to cope. It is also a built-in excuse for bad performance, the self justification that one simply failed because they “ran out of time.” Thus, one’s ability – thereby identity as a student or professional – is not connected to one’s sub-par work. This is also known as self-handicapping, procrastinating while blaming failure on timing, or self-sabotaging, consciously or unconsciously procrastinating as a way to prevent goal accomplishment.

To Binah Friedman ’24, the most overwhelming aspect is, “When the work piles up and there are like five different things I need to do before I go to bed, and I start thinking about all of them at once and then I can’t do any of them.”

Meanwhile, others claim to love the rush of adrenaline found in last-minute work. However, this tends to ring true in the time leading up to the deadline, not the last few hours themselves, which are riddled with anxiety, stress, pure exhaustion, and the overwhelming fear of imminent failure.

As Princeton Professor Dominic J. Voge stated in his Classroom Resources for Addressing Procrastination, “For the most part, our reasons for delaying and avoiding are rooted in fear and anxiety-about doing poorly, of doing too well, of losing control, of looking stupid, of having one’s sense of self or self-concept challenged. We avoid doing work to avoid our abilities being judged. And, if we [happen] to succeed, we feel that much ‘smarter.’”

Mental health conditions also exacerbate procrastination tendencies. People with lower self-esteem tend to procrastinate out of self-doubt. Those who exhibit perfectionism may stall until they are sure they can write at the sufficient level to satisfy their internal narrative. Procrastination is further associated with increased anxiety and depression.

Modern society has also not helped procrastination tendencies. With the surge of online work and the decreasing strictness of deadlines, people have developed lasting, harmful habits. As Yağan reflected on her own lectures, “I can say that there has been an increase in students’ procrastination behaviors especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of students who did not complete the assigned tasks or requested additional time increased.”

Strategies for Overcoming Procrastination

Procrastination is not a set future, but change must come with awareness, adaptability, and motivation. First comes the processing of procrastination, understanding the need to recoil from responsibility. This may be realizing that procrastination prevents feelings of insufficiency. Just naming the underlying struggle helps people resist the temptation to procrastinate.

Yağan advised, “Some strategies I can suggest to students: recognizing their strengths and weaknesses, realizing how they learn best, finding ways to make tasks more interesting and fun, and discussing why and how the academic tasks are important for them.”

Moreover, time-management techniques that assuage stress while enforcing the importance of tasks tend to work best in managing procrastination.

It is also important to acknowledge that not every resource works for every person. While I love my planner and the sweet relief of checking off boxes from tasks completed, an overwhelming amount of assignments consolidated in one place may only leave someone else defeated and returning to old habits. So, remember to be flexible with yourself. Reward yourself. Allow for reasonable goals. Break the uncontrollable into smaller, achievable tasks.

As Samit Chowdhury ’23 added, “I just try to make a list of things I need to do and just sit down and try to slowly chip away at the list.”

Stay motivated! Hard work takes time. Remember your dreams, your hopes, not the fear, not the imposter syndrome, not the spite. Use goal-setting charts and refer to them often. Be engaged and raise your hand. Push yourself to find what is interesting. Reflect on your habits and feelings, work bit by bit, immerse yourself in conducive settings, and be kind to yourself.

One inherently simple but overlooked tactic is self-compassion. When we treat ourselves with understanding of mistakes rather than hatred, we increase motivation. We reduce psychological distress, a key factor for procrastination, increase feelings of self worth, and foster optimism, personal initiative, and curiosity. Forgiving oneself changes everything. A study at Carleton University found that students who forgave themselves for procrastinating studying for an exam were able to procrastinate less on their next one. By ridding oneself of judgment, productivity rapidly improves.

Additionally, focusing on immediate benefits rather than future costs – a hallmark of procrastination logic – is a concept called “time inconsistency” which has tangible solutions. First, one can make longer-term choices feel more inviting or concerning by visualizing the future outcomes. Imagining the blissful freedom of a lighter workload or the frightening onslaught of missing assignments can jar a student into working harder and sooner. If not enough, external deadlines can help provide a sense of urgency as can a physical sign.

Additionally, removing procrastination triggers from one’s life makes a monumental difference. For instance, procrastination has also been linked to internet use, namely through television and video games, so using mediums like AppDetox, Canopy, Saent, and Freedom that monitor and restrict screen time can be highly effective. Without the distractions, there is no choice but to get work done.

Charlie Kerr ’26 advocates this effect: “I do my homework when there is nothing to do except for my homework. I don’t have many addictive apps on my phone (my own choice) to allow myself to not turn to my phone whenever I am bored.”

Even certain music, such as classical and instrumental, that does not require much concentration to listen can improve focus. Being relaxed lessens the panic surrounding an assignment.

One can also find an accountability buddy – aka “Accountabilibuddy” – a relationship where both people make sure the other follows through on commitments. Not feeling alone with one’s thoughts can do wonders for productiveness.

For those who struggle with procrastination as a part of deep-rooted mental health struggles, there are also clinically-approved possibilities. For example, people with depression may struggle to plan for the future or find the enthusiasm to begin an assignment, so using behavioral activation, a cognitive behavioral therapy tool that schedules enjoyable activities that yield a feeling of proficiency or achievement, may provide relief.

Fixing ingrained habits takes time and energy, but such is true for all worthy aspects of life. To return to Franklin, who may not have known the modern academic landscape but definitely held lasting wisdom, “Without continual growth and progress, such words as improvement, achievement, and success have no meaning.”

Procrastination is not a set future, but change must come with awareness, adaptability, and motivation. First comes the processing of procrastination, understanding the need to recoil from responsibility. This may be realizing that procrastination prevents feelings of insufficiency. Just naming the underlying struggle helps people resist the temptation to procrastinate.

Hallel Abrams Gerber is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey,’ using her writing to represent a myriad of social issues and innovations, bolster...