The Fight Greater Than Just A Gem: The History of the Kohinoor Diamond

Who should own the Kohinoor diamond, India or England?

AlinavdMeulen, CC BY-SA 4.0

Here is a replica of the crown of the Queen Mother, along with a replica of the Kohinoor diamond, a centerpiece at Royal Coster Diamonds.

History is a two sided coin. Each individual has their own interpretation of past events, which is sometimes based on unfounded claims, especially if there is no written evidence or photographs to prove their claims. The Kohinoor gemstone has a story based on claims and history that can neither be proven by documents or photos. The Kohinoor’s origins still remain a mystery, but we do know its history during the past century.

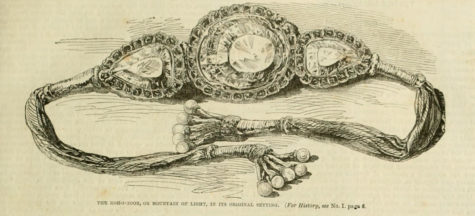

The meaning of Kohinoor, a precious gem, is ‘mountain of light,’ and while its exact origins are unknown, it was believed to be discovered in South India in the 13th century. It was originally about 186 carats. Over many centuries, the Kohinoor diamond was handed over to several dynasties, beginning with the Mughals in the 16th century. Following this came the Persians, and then the Afghans, before settling with Sikh Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1813. The Kohinoor gemstone that we know today is a product of these dynasties and the British Raj.

The British Raj is the reason behind the current fate of the Kohinoor. When reminiscing about India’s history, the years from 1757 to 1947 recounts a story that many do not remember or of which they are unaware. The story regarding how the Kohinoor landed in the hands of the British starts with how Britain became rulers in India. The story begins when the British disguised themselves as mere traders. As a result, when they attempted to claim land for themselves, they were met with resistance. Previously, the British had a cordial relationship with the state of Bengal. However, when the soldiers of the East India Company became more aggressive towards the Bengalis, the feeling was reciprocated. In spite of that, heavy rains led to the failure of defending their land. The Bengalis were unable to cover the gunpowder for their cannons, unlike the British who did so seamlessly.

However, the Kohinoor has a history that precedes the British Raj in India. When Nader Shah of Iran raided Delhi in 1739, he began the history of the unknown true owner of the Kohinoor. Following Shah’s death, it fell into the hands of his general, Aḥmad Shah, founder of the Durrani dynasty of Afghans. His descendant, Shah Shoja, had possession of the Kohinoor, but was forced to surrender it to Ranjit Singh, the Sikh ruler, after becoming a fugitive in India. After the death of the Punjabi ruler, Ranjit Singh, his son, Duleep Singh became Maharaja Duleep Singh and therefore inherited the Kohinoor.

Maharaja Duleep Singh, the son and successor of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, had held onto the gem until Britain’s annexation of Punjab in 1849. Duleep Singh, being only eleven years old at the time, signed the Treaty of Lahore, forcing him to give up the Kohinoor to the British throne. The Treaty of Lahore was signed on March 9th, 1846. The treaty forced the Sikhs to hand over Kashmir and Hazara and Jalandhar Doab to the British. It was due to this treaty that the Kohinoor diamond was handed to the British. Lord Dalhousie, a Scottish statesman and governor-general of India twisted matters to make it seem as though the Kohinoor was a ‘gift’ to Queen Victoria.

The jewel was incorporated as the central stone in the queen’s state crown by Queen Elizabeth, consort of George VI, at her coronation in 1937. The Kohinoor diamond continues to remain a part of the crown.

Although the British have created customs and traditions by adding the Kohinoor diamond to its ceremonies, many Indians believe that the British are not its rightful owners. Like the French who looted Egypt, the British coerced Indians into providing them with their precious belongings. The difference is that the French returned many of the illegally acquired items during their occupation, unlike the British. Many Indians believe that the British should follow the lead of other countries and return all of the stolen artifacts.

The Kohinoor diamond’s history gets even more complicated because many people believe that the Kohinoor was cursed. It is rumored that any man who wore the diamond would experience great misfortune, or that it is spiritually saturated with the bloodshed of historical conquests. Because of the rumors, the Kohinoor initially never became a star of the royal gem collection. Worn occasionally as a brooch by Queen Victoria, it was eventually set in the crown of Queen Alexandra and then in that of Queen Mary. In 1937, it was refashioned as the central diamond on the crown of Queen Elizabeth.

Some believe that the rumors should be enough to convince the British to hand over the Kohinoor. However, the British argue that the gem is as much a part of their history as that of the Indians. Indians, on the other hand, maintain that the lack of a Queen Mother means that the Kohinoor is of no use to the royals or to the country itself. The current British reign and heirs are all male. The current King and princes will have no use for this crown or the jewel that it holds because they have no purpose of wearing it.

The lineage of British royals and their gender has led to a petition. On LinkedIn, Venktesh Shukla, the founder and managing partner of investment company Monta Vista Capital, created a petition to return the Kohinoor to its rightful owners, the Indian Government. Shukla’s petition recounts the journey of the Kohinoor from its mining to the hands of British Royals, and he’s hoping to get one million people to sign onto his cause. In an effort to maintain neutrality, he labels the United Kingdom as an honorable country. But, he mentions that the honorable action, therefore, is to return the “loot” to where it truly belongs. Additionally, Shukla said, “The British should return the Kohinoor diamond to India now. Every time the crown appears with the Kohinoor, it reminds the world of Britain’s colonial past and the shameful way they got a child prince to “gift” it to Britain.”

The manner in which the Kohinoor was acquired is a reminder of a time in India where Indians lost their voice. The Kohinoor diamond still being in the hands of their oppressors is a constant reminder of the power play that existed between India and the British Empire.

The British royals have yet to respond. Unless they respond that they will never return the Kohinoor, many Indians will continue to utilize petitions and Twitter as mechanisms to relay their opinions regarding this issue. Kishan Dey ’24 believes that this petition is nothing more than a petition started by the public that will end in no demands being met.

Asking for the return of the Kohinoor is not surprising, considering that the British have agreed to return items looted by the British soldiers from Nigeria. A museum from London is returning a Benin Bronzes collection ransacked back in the late 19th century from Nigeria. The Horniman Museum and Gardens in London is transferring a collection of 72 items to the Nigerian government. This decision comes after Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments formally asked for the artifacts to be restored earlier this year following a consultation with community members, artists, and schoolchildren in Nigeria and the U.K..

The Horniman’s collection is a small part of the 3,000 to 5,000 artifacts taken from the Kingdom of Benin in 1897 when British soldiers attacked and occupied Benin City as Britain expanded its political and commercial influence in West Africa. The British Museum alone holds more than 900 objects from Benin, and National Museums Scotland has another 74. Others were distributed to museums around the world.

The artifacts include plaques, animal and human figures, and items of royal regalia made from brass and bronze by artists working for the royal court of Benin. If a multitude of items were able to be returned to its rightful owners, Indians pose the question, why can’t just the Kohinoor diamond, which is one artifact, be returned?

Countries including Nigeria, Egypt and Greece, as well indigenous peoples from North America and Australia, are demanding for the return of artifacts and human remains amid a global reassessment of colonialism and the exploitation of local populations. As Swarnali Paul ’23 said, “India’s request is not unusual, but it does need further backing from the official government to substantiate the wants of the public.”

The manner in which the Kohinoor was acquired is a reminder of a time in India where Indians lost their voice. The Kohinoor diamond still being in the hands of their oppressors is a constant reminder of the power play that existed between India and the British Empire.

Niha Roy is a Managing/Advisory Editor and a Staff Reporter for ‘The Science Survey.' She enjoys writing articles about issues and groups of people whom...