America and the Slow March to Republicanism

Americans took a turbulent journey from 1776 to the political climate we work within today.

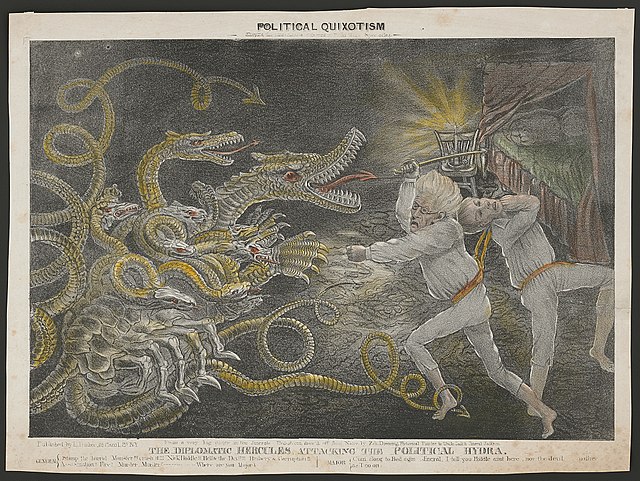

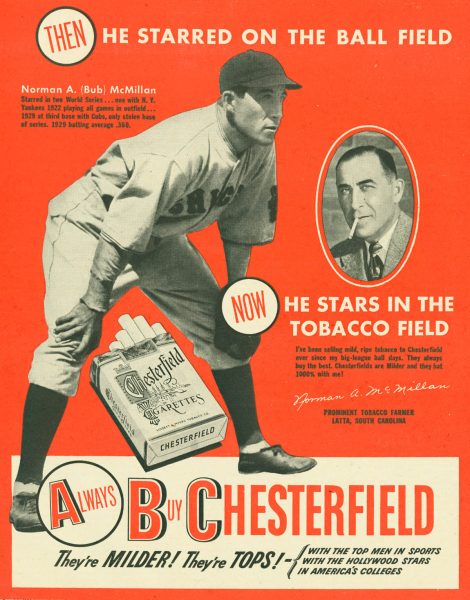

Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Jackson fought an overzealous U.S. banking industry, culminating in his final stand against federalism. Here, he is depicted in a contemporary illustration, as having a nightmare and fighting a hydra representing U.S. banks.

When fur merchant Thomas Willett and Richard Nicolls marched into the prized Dutch territory of New Amsterdam, Willet was waving a white flag, not in surrender, but as an offering.

Months earlier, the Dutch had announced plans to sign the land away into English control, but with suspicions of burgeoning resentment, Charles the First sent a handful of diplomats along with the deed to make sure the deal went according to plan. Eventually, after many threats of violence, the deal went through, and Willett signed his name, catapulting him into the convoluted role of mayor of New York City.

Since Willett, the job of New York City mayor has evolved into a far larger responsibility. New York is the largest city in the country, with the largest GDP estimated at 1.8 trillion dollars, equivalent to that of the entire country of Canada. As Willet passed down control, New York just kept growing. Boasting a massive coastline, the city was able to transform itself into an imposing trading port for the thirteen colonies, eventually surpassing the colonial jewel of Philadelphia in 1835.

Only a year before New York City beat out Philadelphia for the top spot, mayors began to be elected by direct popular vote. Prior to the Charter of 1834 – a section containing an amendment that put the power back into the hands of the people – elections were chosen by an elected council. Prior to the council, mayors had simply been appointed by the Governor.

So when white men and the slim portion of property-owning black men of New York finally got the opportunity to exercise their well earned freedoms, they voted for Cornelius Van-Wyck Lawrence. Lawrence was initially a state senator known for changing his vote on any particular bill on a whim, typically according to his personal financial consequence and for his bizarre tendency to cry at the stand, usually overcome by his own argument and its presumed passion. The city was generally ambivalent to the senator, and after serving only a year in office, Lawrence decided it was time to try his hand at the newly constructed position as commander of the city.

Thankfully for Lawrence, voters weren’t principally concerned with individual policies or belief, but rather the struggle for national leadership between the Jacksonians and the Whigs. Lawrence and his opponent Gulian C. Verplanck served as stand-ins for the national ballot, with Lawrence representing his fellow democrat Andrew Jackson, and Verplanck representing the general conservative resentment around Jackson’s closure of the National Bank.

Dr. Todd Davis, an instructor of the American Studies program at Bronx Science, qualified that voters across America were passionate about party lines, especially when Jackson was at the top of the ballot.

General perceptions carried Lawrence to office, as he etched out a win by a margin of less than 200 votes. Lawrence accomplished little of note in office, aside from putting down an inauguration day riot of about a thousand aggrieved Whig voters, eventually resigning just three years later in 1837.

New Yorkers were puzzled, why had they exerted their newfound voting power to elect the tearful state senator? The answer lay in the complex party system that Americans found themselves in, with Andrew Jackson at the wheel.

Prior to the War of 1812, America was largely divided among the Democratic-Republicans and Federalists. As the nation eventually turned its curious eyes back onto the international front, it was met by the hurricane of Napoleon-era Europe, which would eventually contort its two-party system into a deeply warped arrangement of government. The turn began as England encroached further and further into American sea, impressing American sailors who were trading with English challengers in Europe, consequently cutting off America’s massive trade routes. Eventually as losses piled up, President Madison declared war in June of 1812 in what he thought to be the first step of the final battle over American independence.

The war began with a vote of 19 to 13 in the senate and 79 to 49 in the house. Federalists, who were generally against the war, sat opposed over fears of claiming Napoleon as an ally and the heavy toll that the war would exact on a young nation. But with the slender majority, the Republicans prevailed, winning major battles early on, as Federalist opposition seemed more and more illogical. Quickly, the vocal Federalist opponents seemed like traitors for ever being weary of American idealism, and accusations of British loyalty eventually brought the party to its knees as it collapsed in the early turn of the 19th century.

With no limits on their own power, Republicans nominated 4 total candidates: William Crawford, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, and John Adams. Crawford, former Secretary of State under James Monroe, won a slim margin of the vote along with his fellow Southerner, Henry Clay. Jackson, after being nominated by Tennessee’s state legislature and, at first, declining – claiming he would rather retire to his farm – eventually joined the race, winning 41% of the vote. He was trailed by John Adams, the eldest son of John Adams and a longtime congressman and ambassador, who was at a measly 30%.

With no candidate reaching over 50% of the vote, the decision went to the house who, after intense bartering and lobbying, begrudgingly awarded Adams the White House. Adams won largely due to his former opponent Henry Clay who, defying arguments from Kentucky (his home base) state legislature, made the push against the late-stage Jackson momentum. Jackson returned home to Tennessee defeated, yet largely accepting of the larger democratic choice, even going as far as to congratulate Adams at a dinner party held the night after the election.

But Jackson quickly realized he had been duped. In victory, Adams named Clay as his official secretary of state, plainly laying the path towards a Clay presidency. Jackson saw the move as blatant confirmation that his campaign was a victim of the elitist remnants of the Federalist party he had worked to root out. The cordial path was no longer an option for Jackson. He first made sure that his allies in the house knew to kneecap any proposals Adams would go on to introduce during his four-year term, then he got to work making his case to the American people once more.

As Jackson traveled across the nation aggressively campaigning that he was the man for the job, his allies in the senate began making clear their animosity towards Adams. An ambitious agenda containing proposals like a national university, naval academy, and the introduction of the department of the interior was squashed effectively. After a monotonous four years, Adams met real political turmoil with Andrew Jackson and his supporters who went by the Democrats or simply the “Jackson Men.”

Jackson, significantly boosted by the rapid democratization of the electorate, was hoisted up by some Americans who had grown incredibly discontent with the slow, virtually absent American growth and the turning tides of power leaving the hands of states into the federal government. Ultimately, however, Jackson did not need strong command of policy or even strong opinions on the issues that preoccupied much of the country; instead he relied on his pre-established reputation and the country’s sheer hatred of the Adams administration. These two chief components of Jacksonian politics demonstrated clear superiority, winning him an overwhelming victory of about 100 thousand votes (on the electoral front, Adams couldn’t even crack 100, at 83 votes compared to Jackson’s 178).

When Jackson entered the White House, he was eager to demonstrate a distinct atmosphere from the past administration. To do this, he first held a raucous inauguration party filled with political allies and friends; the party was eventually breached by particularly excited Jackson supporters who only left once the White House appeased them with bottles of liquor and fruit juice. Secondly, and more importantly, one of Jackson’s first acts as president was to launch an investigation into Adams-era fraud and embezzlement.

Jackson would go on to tank the economy, create mass division within the senate, and veto the house’s majority a total of twelve times. Despite a turbulent run, Jackson left office in 1836 with his reputation intact, lifting Democrat Martin Van Buren into office and starting a string of Democratic dominance (aside from two notable Whig exceptions, one of which died less than a month into office). Democratic rule held a solid grasp on American voters up until the Civil War induced party switch and the larger turn against slavery across the nation, but Jacksonian politics have made a contemporary comeback.

Partisan throwaways, violence towards voters, and accusations of corruption and elitism across the aisle have all reentered the modern politician’s playbook (some will even draw the comparison themselves). Jackson demolished republican values and proposed his own archaic ballot in their place, incentivizing voters to vote down party lines and fulfill their duty as Jackson men.

Jackson, significantly boosted by the rapid democratization of the electorate, was hoisted up by some Americans who had grown incredibly discontent with the slow, virtually absent American growth and the turning tides of power leaving the hands of states into the federal government. Ultimately, however, Jackson did not need strong command of policy or even strong opinions on the issues that preoccupied much of the country; instead he relied on his pre-established reputation and the country’s sheer hatred of the Adams administration.

Griffin Weiss is an Editor-in-Chief of The Science Survey and enjoys writing about arts and culture. The most interesting aspect of journalism for Griffin...