Spring Forward, But Don’t Fall Back: The Proposed End of Daylight Saving Time

Daylight Saving Time has been an institution in America for decades, but some people want to abolish it.

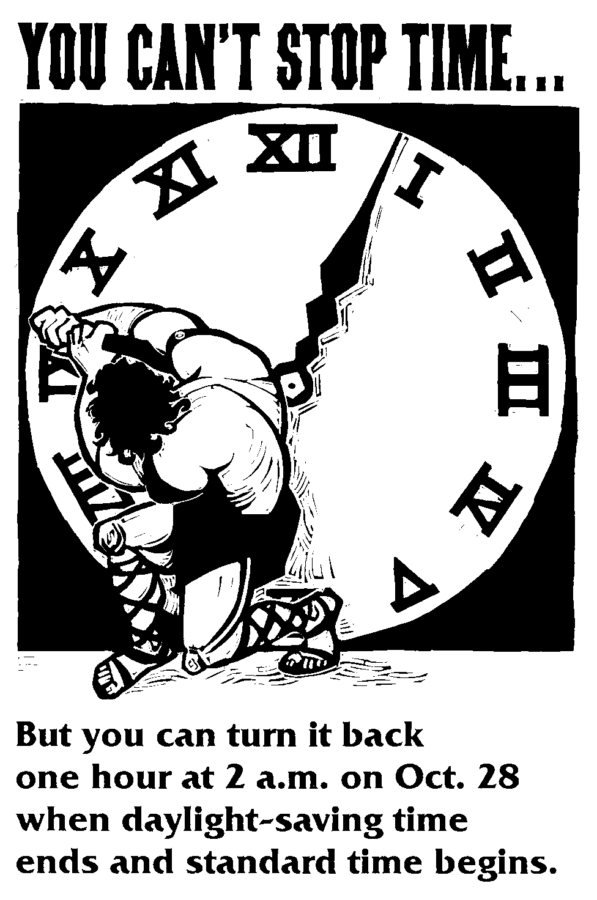

United States Department of Defense, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Here is a poster made by the United States Department of Defense in 2001 explaining Daylight Savings Time. When this was published, DST ended on October 28th, instead of on November 6th as is standard practice today.

When you wake up, the sky is dark, the birds have yet to start chirping, and the air is cold. It’s 6 a.m., maybe 6:15 if you’re lucky, maybe 5:30 if you’re not, but under the blue-black sky it might as well be midnight. As you walk to the train, you think back longingly towards the summertime, when the sun rose at 5 a.m. and you woke up to a warm, bright, welcoming world. Or maybe you’re looking forward, to 1:59 a.m. on Sunday, November 6th, when a minute passes, your clock falls back, and it’s 1 a.m. again. When Daylight Saving Time ends for the year, the sun rises earlier (or are you just rising later?), and you wake up to a lighter sky.

Daylight Saving Time (DST) has been an institution for longer than many people have been alive. You grew up learning to “spring forward, fall back” by manually resetting each clock in your apartment, and then you bought a smartphone to spring and fall for you. Now time jumping back and forth is as normal to you as the flowers blooming or the leaves turning red. But DST isn’t as timeless as it seems; it was only signed into permanent law in 1966, and it hasn’t been fully adopted across the United States. If some Congressmen have their way, DST won’t be around for much longer.

The Sunshine Protection Act, which has been approved by the Senate but not by the House Representatives, would make Daylight Saving Time into the new standard time, eliminating clock change permanently. This would protect the long, sunlit summer evenings granted by “springing forward” but usher in a new era of dark, cold winter mornings, without any hope of “falling back” and regaining some sunlight.

DST has been around in some form since the Roman Empire. Instead of having hours of a fixed length, ancient Romans divided the amount of daylight into twelve equal portions, and called each portion an hour. This system naturally included daylight saving, since it accommodated days with different amounts of daylight. For example, if school always started at the second hour, then it would always start after the sun had risen, even on days when the sun rose later. Since ancient Roman hours were always considered relative to sunrise, they were able to keep their listed times the same, even as the absolute time varied.

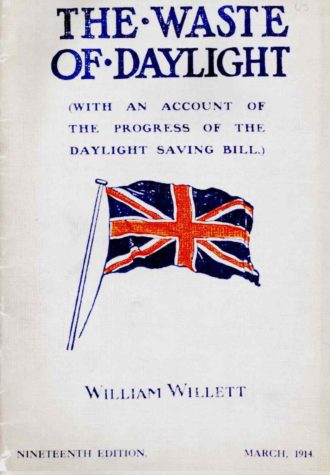

The first serious modern proposal for DST was written in 1895 by an entomologist named George Vernon Hudson. He wanted to shift time two hours forward in the summer in order to enjoy long summer evenings. While the idea was initially unpopular, some found it appealing, and decided to build on Hudson’s work. In 1907, an Englishman named William Willet proposed shifting time forward by 20 minutes at 2 a.m. each Sunday in April and back by 20 minutes each Sunday in September to save on electricity costs. This scheme shared some similarities with our modern system, but required people to reset their clocks four times a season, instead of just once. Parliament considered his proposal but ultimately decided not to pass it.

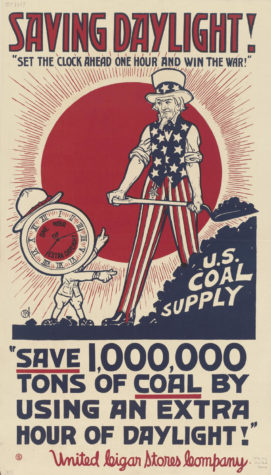

However, Parliament switched to DST just a few years later. World War I had started and Britain was eager to save fuel. Many other countries, including Austria, Germany, and the United States, followed suit. Governments tried to portray adopting DST as a patriotic act and a part of the war effort, but this approach also inextricably linked DST with war in the minds of the public. Consequently it was mostly abandoned shortly after the war ended. In America, DST was once again adopted and then repealed during World War II.

In 1966, Congress passed the Uniform Time Act, which established DST from the last Sunday in April to the last Sunday in October. However, the Act allowed states to opt out of DST, which Hawaii and Arizona did. DST has since been changed to begin on the second Sunday of March and end on the first Sunday of November.

Many politicians have challenged DST over the years, and members of Congress have introduced bills to repeal it every year since 2018, without success. However, since 1966, DST has only been repealed once, and that decision was a complete failure. It was 1973, President Nixon was in charge, and the United States was dealing with an oil embargo and the devastating climb in energy prices it caused. Once again, Congressmen suggested repealing DST to save fuel, and everyone was so desperate for a solution that they decided to try it. The subsequent winter of dark skies and traffic accidents caused fierce public outrage, and in October of 1974, the normal “spring forward, fall back” schedule was restored.

After many decades of DST, some members of Congress are looking to change things once again by passing the Sunshine Protection Act. Proponents of the Sunshine Protection Act contend that keeping time consistent throughout the year would be better for peoples’ circadian rhythms, that DST saves energy, and that DST stimulates the economy. The argument about saving fuel is an old one, and the other two given reasons have been floating around for a while. Supposedly, DST will stimulate the economy by creating longer evenings, thus encouraging people to shop more, and also benefit the circadian rhythm with its consistency.

Opponents of the Sunshine Protection Act argue that permanent DST would cause an increase in traffic accidents, disrupt religious rituals, and worsen seasonal depression. The traffic accidents and depression would owe to dark mornings, which are gloomy and especially hazardous to schoolchildren. The disruption of religion is because many religions have rituals, such as times for prayer, that depend on sunlight. Kayla Lieberman, a Jewish high school student, explains, “Having permanent Daylight Saving Time will be a big inconvenience to Jews who want to pray in the morning, as tefillin are only allowed to be put on after dawn. People who usually pray early in the morning before going to work will be unable to do so if the sun rises in mid morning.”

Whether or not it is passed, the Sunshine Protection Act wouldn’t go into effect until 2023. So on Sunday, November 6th, 2022 you were able to reset your clock and steal an hour of sunlight in the morning. Of course, you’ll be losing an hour at night, but that can’t be helped. For now, just continue falling back and waiting for the sun to return.

You grew up learning to “spring forward, fall back” by manually resetting each clock in your apartment, and then you bought a smartphone to spring and fall for you. Now time jumping back and forth is as normal to you as the flowers blooming or the leaves turning red.

Tamar Padwa is a Chief Graphic Designer and Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Observatory’ yearbook. She is also a Staff Reporter for 'The Science Survey.'...