Our Language is Not Yet Settled: A Need to Rethink Style Guides of Today

Style guides help to standardize the written English language, a matter of great responsibility.

The English language is constantly evolving, and style guides need to evolve as well.

The legendary New Yorker writer E.B. White types away at his column, a regular occurrence to match his regular dissatisfaction with the published result. Tumultuous string-upon-string of words served his biggest headache, as his wracking brain sought to provide ease and concision to the readers of his worthwhile thoughts.

To cut this story short, he answered his woes with a personal rediscovery of an old tool: the style guide.

“It was a forty-three page summation of the case for cleanliness, accuracy, and brevity in the use of English,” White later wrote. Published initially in 1918, it laid out the hard-and-fast rules for how to navigate the turmoils of writing – outlining uniform standards for grammar, punctuation, and formatting – basically regulating, for all, its namesake, The Elements of Style.

The Elements of Style was a revolution in how America writes, and it has since paved the movement for consistency in all published pieces of academic writing, such as research reports and journalistic articles. Joined by a few successors, namely The Chicago Manual of Style and the Associated Press Stylebook, style guides of today are the vital force that help to standardize the written English language. And with those accolades comes an incredible responsibility, because a society divided by racial, sexual, and gender injustice is harmed by unregulated terminology on the discourse of oppression.

Simply stated: if the style guide can standardize language, it can standardize equity. This is the musing of a new movement, one spearheaded by the ambitious journalist, Nikole Hannah-Jones.

“We have allowed language to both soften and erase the condition and humanity of [enslaved] people,” Hannah-Jones asserts. “We have to stop letting the language hide the crime.”

The seminal work of Nikole Hannah-Jones culminates in the long-form journalism endeavor, “The 1619 Project.” She has orchestrated the ongoing collaborative as a way to illustrate the intrinsic effect that slavery has had on our United States’ history. And for this project, she has created a style guide.

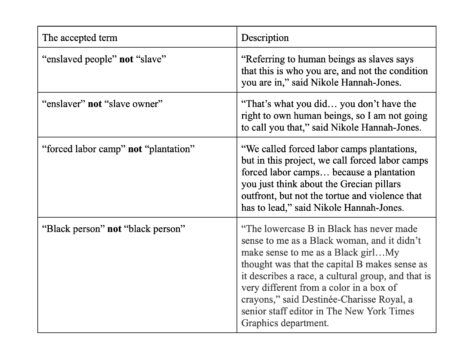

Her style guide has yet to be published, but Hannah-Jones has elaborated on a few major points. In particular, the use of the words “enslaved person” not “slave,” “enslaver” not “slave owner,” “forced labor camp” not “plantation,” and “Black person” not “black person.” As Hannah-Jones sets a new standard for racial terminology, she re-infuses the general topic of enslavement with the sense of equity it deserves.

The capitalization of the “B” in reference to the “Black” race has gained the most traction of the points made so far. Marc Lacey, national editor for The New York Times, said, “It seems like such a minor change, black versus Black. But for many people the capitalization of that one letter is the difference between a color and a culture.” Rachel E. Harding, professor of Ethnic Studies at The University of Colorado Denver, adds, “in the absence of the identifiable ethnicities slavery stole from those it subjugated, Black can be a preferred ethnic designation for some descendants.”

While many popular style guides have updated the capitalization of Black, most still neglect the other terminology updates that Nikole Hannah-Jones endorses. This is a problem for the publishing world, because it leaves a gray area where language is not settled. As a result, the purpose of style guides as enforcers of consistency in written English is entirely undermined.

The obstinance of such style guides is, however, not unfounded. Language is finicky, and unsettled language is even harder to pin down. The movement implied by Nikole Hannah-Jones, customizing once settled terms, permeates a legendary barrier in which fashionable discourse becomes institutionalized reality. Just as Hannah-Jones may advocate for the term “enslaved,” others will join her with their own terms. Opening a language to malleability opens floodgates that are hard to close.

Often cited as an example of amended language going too far is the term “Latinx.” The word was originally coined as a gender-neutral replacement for the words “Latino” or “Latina,” which are both gendered terms referring to a person residing in the U.S. that is of Latin American descent. Upon its founding in 2004 by Princeton University scholar Arlene Gamio, Latinx was used almost exclusively amongst academic circles to promote gender inclusivity. Later popularized by politicians and activists, the term has since accumulated more controversy than support.

“It takes all the Spanish out of the word,” said high school student Ava Lehmann ’24, who is of Dominican descent. Currently enrolled in Spanish II, she continues to study the basics of Spanish grammar, where it becomes increasingly clear to her that the term Latinx has no practical ability to coexist with the community it represents. The American-conceived term contains the “-ex” syllable that simply does not exist in the pronunciation of the Spanish language, and holds little precedence over the language that is entirely gendered to start with. “No one says amigx,” Lehmann also noted.

In fact, according to a 2019 study conducted by the cross-cultural research agency ThinkNow, the overwhelming majority of Hispanics prefer not to be called Latinx.

The term Latinx has clear ideological integrity, poised in its purpose of dismantling the binary terminology that represses Hispanic gender minorities. But in practice, the term stimulates more lingual detriment than radical reform.

Latinx exemplifies why style guides are stubborn with their amendments. If the innately performative term were to infiltrate the style guide, its elite purpose – to standardize the written English language – would be fundamentally blurred. Published writers will not want to use language that spurs offense and impedes their own achievement (cancels them, essentially), and the medium once entrusted to standardize American literature will collapse upon itself.

But just as a writer is harmed by language that is unduly progressive, they are also harmed by language that is behind the times. The common denominator between Hannah-Jones’ push for the use of the word “enslaved,” and various other intellectuals with their push for “Latinx,” both words strive for inclusivity and equity among minority groups, which is essential. While Latinx may not be an effective word at the end of the day, it does conjure necessary debate on the steps we must take to make language more gender-inclusive.

Style guides ultimately determine the words that make up our identities, so we as a society are responsible for settling such language with equity and respect. The greatest step we can take towards this form of linguistic justice is to be open to discussion — interrogate the terms you use to refer to yourself and others. Collective reflection, conversation, and analysis are key to working out the sociopolitical kinks in our unsettled language. English, after all, updates best through unity.

Style guides of today are the vital force that standardize the written English language. And with those accolades comes an incredible responsibility, because a society divided by racial, sexual, and gender injustice, is harmed by unregulated terminology on the discourse of oppression.

Yasmine Salha is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She is a proponent of accessible journalism, and loves to simplify complex and controversial...