After COVID-19, Can We Learn to Live With Germs Once Again?

How will we deal with the shift back to lifestyles that expose us to more bacteria?

Hand sanitizer sales spiked at the beginning of the Coronavirus pandemic in the Spring of 2020, driving prices up. On Amazon, certain sellers asked for over $300 for a single bottle of Purell.

The unmistakable label “Kills 99.99% of Illness Causing Germs” on Purell bottles — one of the top consumer hand sanitizers in the United States — instills confidence in individuals attempting to avoid invisible, lurking viruses and bacteria. Sales of hand sanitizer skyrocketed at the onset of the Coronavirus pandemic as it became an invaluable stopgap for hand-washing in our buzzing pre-pandemic lives. Today, these bottles are at the entrance of nearly every public space.

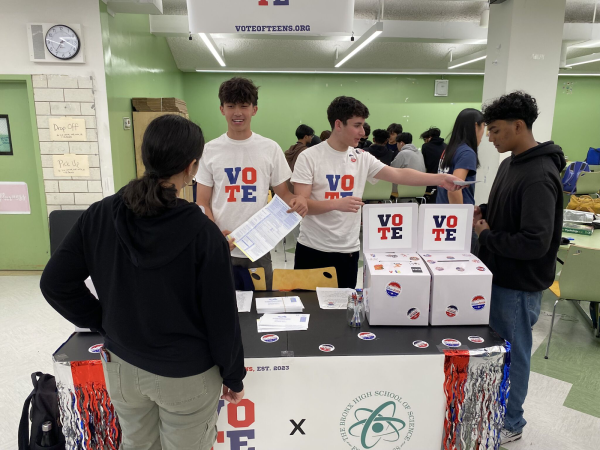

While many stores now require its use, hand sanitizer is only one measure on a list of new public health and safety precautions that people around the world have taken during the Coronavirus pandemic. Well-intentioned shifts to increase general standards of cleanliness have taken hold in order to encourage people to once again feel safe.

In airplanes, individuals wearing goggles and masks spray chemical mists, such as Matrix 3, to disinfect overhead bins and seats. In the New York City subway system, the MTA continues its historic cleaning efforts with over 75% of riders agreeing that the subway cars have never been more clean. In restaurants and gyms, both workers and customers display increased efforts to constantly clean used tables and equipment. Given that people were constantly instructed by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to clean personal spaces and avoid touching their eyes at the beginning of the pandemic in the Spring of 2020, sterilizing environments have always generated clean atmospheres and left people feeling safer.

Public comfort with clean areas is important, but Coronavirus researchers have found that COVID-19 infection by contact with contaminated surfaces is very low and the principal mode of infection is through respiratory exposure. Studies have reported that on porous surfaces, there is an inability to detect a viable virus within minutes to hours. On non-permeable surfaces, a viable virus can be detected for days to weeks.

Despite this information on the principal modes of transmission, the public continues with the implementation of its disinfection measures. Many of these measures may last indefinitely — and some public health experts are watching the disinfection wave with fear. The continued killing of germs on all surfaces may lead to us washing away the good microbes that our health relies on.

Microorganisms exist almost everywhere in the world. Our constant interaction with them fuels our immune system functions and trains various functions in the body. As reported by the New York Times, “There’s a wealth of evidence to suggest the microbiome has an influential role in our response to viral infections,” said Brent Williams, an assistant professor in the department of clinical pathology and cell biology at Columbia University.

There is also research on whether the loss of beneficial bacteria may cause individuals to become more vulnerable to infections. Scientists have shown that as populations get older worldwide, allergy manifestations in aged persons occur more often. The immune system can be prone to malfunctions that lead to allergies, autoimmune disorders, or other medical conditions when deprived of certain bacterial exposures. Fluctuations in the microbes that we are being exposed to due to COVID-19 cleaning measures may in turn impact how our bodies deal with bacteria in the future.

Over-cleaning various surfaces can also create more issues in the long run, concerning the development of Coronavirus variants along with other viruses. Research has indicated that the overuse of hand sanitizer can cause the development of antibacterial-resistant bacteria as a result. Whether this is unavoidable or can be prevented is unclear for all disinfectants. However, the increased sanitization that the pandemic has brought upon us has scientists questioning cleaning measures.

Our microbial communities are not always our enemies. As we implement hyper-cleanliness measures and with technology allowing us to work at home, the importance of living with germs without being exposed to viruses and risks remains. Indiscriminately washing away all bacteria in our path may put individuals at ease for a moment, but exposure to the good microbes is necessary for the long term.

“There’s a wealth of evidence to suggest the microbiome has an influential role in our response to viral infections,” said Brent Williams, an assistant professor in the department of clinical pathology and cell biology at Columbia University.

Karen Phua is a Copy Chief Editor for ‘The Science Survey.’ She enjoys journalistic writing for the connection that it provides with avid readers interested...