The Death Penalty Is Wrong. What Can President Biden Do About It?

An analysis of the moral and financial costs of capital punishment, the reasons why we have kept it, and the ways in which we can abolish it.

On January 20th, 2021, Joe Biden became the first sitting U.S. president to openly oppose the death penalty. Now, civil rights groups and members of Congress are pressuring him to fulfill his promises and end it.

The United States has a problem that it has been trying to solve for the past forty years.

No, it is not about wealth inequality, health care, or even climate change. The issue revolves around a central question. What is the best way to kill inmates on death row?

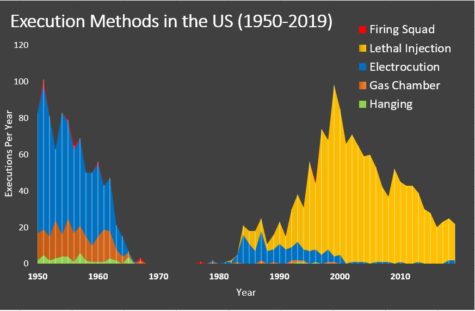

Electrocution, once a common method of execution, became unpopular in the 1980s due to several high profile malfunctions, and ever since, authorities have looked for a replacement. The main answer has been lethal injections, which have been used in about 88% of executions since 1976, but also have the highest botched execution rate. More than 7% of executions by lethal injection are botched, almost four times the botched rate for electrocutions.

The frequency of malfunctions with lethal injections and the fact that states are having difficulty obtaining the drugs they use for it have generated pressure for states to find alternatives. Some have moved back to older methods like the electric chair and firing squads. Others, like Nevada and Nebraska, have proposed opioid-assisted executions. One federal appeals judge even said the guillotine was “probably best” if it wasn’t “inconsistent with our national ethos.”

States can keep trying to come up with better ways to kill people, but they are avoiding a much simpler solution: eliminating the death penalty altogether.

The United States is currently sixth on a list of countries with the most executions behind China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Egypt, and remains the only country in the Americas to use the death penalty at all. More than 70% of the world has abolished the death penalty, with the United States being a particular outlier among democratic and allied nations in its preservation of the punishment.

There’s a reason why so many countries are eliminating the death penalty: it is immoral. First, the death penalty does not allow the justice system, which inevitably makes mistakes, to correct itself. Once someone is executed, it cannot be undone. “It’s too easy to be wrong to use a penalty that’s so irreversible,” said William Freedman ’21. In fact, a 2014 study found that at least 1 in 25 people who receive the death penalty are innocent.

On top of putting innocent people to death, the death penalty exemplifies a racist and unfair justice system. Black people make up 13% of the population, but constitute 42% of those on death row. A 2020 study found that defendants convicted of killing white victims were executed at a rate 17 times greater than those convicted of killing Black victims.

Even if the death penalty was morally justified, it is illogical. On average, it costs $620,932 per trial in federal death cases, which is eight times higher than a case where the death penalty is not sought. When including appeals, incarceration times, and the actual execution, a 2019 study found that across all fifty states, on average, a death row inmate costs $1.12 million more than a general population inmate. With 2,620 people currently on death row, that amounts to almost three billion dollars in additional expenses compared to if they had been sentenced to life in prison instead.

Supporters of the death penalty argue that it is simply retribution for heinous crimes. Yet, in addition to the fact that the state should not have the power to kill people, the death penalty does not help anyone.

“The thought of honoring our loved ones by killing another human being is not only counter-intuitive, but abhorrent,” writes Tanya Coke in an op-ed for USA Today. In the piece, she references her own sister’s murder in 2013 and argues against the death penalty in other cases as well. “[The death penalty is] a sad reminder of how our justice system typically offers punishment instead of healing for the survivors of violent crime.”

The billions of taxpayer dollars currently used for capital punishment would be much better spent on helping homicide victims and their families with trauma and grief counseling, financial support, and scholarships or even on measures to prevent these crimes from happening in the first place. Retribution should not be a justification in and of itself.

Another claim is that it deters crime. Firstly, there is no proof to support this claim. In fact, the FBI has found that states with the death penalty have the highest murder rates. Secondly, there were about 16,000 murders nationwide in 2018 and only twenty-five executions. It is improbable that the small chance of execution many years after committing a crime will affect the behavior of a murderer who would otherwise be willing to kill if their only punishment was life in prison.

So, if the vast majority of countries have eliminated the death penalty, why has the United States kept it?

David Garland, a Professor of Sociology at NYU and a leading sociologist on crime and punishment, writes that the answer to this question has to do with the structure of governance in the U.S. Governments in other countries appealed the death penalty through a single national reform, but the U.S. Congress cannot do the same because the Constitution gives legislative power over criminal law to the states. “Each of the 50 U.S. states (plus the federal government and the U.S. military) would have to repeal its own capital punishment law,” Garland writes.

There is only one American institution that can unilaterally abolish the death penalty — the Supreme Court — and it briefly did in 1972. Furman v. Georgia placed a moratorium on the death penalty in all states after ruling that it violated the constitutional guarantees of equal protection, due process, and the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishments. Following this decision, however, many states passed new legislation to reform procedures and establish safeguards against discrimination, and the court ruled in 1976 that the death penalty could be constitionally valid under the correct procedures. The moratorium was short-lived.

(Original graph by Yona Litwin)

Today, although Americans’ support for the death penalty has reached its lowest point since 1972, two recent pro-death penalty decisions make it unlikely that there will be a modern-day equivalent of Furman. Glossip v. Gross (2015) and Bucklew v. Precythe (2019) make it harder for inmates on death row to argue their executions violate the constitutional prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. Especially with a new 6-3 Republican majority, the chances of the Supreme Court abolishing the death penalty in the near future are close to none.

So, if change is unlikely to come through the Supreme Court or Congress alone, what can Biden do?

First, he can, and should, eliminate the federal death penalty. Although states are the most common practitioners of the death penalty, the federal government has it too in cases when states cannot or will not use it themselves. The federal death penalty was brought to public attention in 2020 when President Trump resumed federal executions following a 17-year suspension, overseeing the executions of 13 death row inmates.

Biden can immediately enact three executive orders to stop federal executions during his presidency. These include simply telling the Justice Department not to schedule any executions, prohibiting prosecutors from seeking new death sentences, and commuting the death sentences of the 49 inmates currently on federal death row. However, for a federal death penalty ban to last past his presidency, he needs to get Congress involved. The Federal Death Penalty Prohibition Act, which was supported by 37 members of Congress in a letter to Biden, would do just that. A complication is that Biden would have to persuade Republicans to get it passed.

Stopping the federal death penalty, although important, is far from enough. The federal death penalty has accounted for only 16 of the 1,532 executions since 1976. As part of his campaign, Biden pledged to “incentivize states to follow the federal government’s example,” but did not specify how he would do this. One approach could be to slow down executions by withholding federal grants until states meet certain requirements like giving prisoners DNA tests that may help prove their innocence, but it unclear if the Biden Administration would support aggressive measures like this.

Ultimately, national legislation needs to be combined with action from local and state governments to completely put an end to executions. The good news is that states are moving in that direction. More than two-thirds of the country (34 states) have either abolished the death penalty (22 states, with Virginia becoming the 23rd later this year) or not had an execution in the last ten years (12 more states). In addition, both executions and death sentences are on the decline, as the U.S. reached its sixth consecutive year with 50 or less death sentences and 30 or less executions.

The death penalty may be slowly dying, but until it is eliminated for good, it will continue to put innocent people to death, disproportionately target Black people, and throw away billions of taxpayer dollars. Entering office, President Joe Biden is facing a variety of crises that must take priority, but doing his part to end capital punishment cannot fall through the cracks.

“The thought of honoring our loved ones by killing another human being is not only counter-intuitive, but abhorrent,” writes Tanya Coke.

Yona Litwin is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey.' He enjoys the fact that journalistic writing is driven by a variety of voices, and that a single...