We Cannot Let the Coronavirus Pandemic Derail Voting

As the Coronavirus pandemic forces election procedures to change, President Trump and his enablers are fighting to disenfranchise voters.

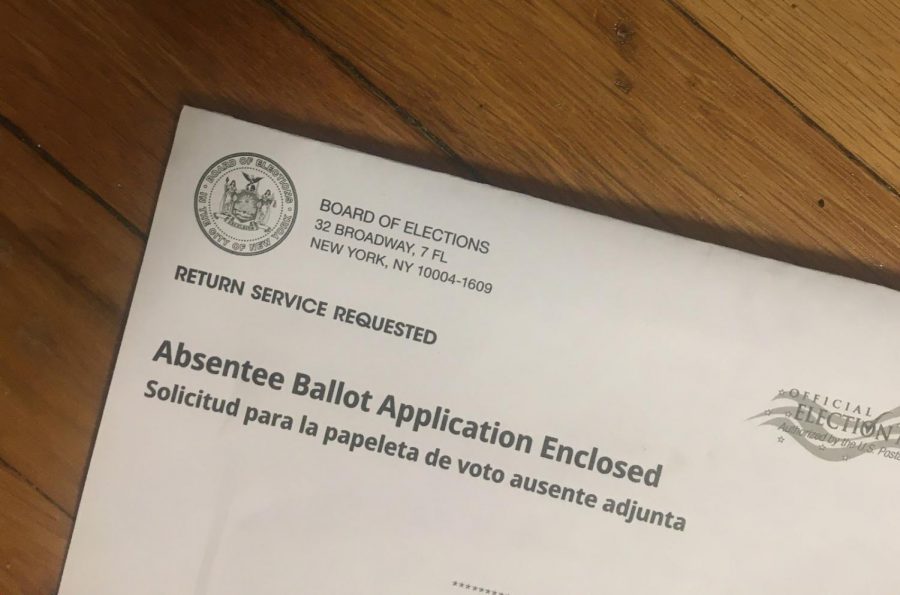

New York State sent a request for an absentee ballot in the June 23, 2020 primary elections to every registered voter. It is one of many states that have looked to expanding voting-by-mail in the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic.

On April 7th, 2020, in the midst of a statewide shutdown over the coronavirus, Wisconsin held its presidential primary. Just a few days prior, Democratic Governor Tony Evers had attempted to postpone the election, but had been blocked by the state’s conservative Supreme Court. Many Republicans, including President Donald Trump, urged Wisconsin residents to get out and vote, despite the looming threat of the COVID-19. The Republican speaker of the state assembly, Robin Vos, held a press conference where he claimed it was “completely safe to go out.” Ironically, he was dressed in head-to-toe personal protective equipment, while promising voters they should not worry about heading to the polls.

The question of how to conduct elections in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic reaches far beyond Wisconsin. Even as states begin to open up, experts continue to warn that millions of voters heading to busy polling places on November 3, 2020 could be a recipe for a disaster. In Wisconsin’s primary, a lack of volunteer poll workers had disastrous effects on the accessibility of polling stations across the state. In Wisconsin’s capital and largest city, Milwaukee, there were only 5 polling stations open, when there are usually 180. The result: hours of waiting on line to vote— and thus, hours of possible exposure to COVID-19.

The lessons from Wisconsin’s primary experiment have inspired lawmakers on both sides of the aisle to call for the expansion of mail-in voting in their primaries and even in November. Five states already conduct their elections by mail, sending every registered voter a ballot without requiring them to request one first. Other states, including Wisconsin, allow residents to vote by mail upon request. But 15 states, including key swing states like Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, require excuses for voting by mail — and these states may not yet consider “fear of coronavirus” as a valid excuse.

Thankfully, many states have already passed new laws to expand the practice of voting-by-mail. Georgia, Michigan, and Nevada recently announced they will mail ballot requests to all registered voters. But the efforts of these states to expand voting-by-mail has been hampered, like so many efforts to mitigate the harms of this pandemic, by President Donald Trump. Trump has frequently attacked the use of mail ballots, claiming that it leads to widespread voter fraud. On May 13, 2020, he told a room full of reporters, “So the problem with the mail-in ballots: it’s subject to tremendous corruption. Tremendous corruption, cheating. And so I’m against it.” His railing against mail-in ballots has prompted him to criticize Republicans and Democrats alike who have sought to expand it. When Michigan’s Secretary of State announced the state’s support for voting-by-mail, he called her “rogue,” and threatened to withhold funding from the state as a punishment (which is not allowed).

Trump’s rationale for opposing voting-by-mail is that it encourages voter fraud, since he claims that ballots can be filled out by someone else, tampered with, or even destroyed. But he has not provided any evidence of this claim— instead, he relies on fake hypotheticals about ballots being purposefully compromised to change an election’s results.

The evidence tells a very different story. When examining vote-by-mail fraud (like someone impersonating someone else or destroying ballots), the problem is virtually non-existent. Richard Hasen, a Professor of Political Science at the University of California at Irvine School of Law, found that there were just 491 legitimate cases of absentee-ballot fraud in every election from 2000 to 2012 — 491 cases out of billions of votes cast. Even in these unlikely instances of voter fraud, they are rarely the result of fully-fledged conspiracies, and they have not ever had the significance to change the results of an election.

The main problem with mail-in ballots is not fraud, but administrative errors. Mail-in ballots are verified by election officials, who check that all paperwork was filled out correctly, on time, and that the voter’s signature on the ballot matches the signature in the state database. If any one of those things is not true, the ballot can be rejected. The rejection rate for mail-in-ballots is higher than you might think: in the 2018 midterm elections in Florida, for example, 1.2 percent of all votes-by-mail were rejected, resulting in over 32,000 wasted votes. Voters whose votes are wasted are disproportionately likely to be younger, first-time voters, or racial or ethnic minorities.

The rejection of mail-in-ballots is usually the result of overcomplicated laws, coupled with election officials providing voters little guidance on how to correctly vote by mail. A 2018 study by Columbia University Professor of Political Science Lorraine Minnite found that most of the time, problems with mail-in voting is the result of administrative or voter errors, and accusations of fraud are mostly last-ditch attempts by losing candidates who desperately fabricate such claims. Minnite writes that, “poor record management on the part of elections officials” is the problem behind voter fraud cases, even as “voters got the blame.”

There are easy ways to expand voting-by-mail without incurring the risk of fraud or throwing out thousands of rejected ballots. The application process and design of the ballots must be simplified in order to prevent easy mistakes. Politicians and officials must clarify and disseminate more information on voting-by-mail, so that voters know that they have the option. Mail-in ballot requests should be mailed to every registered voter in the state, to ensure that people who actually want to vote will request one. There should be a grace period for voters whose ballots were rejected to fix the problems with their ballots and to ensure that their vote is counted. And finally, states should limit the use of ballot harvesting, which allows citizens to collect people’s ballots and thus incurs the (extremely minor) risk that someone could destroy boxes of votes.

But President Trump’s real reason for opposing mail-in ballots is out of fear of losing in November 2020, not out of concern about fraud. Trump and other Republicans have frequently expressed concern that expanding voting-by-mail will increase the number of Democratic voters, with Trump saying in an interview on Fox News that expanding absentee ballots means “you’d never have a Republican elected again.”

The problem with Trump’s claim about voting-by-mail disadvantaging Republicans is that, like his claim about voter fraud, it is contradicted by the weight of empirical research about mail-in voting. An April 2020 study by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research concluded that mail-in ballots actually increase voter turnout for each party equally. Overall, the study found that having an option to vote by mail can boost turnout by more than 2%.

Importantly, President Trump does not actually have any jurisdiction over voting by mail; election procedures are determined at the state level, not the federal one. But his rhetoric still matters, since it has riled up GOP opposition to mail-in ballots across the country.

In a 2020 report by The Washington Post, Marc Elias, a Democratic lawyer, explained that Republicans have been looking to weaken voting-by-mail for years, and Trump’s opposition gave them the opportunity to make this pipe dream a legitimate reality. “Because Donald Trump has normalized all of these crackpot theories about voter fraud, [opponents of voting-by-mail] have all now joined forces under the banner of the legitimate Republican establishment,” Elias said. After Minnesota’s secretary of state announced the state’s intention to mail a ballot to every registered voter in November, the state’s Republican Party chairwoman claimed that “the apocalypse has arrived.” And just last week, the Republican National Convention filed a lawsuit against California to block the Democrat governor’s attempts to send voters mail-in ballots.

So while the President does not control how voting occurs, his staunch attacks have spurred on the efforts of Republicans to block voting-by-mail in November 2020. The president’s fear that he will be defeated in November is not a legitimate reason to oppose expanding voting-by-mail, and his false claims about it are a blatant attempt at voter suppression. Accusations of voter fraud have historically been used to disenfranchise marginalized groups. After the Civil War, for example, Southern Democrats justified harsh new voting restrictions by claiming they prevented fraud, when in reality all they prevented was millions of black people from being able to vote. Trump’s railing against mail-in voting today is just another form of disenfranchisement, by forcing Americans to choose between their right to vote and their health. That is not a fair choice to make, and it is not how a democracy should function.

This does not mean, though, that mail-in ballots should be the only available form of voting in November 2020; physical polling places are crucial parts of our elections, and they must remain open. But the coronavirus pandemic will not disappear by November, and Americans should not feel like they must prioritize their constitutional right to vote over their own safety. This country has adapted to unique, unprecedented circumstances before; voting-by-mail was established during the Civil War, to allow Union soldiers to vote while serving. We can improve our democracy to meet the demands and challenges posed by this crisis, too.

So while the President may not control how voting occurs, his staunch attacks have spurred on the efforts of Republicans to block voting-by-mail in November 2020.

Kate Reynolds is currently an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey,’ and was a Groups Editor for 'The Observatory' yearbook during the 2019-2020...