The Romantic era, a time of towering figures and revolutionary ideas, often celebrated the artist as hero, and the composer as genius. Yet, in this storied period, the name Louise Farrenc remains curiously discounted — a composer who crafted meticulously balanced symphonies and chamber works while subverting the constraints placed upon women in 19th-century music. Farrenc’s life, marked by brilliance and defiance, unfurls as a testament to the quiet rebellion of a woman unwilling to be confined by social expectations. Her journey from the rarefied halls of the Louvre to the venerated Paris Conservatoire reveals an artist deeply rooted in the classical tradition but propelled by a vision that was distinctly her own.

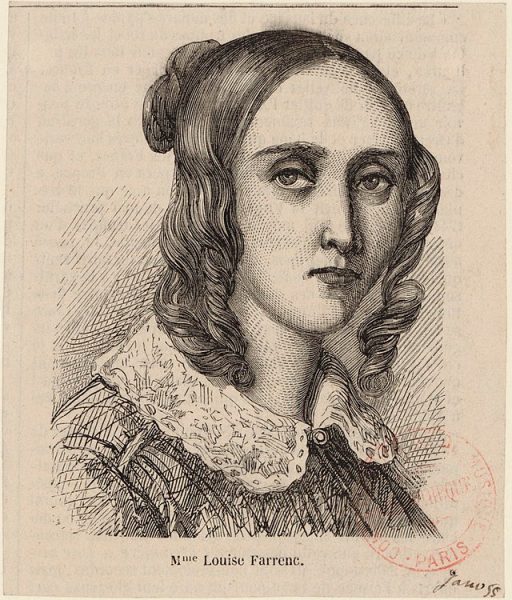

Louise Farrenc was born Jeanne-Louise Dumont on May 31st, 1804, in Paris, into a family deeply rooted in the visual arts. Her father, Jacques-Edme Dumont, was a court sculptor for Louis XVI, and her mother came from the prestigious Coypel family of painters. Raised within the artistic precincts of the Sorbonne Université, she lived in a world infused with creative expression, where the visual and performing arts converged to shape her earliest inspirations. In such an environment, Farrenc found herself drawn to music from an early age, exhibiting a natural talent that would lead her down a path only a few women of her time would have the freedom to pursue.

Her formative years were marked by rigorous training with some of the leading performers of her day. Initially, she studied piano under Ignaz Moscheles, a virtuoso known for his exacting technique and expressive phrasing, and later with Johann Nepomuk Hummel, whose polished style and musical complexity would leave a lasting imprint on her own compositions.

Seeking to deepen her knowledge, she began formal studies in composition with Anton Reicha, a visionary teacher and theorist who influenced composers as varied as Berlioz, Liszt, and Franck. Reicha’s influence can be seen in Farrenc’s later works, which reveal a profound understanding of counterpoint, harmonic invention, and thematic development — qualities that were relatively rare among French composers.

At the age of 17, Louise married Aristide Farrenc, a flutist and music publisher who would become a vital partner in both her personal and professional life. The couple shared an egalitarian partnership-an anomaly in 19th-century France, where even talented women were often sidelined by the careers of their husbands. Aristide, however, fully recognized and supported Louise’s talent, and together they became influential figures in Parisian music.

Their most significant collective endeavor was the Trésor des Pianistes, a multi-volume anthology that preserved the most important works in the piano repertoire from previous centuries. The project served as both a teaching tool and a historical reference, aligning with Farrenc’s strong commitment to music education and scholarship. This work not only elevated her reputation but also solidified her place in music history as a scholar and educator who was deeply dedicated to preserving the classical tradition for future generations.

In 1842, Farrenc achieved what few women in her time could: she was appointed Professor of Piano at the Paris Conservatoire, a position she would hold for the next 30 years. Her appointment was revolutionary, given the institution’s overwhelmingly male faculty and its attitudes toward female musicians. Throughout her tenure, Farrenc trained some of the era’s most promising pianists and built a reputation as a teacher who demanded the highest standards of technical mastery and interpretive depth.

However, her position highlighted a glaring inequity:her male colleagues earned higher salaries despite holding the same title and responsibilities. In a bold move that demonstrated her commitment to gender equality, Farrenc demanded — and eventually secured — equal pay in 1850, setting a precedent that was as groundbreaking as her music. Her victory was a landmark moment, challenging the pervasive sexism of her era and reflecting her determination to be recognized as an equal in the field she had devoted her life to.

Perhaps Farrenc’s most courageous compositional achievements lie in her three symphonies. In an age when French music was dominated by opera, particularly in the Romantic era’s sentimental and florid style, Farrenc sought inspiration from German classicism, drawing on the influences of Beethoven, Mozart, and Haydn. Her symphonies are a testament to her technical expertise and deep understanding of the form, qualities that allowed her to stand alongside her male contemporaries, though they did not grant her the same recognition.

Her Symphony No. 1 in C minor is an audacious work that showcases Farrenc’s grasp of form and her capacity for thematic development. In the opening Allegro, she establishes a turbulent C minor theme, weaving it through complex counterpoint and dynamic orchestration that recalls Beethoven’s early symphonies.

The Andante second movement shifts into a more lyrical mode, providing a pastoral contrast to the first movement’s intensity. Her ability to sustain tension and resolve it harmonically displays a sophisticated handling of orchestration and thematic unity. Although this symphony was modestly received, it demonstrated Farrenc’s potential as a symphonist in an era when such large-scale compositions were rare among women.

In her second symphony, Farrenc’s orchestration becomes more assured, with a broader harmonic palette and more pronounced Romantic sensibility. The symphony’s outer movements are marked by exuberant rhythmic vitality and tightly woven themes that evoke the lightness and elegance of Classical structures, while also pushing toward the emotional expressiveness of Romanticism.

The Adagio, in particular, reveals Farrenc’s capacity for lyrical writing, unfolding a serene, almost contemplative theme that is supported by rich, chromatic harmonies. Her use of the woodwinds to add color and depth to the texture reflects her growing confidence in orchestration.

Her final symphonic work, Symphony No. 3 in G minor, is widely regarded as her symphonic masterpiece. This symphony opens with an Allegro that plunges immediately into a dramatic G minor motif, creating a sense of urgency that propels the listener through intricate harmonic progressions. The movement’s structure is tight, yet Farrenc manages to infuse it with an intense emotional quality that echoes Schumann’s symphonic style.

The slow second movement, an Adagio, is characterized by lush harmonies and a plaintive theme that rises and falls with a deeply Romantic expressiveness. This movement alone cements Farrenc’s status as a symphonic composer with a distinct voice, one capable of exploring complex human emotions through orchestration.

In the final movement, Farrenc combines elements of folk dance rhythms with contrapuntal textures, creating a rousing conclusion that balances the symphony’s emotional weight with a sense of resolve and optimism. Laurence Equilbey, a modern conductor and advocate for Farrenc’s music, has described her third symphony as a “masterpiece” and as a “vital addition to the Romantic symphonic canon.”

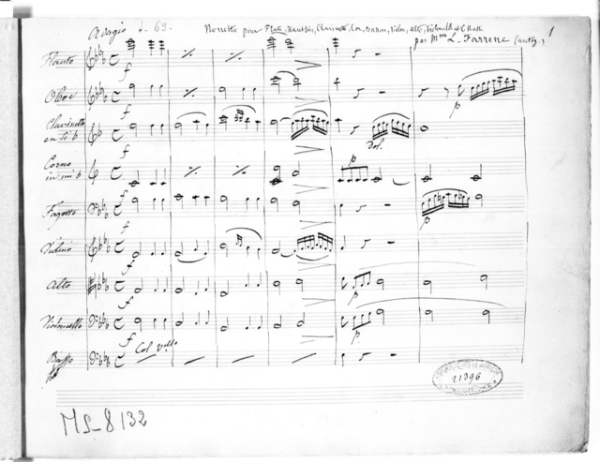

While her symphonies are impressive, Farrenc’s chamber music stands as perhaps the clearest expression of her artistic vision. Her Nonet in E-flat major is her crowning achievement, featuring an ensemble of strings and winds that showcases her skill in handling diverse textures and instrumental voices.

Composed for a lineup of some of the greatest musicians of her day, including violinist Joseph Joachim, the Nonet received immediate acclaim and positioned Farrenc as a prominent figure in chamber music. This piece is celebrated for its transparency of texture and the equal distribution of thematic material among the instruments, allowing each voice to participate in a rich, contrapuntal conversation. In the Nonet, Farrenc’s mastery of both Classical and Romantic idioms shines through, blending the structural clarity of Mozart with the expressive freedom of the Romantic era.

Farrenc’s piano quintets further illustrate her mastery of chamber forms, where the piano and strings engage in a fluid, dynamic dialogue. The A minor quintet opens with a hauntingly somber theme, weaving a sense of melancholy that is tempered by lyrical passages in the strings.

In contrast, the E major quintet brims with a brighter, almost pastoral quality, revealing Farrenc’s capacity to balance emotional intensity with classical restraint. Throughout these works, her keen understanding of instrumental interplay is evident, allowing her to create chamber music that is at once intimate and symphonic in scope.

Despite her achievements, Farrenc’s career was continually hindered by the gender biases of her era. The 19th-century Parisian musical establishment favored men for roles as symphonists and chamber composers, relegating women to domestic genres or limiting them to the “salon music” tradition, which critics often deemed secondary.

While male contemporaries like Berlioz and Chopin were celebrated, Farrenc faced skepticism and marginalization, with her works rarely reaching the same audiences or critical acclaim. Her compositions were regarded as anomalies, praised for their craftsmanship but not seen as part of the larger Romantic canon — a reflection of the limitations society imposed on female composers.

Due to the cultural barriers she encountered, her achievements were largely overshadowed by her male peers. Only in recent decades has her work been revived and celebrated, giving audiences a chance to appreciate the breadth and depth of her contributions to music history.

Today, Farrenc’s compositions are being increasingly performed and recorded, gaining recognition for their originality, structural sophistication, and emotional depth. Her music, now celebrated for its craftsmanship and artistry, embodies her belief in the power of the classical tradition to communicate, transform, and endure. As audiences continue to rediscover her works, Farrenc’s legacy grows stronger, redefining her place in music history and expanding our understanding of the Romantic era.

Farrenc’s life, marked by brilliance and defiance, unfurls as a testament to the quiet rebellion of a woman unwilling to be confined by social expectations.