The holiday season brings certain things to mind: snow-dusted treetops and the smell of balsam and fir, warm hot chocolate with marshmallows, and colorful ornaments adorning trees. The traditions that we carry on in this season, whether connected to religion or not, make this time of year special.

For many, The Nutcracker is a critical part of this holiday spirit; hundreds of thousands of people around the world flock to see the classic ballet every year. The performance, which has only grown in popularity since its first unveiling in St. Petersburg in 1892, is a winter classic and one of the most commercially successful and well-known ballets of all time.

The Nutcracker can be unraveled into a series of complex layers: the story it tells, its history, choreography, and Tchaikovsky’s musical composition which narrates the show. All of these elements combine to form The Nutcracker.

The Nutcracker’s influence can be seen worldwide; annual performances are hosted in several major cities in the United States as well as in various locations around the world. The performances in London and Paris, for example, are often very successful and attract plenty of visitors eager to see the ballet. And in New York City, The Nutcracker is something of a cultural touchstone. It attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors every year and is extremely lucrative, to the extent that ticket sales for the event account for a large portion of the New York City Ballet’s budget each year.

The story told by the ballet differs slightly in each production, but the basic premise centers around the gift of a wooden nutcracker. In the New York City Ballet’s production of George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker, a young girl named Marie is gifted the nutcracker by her godfather Herr Drosselmeier during the family’s annual Christmas party. What happens next is an incredible journey through a fantastical world, a story told through a brilliant composition and excellent choreography. A full synopsis of the ballet can be found here.

The origins of The Nutcracker are complicated; its most direct basis is Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Nutcracker, which itself is a more kid-friendly version of E.T.A Hoffmann’s original story, The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. The latter explores darker themes, with a main point of contention in the story being the struggle between Marie’s strict, rule-abiding family and her fantastical journeys at night through the magical kingdom of the nutcracker. While the novella ends happily for Marie and the nutcracker, the reader is left wondering whether there truly was a whimsical world she would escape to nightly or if it was just a figment of her imagination.

Dumas’s version of the story lightens it a bit and makes it more palatable for a kid-friendly Christmas performance; that alteration of the original story is usually the one used in ballet performances of The Nutcracker.

The composition of The Nutcracker is also extraordinarily good. Tchaikovsky’s original score is still deployed in performances of the ballet, to widespread acclaim. A notable aspect of the ballet’s score is its use of the celesta, an instrument similar to a piano. It produces the delicate notes heard in “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy,” one of the most well-known melodies from The Nutcracker.

The Nutcracker was Tchaikovsky’s final composition, completed just a year before his death. The ballet premiered in Russia in December of 1892 at the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg. Somewhat surprisingly, considering how well-loved the ballet is now, that first performance was widely regarded as a failure. Critics and audiences disliked the ballet, and even Tchaikovsky remarked that it was “rather boring” in a letter to a friend.

However, the ballet continued to be performed in other countries and eventually went on to become one of the most commercially successful ballet performances in history. Its legacy continues on today, with thousands of people going to see The Nutcracker performance in New York City alone. Due to the Christmas party setting as well as the tradition of performing the ballet during the winter season, The Nutcracker has also become associated with Christmas and the holiday season as a whole.

George Balanchine is credited with popularizing the classic ballet and giving it a contemporary spin; as co-founder and long-term artistic director of the New York City Ballet, he revolutionized The Nutcracker and introduced it to a new middle-class audience in New York City. The first performance of The Nutcracker by New York City Ballet was on February 2nd, 1954 — over seventy years ago. Balanchine is one of the reasons why the ballet remains a cultural icon in the city decades later.

As a child studying at the Imperial School of Ballet in St. Petersburg, Russia, Balanchine held many roles in the production of The Nutcracker growing up. He had fond memories of these performances and felt that The Nutcracker was something inexplicably connected to Christmas; his decision to have children studying at the School of American Ballet perform in The Nutcracker carries on this legacy. According to the production’s website, over 125 children from the school appear in two alternating casts.

Balanchine made The Nutcracker what it is today: a performance with stunning choreography and incredible decor elements that draw the audience into the action, most notably a $25,000 Christmas tree that he advocated for. The tree grows to a height of 41 feet during the performance, and its transformation is part of what makes the performance so magical. Watching it, I shared Marie’s wonder as the tree stretched taller and taller, until the top of it was no longer visible from the audience. It marks a significant point in the ballet, demonstrating the departure from reality to fantasy.

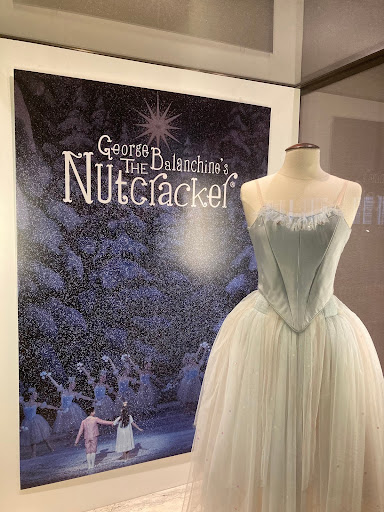

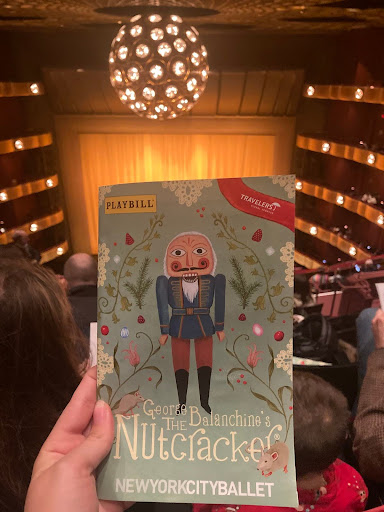

I had the opportunity to see the New York City Ballet’s production of George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker with the Bronx Science Arts & Culture Initiative on December 15th, 2024.

I had a clear view of the stage despite how high up my seat was. Due to the theater’s policy against photography during performances, I wasn’t able to take any photos during the ballet. However, I took photos of the theater and the playbill I received there. The theater — David H. Koch Theater, at Lincoln Center — was beautiful, with a huge sparkling chandelier dangling above the orchestra seats.

The performance itself was incredible. I had never seen The Nutcracker growing up, so even though I always wanted to see one and imagined how amazing it would be, I didn’t fully comprehend the scale of it until I was in the theater watching it myself.

The ballet starts simply — Marie and her younger brother, Fritz, are watching the preparations for their family’s annual Christmas party. The Christmas party is a joyful gathering of friends and family; the children embrace each other happily and dance alongside their parents. It’s a cute, if not particularly interesting, scene.

The real action begins when Herr Drosselmeier, Marie’s godfather, shows up. With his stark black cloak and electrifying presence, he commands the room and draws everyone’s attention to him. He comes bearing gifts, one of which is the titular nutcracker.

When the party ends and night falls, the fun begins: Marie sneaks out of her room and, in horror, observes the life-size mice scurrying about the room. Nutcracker soldiers emerge from the wings ready to fight, with the nutcracker her godfather gave her taking the lead. The mouse king and the nutcracker proceed to spar, their swords making satisfying sounds that cut through the rich melody of the orchestra.

The nutcracker defeats the mouse king with Marie’s assistance, and the mice and nutcracker soldiers vacate the stage. Marie is left alone, and she goes back to bed. The bed moves around the perimeter of the stage as snow-topped trees descend and snow softly falls from above, giving the appearance of a total transformation of setting. When Marie awakens, she is no longer in her home; she is in the Land of Sweets.

The nutcracker becomes the prince in a swift transformation, and he and Marie enjoy the rest of the ballet from the background. The second act is much less plot-forward than the first act, consisting almost entirely of nonstop dancing by the various dancers representing different sweets and beverages.

Personally, I enjoyed the Snowflake and Candy Cane dances most; the way the Snowflake dancers twirled and elegantly moved around the stage emulated exactly what snowflakes look like when they fall to the ground. Moreover, I thought that the Candy Cane dancers, energetically jumping through hoops and dancing around the stage, represented the jolt of minty sweetness one feels when eating a candy cane. Details such as the choreography and costumes elevated the performance, making it incredibly enjoyable and entertaining.

All in all, it was an amazing ballet performance. I went into the theater with technical knowledge of the performance — the basic plot, the ballet’s origin and history, and its composition — and exited it with a greater understanding of what makes The Nutcracker a performance people return to see year after year.

You can see the New York City Ballet’s production of George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker through January 4th, 2025.