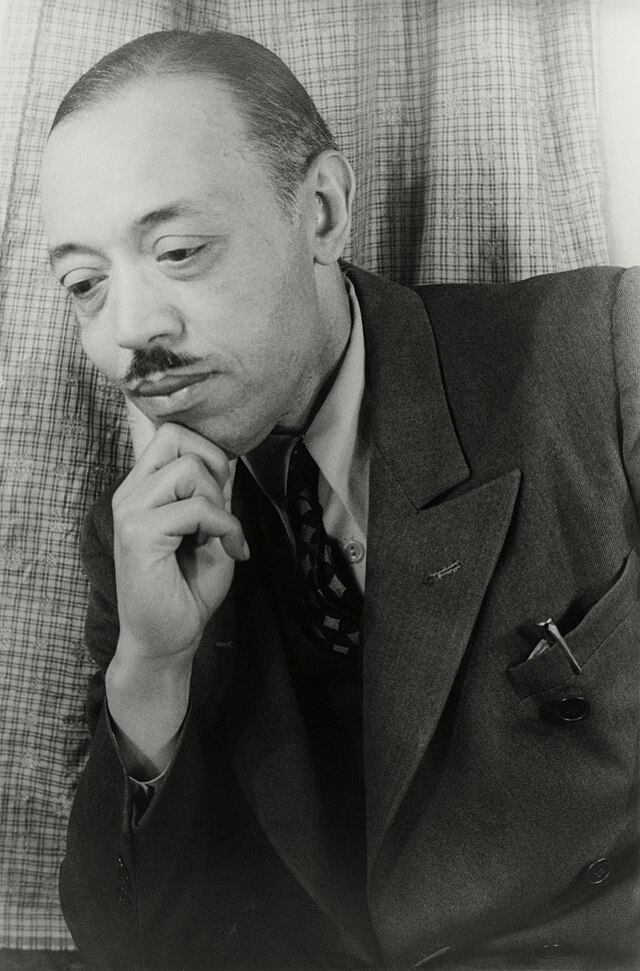

When the pantheon of great American composers is discussed, names like George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein often dominate the conversation. Yet one towering figure, whose symphonies and operas have profoundly shaped the landscape of American music, is frequently overlooked: William Grant Still.

Known as the “Dean of African-American Classical Composers,” Still’s journey from a small town in Mississippi to the grand stages of America’s foremost concert halls is a story of relentless determination, groundbreaking achievements, and a legacy that continues to inspire. His rich tapestry of compositions, infused with the rhythms and melodies of his cultural heritage, stands as a testament to his genius and his unwavering commitment to elevate African-American music to the heights of classical art.

Still’s parents, both educators and musicians, instilled in him a deep appreciation for music from an early age. Tragically, Still’s father passed away when he was just a few months old, prompting his mother to move to Little Rock, Arkansas, where she continued to teach English at a high school. It was here that Still’s musical journey began, nurtured by violin lessons and the operatic recordings that his stepfather introduced to him.

Still’s formal education took him to Wilberforce University, where he initially pursued a Bachelor of Science degree. However, his true passion lay in music. He spent much of his time conducting the university band, mastering various instruments, and making his first forays into composition and orchestration. Recognizing his burgeoning talent, the Oberlin Conservatory of Music extended a scholarship to Still, enabling him to further hone his skills.

Post-college, Still ventured into the realm of commercial music, where he played in orchestras and worked as an arranger. His proficiency with the violin, cello, and oboe caught the attention of notable figures such as W.C. Handy, Don Voorhees, Sophie Tucker, Paul Whiteman, Willard Robison, and Artie Shaw. During this period, he also conducted the Deep River Hour on CBS and WOR, showcasing his versatility and broadening his influence.

A pivotal moment in Still’s career came while he was in Boston, playing the oboe for the orchestra of the musical Shuffle Along. He applied to study at the New England Conservatory under George Chadwick, securing yet another scholarship. This period of study, alongside the tutelage of the avant-garde composer Edgard Varèse, enriched his compositional voice.

The 1920s saw Still emerge as a serious composer in New York, developing a significant friendship with Dr. Howard Hanson of Rochester. He was the recipient of extended Guggenheim and Rosenwald Fellowships, and received commissions from prestigious institutions such as the Columbia Broadcasting System, the New York World’s Fair, the League of Composers, and the Cleveland Orchestra. His Festive Overture won the Jubilee Prize from the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra in 1944, and in 1953, his work To You, America! earned him the Freedoms Foundation Award.

Throughout his life, Still’s contributions were recognized with numerous honorary degrees from institutions such as Wilberforce University, Howard University, Oberlin College, Bates College, the University of Arkansas, Pepperdine University, the New England Conservatory of Music, the Peabody Conservatory, and the University of Southern California.

His accolades included the Harmon Award, trophies from the Musicians Union A.F. of M., the League of Allied Arts, the National Association of Negro Musicians, and citations from the Los Angeles City Council and Board of Supervisors.

In 1939, Still married Verna Arvey, a journalist and concert pianist who became his primary collaborator. Their partnership extended beyond the personal to the professional realm, with Arvey playing a crucial role in the creation and promotion of Still’s works. They remained together until Still’s passing on December 3rd, 1978, due to heart failure.

William Grant Still’s career was marked by numerous groundbreaking achievements. He was the first African-American composer to have a symphony performed by a major orchestra, the first to conduct a major symphony orchestra in the United States, and the first to have an opera produced by a major company. His opera, Troubled Island, premiered at the City Center of Music and Drama in New York City in 1949, and was also the first to be televised nationally.

Still’s oeuvre includes over 150 compositions, spanning operas, ballets, symphonies, chamber works, and arrangements of folk themes, particularly African-American spirituals. His ability to infuse classical music with an authentic American spirit set him apart as a pioneer. His compositions garnered interest from the most esteemed conductors of his time, solidifying his place in the pantheon of great American composers.

One of his most celebrated works is the Afro-American Symphony, which holds a special place in the history of American music. The Afro-American Symphony, composed in 1930 and first performed in 1931, is perhaps Still’s most renowned composition. It is notable not only for its musical innovation but also for its historical significance as the first symphony composed by an African-American to be performed by a major orchestra. This work is a vibrant fusion of traditional symphonic form with blues and jazz elements, reflecting Still’s desire to elevate these African-American musical idioms to the realm of high art.

Still’s approach to composition was deeply rooted in his personal experiences and cultural heritage. He often drew inspiration from the rich tapestry of African-American music, infusing his compositions with melodies and rhythms that echoed the spirituals, blues, and jazz he grew up with. In an interview with Eileen Southern, Still emphasized the importance of inspiration in his creative process: “For me, music is beauty. Today, I feel there’s too much emphasis on experimentation for the sake of experimentation only. There’s too much contrived music — music written without inspiration. And inspiration is the spiritual force that touches the heart.”

His commitment to expressing the African-American experience is also evident in his opera Troubled Island, which premiered in 1949. This opera, with a libretto by Langston Hughes and Verna Arvey, is set in Haiti and addresses themes of revolution and liberation. The work was significant not only for its subject matter but also for being the first opera by an African-American composer to be produced by a major American opera company. Still’s collaboration with Hughes and Arvey on this project was a testament to his ability to merge powerful storytelling with profound musical expression.

Another significant work is Darker America, a tone poem that reflects the struggles and aspirations of African-Americans. This piece was performed by the International Composers’ Guild in 1926 and is characterized by its use of blues motifs and a structure that moves from a somber, introspective opening to a more hopeful and triumphant conclusion. Still described this work as an expression of the African-American experience, capturing both the pain and the resilience of his people.

Among Still’s notable compositions for solo piano is Three Visions, a suite that explores spiritual themes through a deeply personal lens. The second movement of this suite, ‘Summerland,’ has become particularly famous for its serene beauty and meditative quality.

‘Summerland’ is often performed as a standalone piece and is beloved for its tranquil and reflective character, which suggests a vision of an ideal afterlife. This work exemplifies Still’s ability to convey profound emotional and spiritual depth through music, offering listeners a glimpse into a peaceful and hopeful realm.

Throughout his career, Still’s compositions were marked by a deep respect for traditional musical forms coupled with an innovative use of African-American musical elements. His ability to navigate and merge these two worlds made his music unique. As he once explained, “I wanted to elevate the blues to a dignified position in symphonic literature. But at the same time, the things I learned from Mr. Varese — let us call them the horizons he opened up to me — have had a profound effect on the music I have written since.”

Still’s versatility as a composer is also evident in his chamber works and solo pieces. His Suite for Violin and Piano, for example, is a beautiful blend of classical and folk elements, each movement reflecting a different aspect of African-American culture. The first movement, ‘African Dancer,’ captures the rhythmic vitality of African dance, while the second, ‘Mother and Child,’ offers a lyrical and tender depiction of maternal love. The final movement, ‘Gamin,’ is a lively and spirited piece that showcases Still’s ability to infuse his music with character and personality.

In addition to his work in classical music, Still also made significant contributions to film and television scores. His work in Hollywood included scores for films such as Pennies from Heaven and Lost Horizon, and he served as a music advisor for Stormy Weather, a film that celebrated African-American musical talent. Despite the challenges of working in a predominantly white industry, Still’s talent and perseverance allowed him to break new ground and open doors for future generations of African-American composers.

Another important work in Still’s repertoire is Ennanga, a unique piece written for harp, piano, and string quartet. This composition, which draws its name from a traditional Ugandan harp, showcases Still’s ability to blend African musical elements with Western classical forms. The piece is a showcase of Still’s innovative spirit and his dedication to incorporating diverse cultural influences into his music.

Still’s chamber music also includes the notable Lyric Quartette, which consists of three movements, each representing different personalities one encounters throughout life. The first movement, ‘The Sentimental One,’ is characterized by its lush harmonies and lyrical melodies. The second, ‘The Quiet One,’ offers a reflective and introspective mood, while the final movement, ‘The Jovial One,’ brings an energetic and rhythmic conclusion to the piece. This work exemplifies Still’s mastery in creating chamber music that is both emotionally evocative and technically sophisticated.

In addition to his extensive compositional output, Still was a dedicated educator and advocate for the arts. He frequently lectured at universities and participated in various music festivals and conferences, sharing his knowledge and passion for music with students and fellow musicians. His contributions to music education helped pave the way for future generations of African-American composers and performers.

William Grant Still’s music is a tribute to his extraordinary ability to transcend cultural and musical boundaries. By drawing on his rich heritage and blending it with classical forms, he created a body of work that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. His legacy continues to inspire and influence musicians and composers today, ensuring that his voice will be heard for generations to come.

Still’s dedication to his craft and his pioneering spirit have left a mark on the world of classical music that cannot go unnoticed. His compositions, filled with emotional depth and cultural significance, continue to be performed and celebrated around the world.

Through his music, William Grant Still has given a voice to the African-American experience and has made a lasting contribution to the rich tapestry of American cultural heritage.