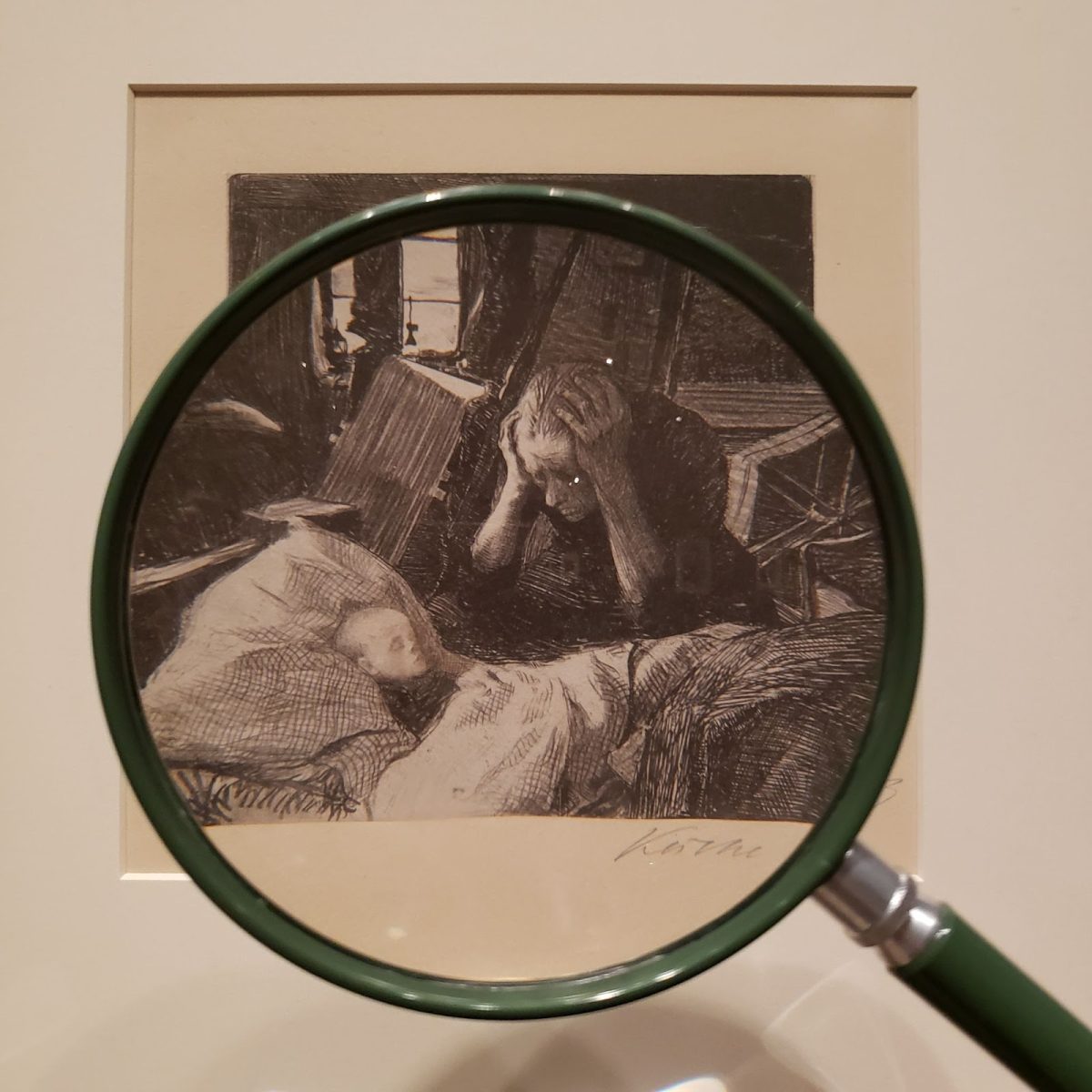

Walking along uncharacteristically dim walls of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), I hold up a magnifying glass to sunken faces, learning about their history in every etching. These faces reflect much of German society through World War I, the Weimar Republic, and World War II. An essential advocate for the impoverished, this is Kӓthe Kollwitz at the MoMA, currently on view through July 20th, 2024.

Exploring themes of poverty, motherhood, grief, and resistance, there is little balance in these harrowing depictions, no light at the end of the tunnel. In spite of this, they inspired action against injustices, giving hope where there was suffering. The MoMA is dedicated to displaying the astounding portfolio of the artist whose work was strikingly influential in a misogynistic society.

Experiencing the throws of social, international, and familial conflict, Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) had much material to draw upon for her pieces. Her commentaries, often depicted through famous works of writers, helped propel German movements for workers and women’s rights forward through their accessibility and steadfast insistence.

Socialist ideas swirled through Kollwitz’s childhood, congruent with the emergence of the political party. Her father was a social-democrat and her grandfather on her mother’s side was a Lutheran pastor who formed his own congregation after being expelled from the Evangelical State Church. Her family recognized her talent and enrolled her in painting lessons from an early age. The influences of religion and socialism resurface frequently in her prints.

Through her apprenticeships, Kollwitz was able to experience a multitude of art forms ranging from painting to sculpture, later in life focusing mostly on printmaking as her means of expression. Her education was supported by her parents, Karl Schmidt and Katharina Schmidt, who also shaped the motivation behind her art. Kollwitz originally trained as a painter. However, she shifted to printmaking because it lent itself to social criticism through its accessibility.

As a child, Kollwitz experienced the infant death of one of her brothers and witnessed her mother’s reaction to it, an event which deeply affected the way she perceived passing. She also suffered the death of her second son in the first months of the first World War, who enlisted underage. Maternal imagery from later in her career, such as The Mothers, Unemployment, and Pregnant Woman, drowning herself, take on struggles experienced in motherhood combined with economic hardships, reflecting the truth of many poor or working class families of the time.

Kollwitz was able to recognize and incorporate the multiple layers of melancholy that are faced in daily life. She could represent her emotions in images that draw the humanity and empathy of viewers, seeing the souls of the subjects as well as acknowledging the broader, more sterile, topics they fit into.

Despite being born into a progressive middle-class family, Kollwitz’s prints tend to depict the lower class. The compositions are diversely rich with depictions ranging from the clean-cut to more muddy representations, taking the grime of human touch (both through her subjects’ physical states and the inflections Kollwitz makes herself on her prints).

As a printmaker, Kollwitz’s art ran in cycles, and could be used in a commercial context. The easy reproduction of these pieces meant that every-day citizens could see them. Embracing the people she was advertising to, Kollwitz’s prints helped usher in rebellious ideology. The poor seeing themselves as courageous through Kollwitz’s prints shifted momentum in people from the educated elites to the larger workforce.

After watching a production of Gerhart Hauptmann’s play The Weavers in 1893 in which Silesian weavers rebel due to concerns regarding the Industrial Revolution, Kollwitz was motivated to begin one of her seminal cycles, A Weavers’ Revolt. However, while the play took place in 1844, Kollwitz made the story contemporary to depict workers of the time and show her concern for modern workers rights issues, with poor pay and decreasing jobs due to industrialization being the main concerns.

A storyline that involves the multiple faces of revolution is threaded throughout the pieces of this cycle, three being composed as lithographs and three as etchings. Moving from the clouded, scratched style of the lithographs, the etchings are sharp and more coherent. In this way, the prints themselves show the initial unknown nature of a revolt and its catapult into a defined status.

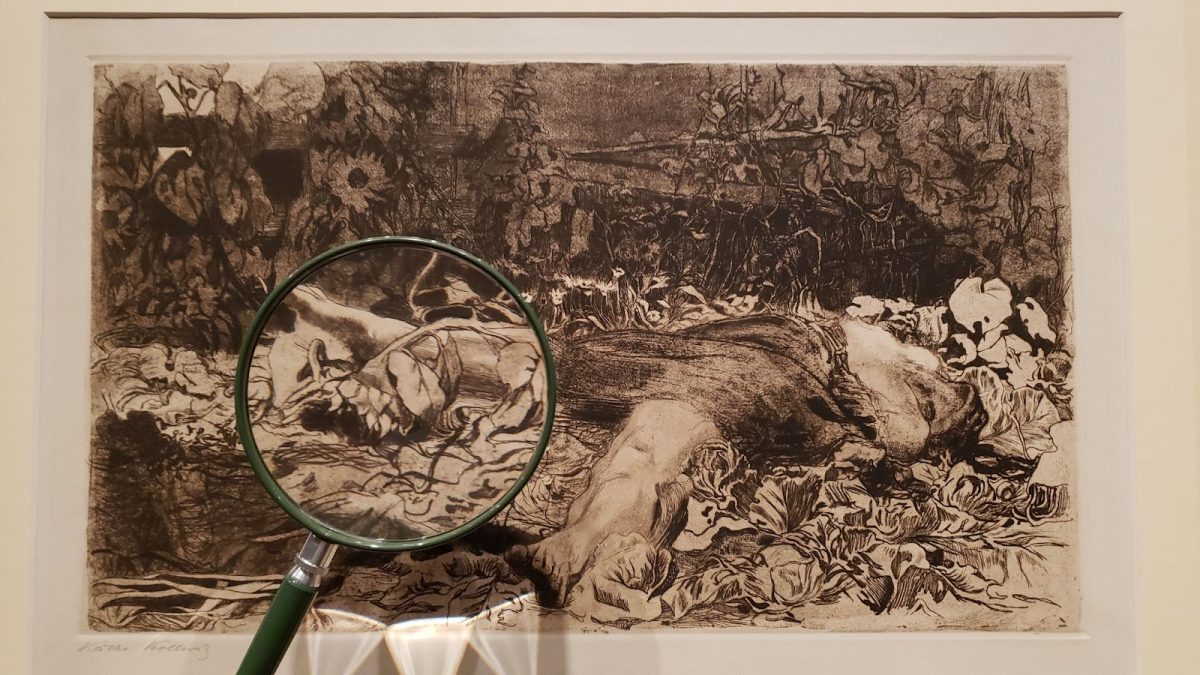

Highly contrasted works invite the reader to explore their many intricacies in face of the immense nature of their topics. Death, a common ally and consequence in the prints, is depicted as a relief rather than a terror.

Going from the suffering the weavers faced under their employers, to rising up against that oppression with dejected unease, to the suffering they face again for their audacity, Kollwitz perfectly summed up the grievances of many at the time. Although the cycle was received as a jab to the authorities of the time, it propelled Kollwitz into the spotlight as a respected artist.

From here, Kollwitz became a member of the Berliner Secession, a movement where artists withdrew from traditional presenting salons due to the restrictions imposed on contemporary art, and began work on her next cycle: Peasants War.

Inspired by Wilhelm Zimmermann’s Allgemeine Geschichte des großen Bauernkrieges, Kollwitz created a series of etchings depicting the causes and effects of the Great Peasants’ Revolt (1522 – 1525). A contemporary of her father, Zimmermann was involved in liberal circles prior to the revolution.

Another series of six depictions, Kollwitz follows a chronological timeline in Peasants War, showing how fast circumstances can change. For this cycle, the urgency and rapid movement of the subject is acknowledged by the shift in detail and composition.

For instance, the arrangement of the print, The Ploughmen versus that of ‘Charge’ both represent very different stages. While in both pieces the subjects move from the right side of the paper to the left with purpose, ‘The Ploughmen’ consists of begrudging workers who, even through the page, the viewer can feel that they are trapped in their circumstances as they futilely pull their plow without oxen. However, ‘Charge’ disregards the stagnancy of paper, its characters racing with insatiable determination, spurred on by the revered ‘Black Anna’ the supposed heroine of the revolt. There is even a sense of direction with the figures of Charge collectively forming an arrow.

Through the exhibit, we learn that Kollwitz shied away from the elite art world, living in a working class neighborhood and having her studio next to her husband’s medical practice, where he helped the poor. Several times, the exhibit invites viewers to connect her work with the movements that they supported, rather than compartmentalize them. The pieces and the many drafts that came before stand out against the dark walls, and the MoMA provides magnifying glasses to viewers to be able to examine the intricate strokes of the artist.

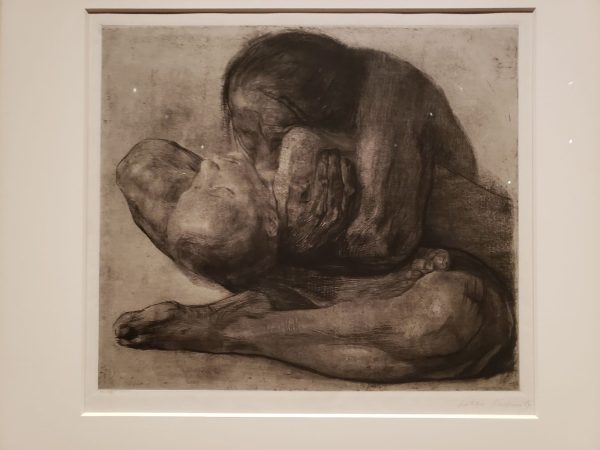

This appraisal is especially necessary when it comes to reviewing Kollwitz’s reconstructions. Over the course of her printmaking, Kollwitz would remake or reexamine pieces several times. One prominent example on display is Kollwitz’s ‘Woman with Dead Child’; in an almost Warhol fashion, six reconstructions, each slightly different, hang together in a wall of conceptualization.

Motherhood coupled with grief were themes which occupied much of Kollwitz’s efforts; after her son died in World War I, the guilt Kollwitz felt was immense and all-consuming. In an era accustomed to infant deaths, Kollwitz was still able to strike a nerve.

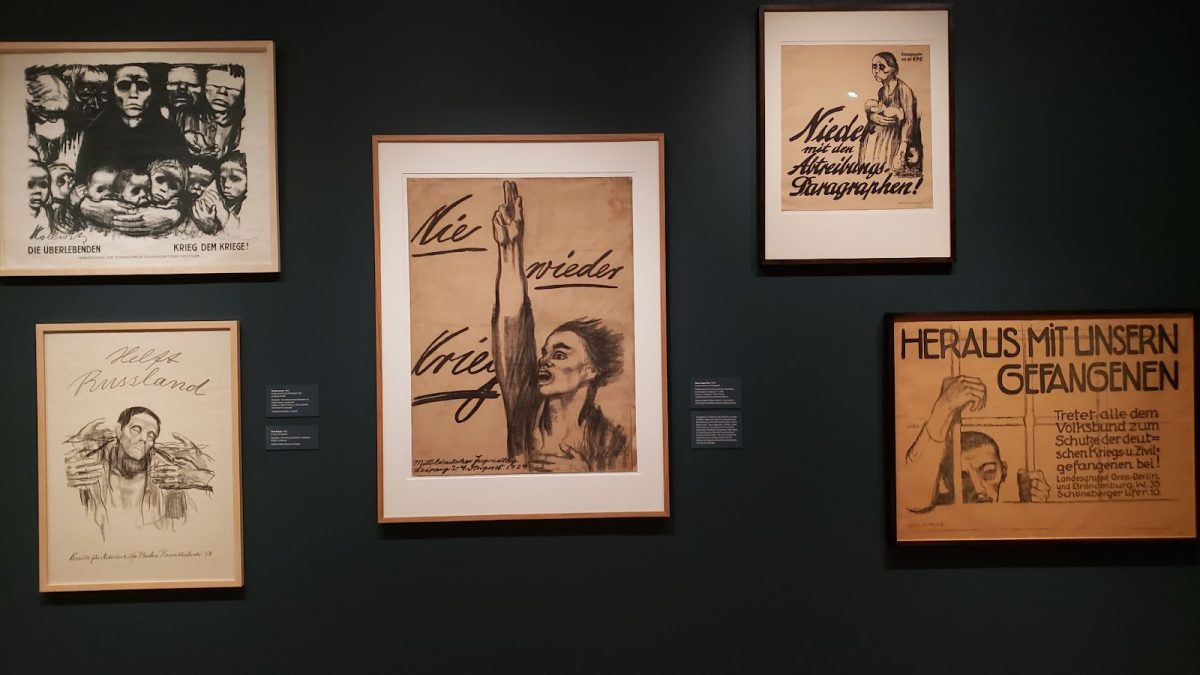

That was and still is, what Kollwitz’s art was aiming to accomplish: class consciousness. Others, specifically the poor, being able to understand their circumstances and what they could do to combat it was at the heart of Kollwitz’s prints. It is no surprise that the artist eventually turned to poster-making as a means of exposing the flaws within the system.

During the Weimar Republic, Kollwitz printed posters advocating against the problems she recognized utilizing phrases such as “Never War Again!” and “Germany’s Children are Starving” to grab attention. However she also knew who her audience was, and always included a striking depiction to convey the same message for those who could not read.

During Hitler’s regime, Kollwitz was targeted for her political activity, she was stripped of her teaching position at the Berlin Academy for Women Artists and the government threatened to send her to a concentration camp if she continued her advocacy. However, due to her international prominence, no action was taken against her.

As tumultuous as Kollwitz’s career was, her subject matter is summed up in digestible bites that intrigue viewers and leave them wanting to learn more about the artist in the exhibition. Despite its distressing material, the raw emotional connection Kollwitz makes with her prints leaves an impression, even decades later.

For the MoMA, this exhibit confirms that the oscillation of Kollwitz’s popularity in modern media is not the definition of her importance, but rather the ability for her to be a comfort in times of unease.

Kollwitz’s art was aiming to accomplish: class consciousness. Others, specifically the poor, being able to understand their circumstances and what they could do to combat it was at the heart of Kollwitz’s prints.