As the echoes of the past intertwine with the strides of the present, the art of Baroque historical performance stands not merely as a revival, but as a revelation. This musical rebirth, led by dedicated musicians with one foot in history and the other in contemporary practice, breathes new life into centuries-old compositions, challenging our notions of musical authenticity. As they wield instruments crafted in the image of their ancient predecessors, these performers invite us to a profound exploration: what did the musical world really sound like when Bach first set bow to string? This pursuit transcends simple historical curiosity, asserting its relevance in today’s cultural dialogue and promising a richer understanding of both past and future musical landscapes.

Music of the Baroque Period

Claudio Monteverdi, the emblematic figure of the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque era, fundamentally reshaped the musical landscape of his time through innovative approaches to composition and vocal expression. His adeptness at blending the lush polyphony of the Renaissance with emerging Baroque sensibilities defined a new era in music, characterized by dramatic expression and emotional depth. Monteverdi’s foundational works in opera, as well as his innovations in compositional form, are central to understanding his enduring influence.

Monteverdi’s embrace of monody marked a significant departure from the complex, layered textures of Renaissance music. Monody — featuring a single vocal melody line supported by simple instrumental accompaniment — allowed for greater emotional expression and clarity of text. This was revolutionary in an era when music was predominantly polyphonic, with multiple independent voice parts. Monteverdi’s use of monody is best exemplified in his stile recitativo, a technique that mimics the rhythms and pitch fluctuations of speech, enhancing the dramatic impact of the libretto. This approach was revolutionary, as it moved away from the sung melody of madrigals to a more spoken delivery, which would become a cornerstone of opera.

Monteverdi was a chief proponent of the stile moderno, or seconda pratica, which he defended robustly against critiques from traditionalists like Giovanni Artusi. This new style prioritized the emotional delivery of the text over the strict counterpoint and harmony rules that dominated Renaissance music. In his preface to the Fifth Book of Madrigals, Monteverdi articulated the principles of seconda prattica, arguing that the rules of music could be stretched to serve the expressive needs of the text. This approach was not only a defense of his evolving style but also a bold declaration of the potential for music to convey human emotion more directly and powerfully.

Monteverdi’s forays into opera are embedded into some of his most influential works. “L’Orfeo’, one of the earliest operas still regularly performed today, showcases his mastery of both monody and the stile recitativo. Through L’Orfeo, Monteverdi explored the power of music to narrate a story and express deep emotions, setting a new standard for the emerging genre. His later opera, L’incoronazione di Poppea, pushed these ideas even further, offering a more complex interplay of characters and motivations, and highlighting his innovations in orchestration and structure. These operas not only solidified the form of opera but also demonstrated its potential as a vehicle for dramatic and emotional expression.

Beyond opera, Monteverdi’s influence extended into other forms of music, most notably in his “Vespro della Beata Vergine“, commonly known as the Vespers. This work, monumental in scope and ambition, blends tradition with innovation, weaving intricate Renaissance polyphony with the dramatic, expressive monodic style. It demonstrated Monteverdi’s unique ability to fuse the old with the new, creating a richly textured yet emotionally resonant piece.

His numerous books of madrigals further illustrate the evolution of his musical style. Across these collections, Monteverdi’s progression from the Renaissance style of his early works to the more expressive, varied approaches of his later madrigals can be observed. These pieces served as both reflections of his personal artistic development and as markers of broader shifts in musical composition.

Monteverdi’s career reflects a profound understanding of music’s potential to evoke and enhance human emotion. His contributions to monody, stile recitativo, and opera, along with his pivotal role in developing the stile moderno, establish him not merely as a composer of his time but as a foundational figure in the history of Western music. His works, from the groundbreaking “L’Orfeo” to the influential Vespers and beyond, continue to be celebrated for their inventive blending of musical and textual expression, ensuring his place in the canon of great classical composers.

The Baroque era was marked by vivid regional differences that played a crucial role in the diversification and development of Western classical music. Composers across Europe tailored their musical expressions to reflect local tastes, religious contexts, and royal patronage, creating distinct styles that characterized the music of their respective regions. This period saw an intertwining of music and cultural identity, where each locale’s contributions enriched the broader tapestry of Baroque music and laid foundational elements that would influence subsequent generations of composers. From the opulent courts of France to the vibrant chapels of Italy and the theaters of England, these regional disparities fostered a rich diversity of styles and innovations, driving the evolution of music throughout the Baroque period.

Arcangelo Corelli exemplified the quintessential Italian Baroque style, which emphasized melodious lines and ornate, expressive ornamentation that catered to the virtuosic capabilities of performers, especially evident in string music. Corelli’s contributions, particularly his “12 Concerti Grossi, Opus 6,” advanced the development of violin techniques and the concerto grosso form, which featured a small group of solo instruments set against a larger ensemble, creating dynamic contrasts. His style, rooted in clarity and balance, significantly influenced the sonata form, focusing on the harmonic progressions that prefigure classical tonality. Corelli’s music typically showcased the emotional depth and technical prowess of the performers, setting a standard that would define the Italian string tradition.

Similarly, Barbara Strozzi, one of the few female composers of the time, made significant contributions to the cantata form, primarily focusing on secular themes. Her “Arias, Opus 8,” published in 1664, showcases her exceptional ability to convey emotional depth and nuanced expressions through her compositions. Strozzi’s work is marked by its melodic richness and expressive, often dramatic, vocal lines, which brought a new level of emotional intensity to the cantata form.

Jean-Baptiste Lully, who brought a markedly different approach in France, merged Italian operatic influences with the traditional French love for dance to create the tragédie-lyrique. This genre was characterized by the French overture, ballet interludes, and an emphasis on dramatic and lavish stage spectacles that mirrored the grandiosity of Louis XIV’s court. French music under Lully was less about individual virtuosity and more about reinforcing the monarchy’s splendor and political imagery. Lully’s work, such as “Armide,” incorporated the French penchant for clear declamation and lyrical elegance, emphasizing the drama and theatricality of opera. Tragically, Lully’s life ended in a peculiar fashion reflective of his passionate conducting style; during a performance, he struck his foot with the heavy conducting staff he was using, leading to gangrene which ultimately caused his death—a dramatic end fitting for a man whose life was devoted to the theater.

Henry Purcell in England integrated the clarity of an English text setting with the innovative European Baroque influences to create a style that was distinctly English. Purcell’s approach was noted for its eclectic blend, incorporating Italianate operatic elements and French dance rhythms while maintaining a uniquely English flavor through the use of folk tunes and a clear reflection of the English language’s rhythmic and melodic contours. His “Dido and Aeneas” and other semi-operas beautifully illustrate this synthesis, blending spoken dialogue with music — a form tailored to English tastes. Moreover, Purcell’s ability to navigate between sacred and secular forms, integrating complex counterpoints with emotional expressiveness, was uniquely adapted to the English baroque style, which was less about opulence and more about the dramatic and emotive potential of music.

As the Baroque period progressed into its later stages, figures like Antonio Vivaldi and George Frideric Handel not only continued the innovative traditions of their predecessors, but also introduced new elements that would profoundly influence the course of Western music.

Antonio Vivaldi epitomized the Italian Baroque style with his virtuosic use of the violin and his mastery of the ritornello form in concertos. Vivaldi’s work with the Ospedale della Pietà, a Venetian institution for the daughters of noblemen, provided him with an ideal setting to develop and refine his compositions, which were tailored to the skills of the highly talented musicians there. His most famous work, “The Four Seasons“, is a set of four violin concertos that are highly programmatic and depict scenes from each season, blending Vivaldi’s vivid musical imagination with his virtuosic command of the violin. This piece not only exemplifies his innovative approach to the concerto form but also demonstrates his ability to convey vivid imagery and emotion in music. “L’estro Armonico“, another significant work, influenced a wide range of composers across Europe, including Bach, and showcased his ability to infuse traditional forms with new vigor and complexity.

George Frideric Handel, on the other hand, moved from Germany to England, where he synthesized the Italian opera elements with German and English choral traditions, developing the English oratorio. Handel’s move to England marked a significant shift in his musical style as he adapted to English tastes, which were less enamored with the Italian opera than continental audiences. Handel’s innovation was particularly evident in his oratorios like “Messiah” (1742), which combine narrative depth, drawn from biblical stories, with the grandeur of opera but without staging. This format was immensely successful in England, where choral music had a strong tradition. Handel’s “Water Music” and “Music for the Royal Fireworks” are exemplary of his ability to compose music that not only entertained royalty but also resonated with the public, enduring as popular pieces in the concert repertoire today.

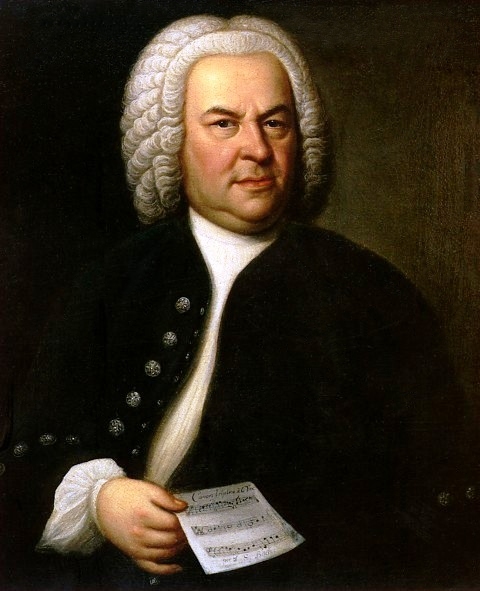

Johann Sebastian Bach stands as a colossus in the landscape of Baroque music, primarily through his sophisticated exploitation of contrapuntal techniques and his revolutionary approach to harmonic organization. His oeuvre spans both the sacred and the secular, with each composition not merely adhering to the stylistic norms of his time, but expanding them to new heights of complexity and expressive depth.

Bach’s music is quintessentially known for its intricate contrapuntal structure, which is most prominently displayed in works such as “The Well-Tempered Clavier” and “The Art of Fugue“. These compositions do not simply use counterpoint for complexity’s sake; rather, they explore and exploit the emotional and expressive capabilities of this technique. In “The Well-Tempered Clavier,” Bach takes the listener through a series of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys, a groundbreaking feat that not only demonstrated the practicality of the well-tempered tuning system, but also explored the unique character of each key in a systematic and deeply affecting way.

The “Brandenburg Concertos” showcase Bach’s ability to blend his rigorous intellectual approach with a vibrant array of forms and styles. Each concerto presents a different combination of instruments, creating distinct sonic landscapes that highlight both individual virtuosity and ensemble cohesion. For instance, Concerto No. 2 features a daring and high-spirited dialogue among trumpet, recorder, oboe, and violin, each part interwoven with remarkable finesse. This diversity not only reflects Bach’s deep understanding of each instrument’s capabilities but also his ability to integrate them into a cohesive whole without sacrificing the unique qualities of each.

In his sacred music, Bach’s use of intricate musical structures serves a higher liturgical purpose. Works like the “St. Matthew Passion” utilize the full spectrum of Baroque musical language — from the poignant, reflective arias to the robust, communal chorales — to engage listeners on an emotional and spiritual level. Bach’s setting of the scripture and other liturgical texts is particularly notable for how the music directly enhances the narrative and theological significance of the texts. For example, his use of dissonance, suspension, and resolution powerfully communicates the tension and release inherent in the passion story of Christ.

Bach’s compositional style is not merely a display of technical prowess but also a deep reflection of his intellectual engagement with the musical and theological themes of his time. His ability to infuse complex musical forms with deep emotional resonance is perhaps what sets his work apart in the Baroque canon. Bach’s music, characterized by an unmatched depth of expression and structural sophistication, has not only provided a model for future generations of composers but has also continued to offer rich materials for theoretical exploration.

Historically Informed Performance

The pursuit of historical performance practice is not merely a revivalist or academic endeavor; it represents a profound connection to our musical past, illuminating the scores of bygone eras with both scholarly insight and vibrant new life. This practice challenges musicians and scholars alike to delve deeply into the history of musical interpretation, seeking authenticity in the use of period instruments, phrasing, ornamentation, and even the composition of ensembles.

Historical performance practice, as a field, blossomed significantly during the late 20th century, with pioneering efforts aimed at reconstructing the sonic textures and expressive nuances that were likely familiar to the period’s musical intentions.

Historical performers often find themselves acting as both musicians and historians, interpreting scores not only with technical skill but with an understanding of the historical and cultural context in which a piece was created. This dual role is essential, as historical performance is not merely about recreating an antique sound but about understanding why composer’s from different eras wrote as they did. This understanding informs decisions about instrumentation, phrasing, and even the physical gestures of performance, all of which contribute to a more informed and expressive interpretation.

For contemporary audiences, historical performance opens a window to the past, offering a sound that is both educational and often startlingly different from the interpretations rendered on modern instruments. It also challenges performers to adopt techniques and philosophies that are sometimes counterintuitive, redefining their relationship with familiar compositions. Furthermore, this practice invites listeners to reconsider their expectations of musical performances, encouraging a deeper engagement with the music not just as an auditory experience but as a historically situated expression of human creativity.

One of the fundamental aspects of Baroque historical performance is the use of period instruments or accurate modern replicas. Instruments such as the Baroque violin, harpsichord, and natural trumpet differ significantly from their modern counterparts. For example, the Baroque violin uses gut rather than synthetic strings and lacks a chin rest and modern tailpiece, which affects both the method of playing and the quality of sound produced. Similarly, wind instruments from the Baroque era do not have the valves and keys that characterize modern instruments, necessitating a different technique from the players.

Tuning systems also play a crucial role. Baroque ensembles often tune to a lower pitch standard (A=415 Hz instead of the modern A=440 Hz), which affects the timbre and resonance of the music. Furthermore, the adoption of well-tempered or mean-tone temperaments, as opposed to equal temperament, impacts the harmonic color and dissonance resolution within pieces, aligning more closely with the composers’ original intentions.

Performers specializing in Baroque music invest considerable time understanding the intricacies of historical playing techniques. This includes the appropriate use of vibrato, which in the Baroque era was more of an ornament than a continuous tone enhancement, as well as mastering the art of ornamentation, such as the use of trills, mordents, and appoggiaturas. These components are often not fully notated in the scores and require performer discretion based on historical knowledge.

Articulation in Baroque music tends to be more detached than in Romantic or modern music, reflecting the dance-based rhythms and textures that permeate much of the repertoire. Phrasing, too, is guided by the rhetorical and speech-like qualities of the music, often described in treatises of the time as ‘speaking’ the music.

Baroque ensembles are typically smaller than modern orchestras, often consisting of one player per part in chamber works, which allows for a more intimate and conversational interaction between musicians. This setup is crucial for achieving the delicate balance and dynamic interplay characteristic of Baroque music.

Directors or leaders of these groups (often playing from within the ensemble, such as a harpsichordist or first violinist, unlike a modern-style conductor) work closely with the musicians to shape the interpretation of the music, relying on a deep understanding of Baroque gestures, dance forms, and rhetorical devices that inform timing, dynamics, and emotional expression.

This renewed interest in Baroque authenticity has been championed by historical performance ensembles, who strive to recapture the original essence of the era’s music. Juilliard415, based at the Juilliard School in New York, exemplifies the integration of historical performance practice within a major educational institution. Established as part of the school’s Historical Performance program, Juilliard415 provides students with the opportunity to explore a wide repertoire from the Renaissance to the early Romantic period on period instruments. Under the guidance of distinguished faculty and visiting directors, the ensemble not only studies but also performs works as the composers intended, using techniques and instruments appropriate to each era. The ensemble’s commitment to authenticity extends to collaborating with specialists in Baroque dance and rhetoric, thus enriching the performers’ understanding and execution of the music’s historical context.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Les Arts Florissants is one of the most revered Baroque music ensembles in the world. Founded in 1979 by William Christie, an American-born conductor and harpsichordist, the ensemble specializes in the performance of Baroque music on period instruments, with a particular focus on French repertoire. Les Arts Florissants plays a pivotal role in the revival and performance of 17th and 18th-century music, often bringing neglected works to light. Their performances are noted not only for their musical excellence but also for their meticulous attention to the stylistic nuances of the Baroque period, which Christie champions with zeal.

The meticulous art of historical performance practice transcends mere replication of Baroque music; it reanimates the philosophical and aesthetic spirit of an era. This approach involves a profound re-engagement with the historical context that shaped the compositions, employing period instruments and forgotten techniques to uncover the authentic sounds that once filled the courts and churches of Europe. In doing so, it challenges our modern perceptions of music as a static art form and redefines it as a dynamic dialogue across the ages. Each recital becomes a scholarly exploration, each concert a lecture in resonance, inviting audiences to listen not just with their ears but with their intellect. This revitalization of Baroque music underscores a broader cultural reverence for historical understanding, reminding us that to look back through the lens of history is to see the reflections of our future.

As the echoes of the past intertwine with the strides of the present, the art of Baroque historical performance stands not merely as a revival, but as a revelation. This musical rebirth, led by dedicated musicians with one foot in history and the other in contemporary practice, breathes new life into centuries-old compositions, challenging our notions of musical authenticity.