Amidst Manhattan’s vibrant Lower East Side, lies a beacon of visual storytelling: The International Center of Photography (ICP). For the last five decades, since its establishment in 1974, the ICP has served as a testament to the transformative power of the image, having illuminated the pivotal role of photography and artistic expression in facing our history.

Opened on January 24th, 2024, and on view through May 6th, 2024, the ICP at 50 exhibit invites visitors to celebrate the institution’s 50th anniversary with an optical journey through the past, present, and future. Featuring works dating from 1845 all the way up to 2019, from photographers known and unknown, the curated collection impressively spans centuries of photographic evolution in a mere two floors.

When I visit an exhibit, I tend to find that wandering aimlessly produces an optimal experience, allowing me to bask in the spontaneity of discovering works in whatever order I please. However, upon entering The ICP at 50 exhibit, this instinct seemed to immediately falter, as I found myself unable to resist the allure of following the exhibit’s delicately crafted narrative. Each photograph on display from the entrance to the exit is meticulously placed in chronological order, working to compose the historical tale of photographic and historical transformation at the core of the exhibit.

The visitor’s expedition begins in the 19th century, a time characterized by photographic experimentation and discoveries, with a collection of small tintypes, cabinet cards, and hand-colored studio portraits.

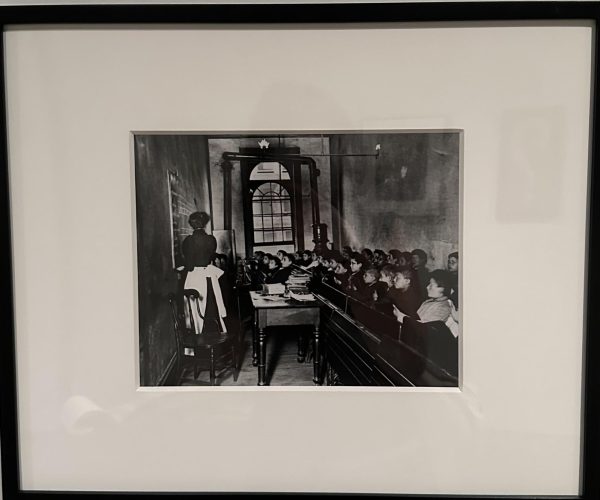

Photography in its earliest era, although devoid of color and often dynamic range, still managed to capture moments with an unparalleled level of emotion and intensity. Truthfully, in certain shots, the prominence of whites, blacks, and grays, only appears to heighten the weight of the depicted scene. For example, in Jacob Riss’s Public School Class in Essex Market School, ca.1890 the sharp contrast between the stark blacks and whites exacerbates the sheer darkness engulfing the scene, conveying how grim this classroom truly was. Like many of the others showcased at the exhibit, this photograph was taken with a single objective in mind – to act as an urgent wake-up call to the public. People were intended to be overcome with alarm and discomfort at the sight of this image and in turn a yearning to change the dire conditions present in it.

In the minds of many, photography is an art form intended to appeal solely to the eye – one that revolves around aesthetics and presentation. Yet, showcased at ICP at 50 are not the photographs that provoke a visual response, but rather those that ignite an emotional one. “These are photos that are not necessarily ‘beautiful’ but get us thinking about life in different corners of the world,” said Z., a visitor at the exhibition, with whom I spoke.

The ICP as a whole aims to embrace an esoteric side of photography, permitting the possibility of making viewers uncomfortable in pursuit of instilling a message within them. This is per the founder’s wish, Cornell Capa, who was devoted to “concerned photography,” a movement striving to make the image a catalyst for sparking change.

Within a single glance, a concerned photograph, while the scene it depicts is inherently static, perpetuates a dynamic story, leaving viewers no choice but to confront the often disturbing but urgent truths of our society. As Cornell Capa wrote in his novel The Concerned Photographer, “The Concerned Photographer finds much in the present unacceptable which he tries to alter. Our goal is simply to let the world also know why it is unacceptable.”

The ICP At 50 exhibit is no exception to the ICP’s articulated focus on concerned photography, making noteworthy commentary on an array of historical and current societal issues. Pressing themes of environmentalism, civil rights, and war are heavily incorporated throughout the exhibition, fostering a heavier but incredibly powerful viewing experience.

Notably, Fazal Sheikh’s Northwestern Frontier Province, 1997 touches on the devastation that fell over Afghan refugee communities preceding the Soviet-Afghan invasion. A man’s hand is pictured clutching a weathered image of his brother, who was tragically murdered during the war by Russian forces. This work is a fragment of one of Sheikh’s greater projects devoted to acknowledging how the grief inflicted by this conflict continues to plague Afghan people today. As a part of this project, Sheikh leverages the camera to construct narratives of individual loss and mourning with a collection of photographs depicting war survivors holding cherished pictures of deceased loved ones.

(Simone Ginsberg)

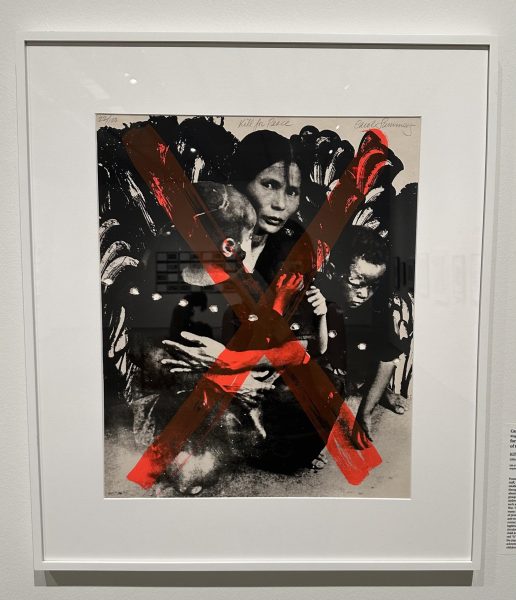

Carol Summer’s Kill for Peace, ca. 1967 continues to remark upon themes of war and violence, portraying a Vietnamese woman, a victim of the Vietnam War, clinging onto her two children, her eyes seething with piercing accusation and anger. Summer’s offers a visual representation of the destruction caused by war and militarism, urging viewers to humanize the phenomenon of “casualties of war,” in grasping that these “casualties” are not arbitrary statistics but real lives that were lost in the name of supposed peace.

As I progressed through ICP at 50, it became apparent why photography has been able to fuel political upheaval at such an unprecedented scale. The photograph is unique in its ability to trap any given moment in time, sealing the past, which can too often slip away, within the grasp of our collective memory. Emotions and memories, the seemingly intangible, can be captured in a single frame and preserved to be experienced by generations ahead. “The thing about photography is it has truth. These photos were of real things, events, and people. You can’t alter these shots. This is what happened. It’s difficult to encapsulate that in other art mediums,” said Jenny, another visitor with whom I had the opportunity to converse.

However, photography goes beyond what is captured by the camera, with personal touches from the photographer being just as integral to the art form as the photographs themselves. Photographers make calculated decisions to personalize the format, filter, or layout on a given photograph, ultimately to enhance a viewer’s perception of it. The ICP 50 exhibit does a fantastic job encapsulating this aspect of photographic art, showcasing a robust range of photographs with unique presentational and artistic choices.

For instance, while the entire composition of Summer’s Kill for Peace, ca. 1967 is undoubtedly striking, the gaze is inherently drawn to the artificial elements: the blazing red “X” and periodic rips across the poster. Both of these are described as “violent interruptions of the image,” acting as jarring symbols of the brutality of armed conflict.

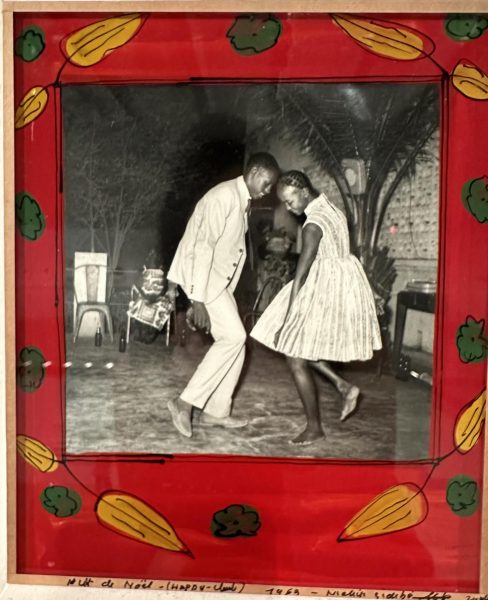

Even how a photograph is framed, although ostensibly insignificant, is reflective of the photographer’s intent and vision. In Malick Sidibe’s Nuit de Noel, 1962 the simple cardboard frame decorated with loosely drawn greenery is a pleasant contribution to the playful spirit of the work, perhaps making up for the absence of color. Indeed, when I asked Michelle, another visitor with whom I spoke, which photograph most stood out to her she almost instantaneously replied, “Definitely the one with the red frame. The evidence of the hand is really striking.”

The collection’s diverse range of photographic styles is not coincidental, stemming from its inclusion of a remarkably extensive list of photographers. ICP at 50 illustrates no shortage of renowned photographers, showcasing works taken by Jacob Riis, Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Weegee, Gordon Parks, Louise Lawler, Laurie Simmons, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, and numerous others. Amidst these famous works, what unequivocally captured my attention were those produced by unknown photographers. Scattered throughout the exhibit are numerous photographs credited to “unidentified photographers,” with a few even portraying “unidentified subjects.” These anonymous images enrich the exhibit with an unfiltered authenticity, being depictions of life in its rawest form – conservations of moments in history that might have otherwise been lost in the abyss of forgotten ones.

Walking through ICP at 50 almost leaves one with the sensation of traversing time itself, with each image encountered radiating the essence of distinct eras in both photographic and world history. It is truly an experience of witnessing history unfold. As there are 170 spectacular works included in this exhibition, I strongly advise anyone intrigued to go visit in person and immerse themselves in the full visual experience. Take the F train down to Essex Street and get a glimpse of how the photograph can yield the power to not only capture reality but also to intrinsically transform it.

Within a single glance, a concerned photograph, while the scene it depicts is inherently static, perpetuates a dynamic story, leaving viewers no choice but to confront the often disturbing but urgent truths of our society.