The Story of Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

With humor, irony, and simple prose, Kurt Vonnegut has secured his legacy as a classic postmodern American author.

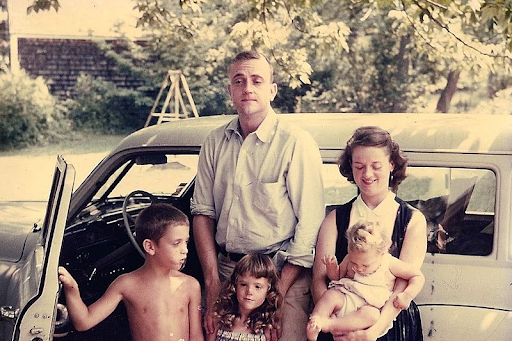

Here is Kurt Vonnegut pictured with his wife Jane and his children Mark, Edie, and Nanny (from left to right). (Photo Credit: Unknown; copyright held by Edie Vonnegut., CC BY-SA 4.0

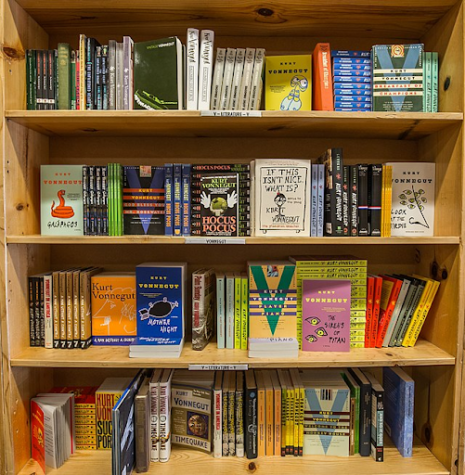

Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughter-House Five has been distinguished by many readers as a deliciously complex conglomeration of purposeful science-fiction, humorous satire, and gritty irony. It has also been challenged for removal at least eighteen times across public libraries and schools in the United States. So it goes.

The First Amendment in the Constitution is written as follows: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

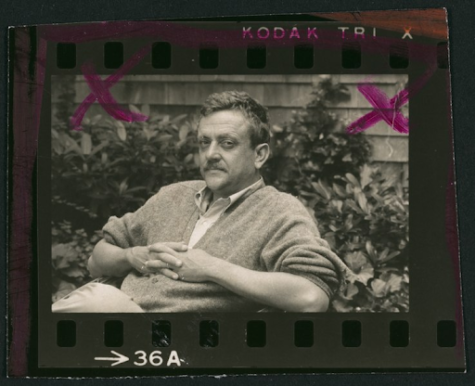

For Kurt Vonnegut, the infringement of this amendment was of serious contention. He found his duty as an author to be a watchdog of democracy. Vonnegut frequently regarded himself as a member of ‘the last recognizable generation of full-time, life-time American novelists,’ who were born in the hard-hitting time of the Great Depression and were raised by the ruthlessly cruel Second World War.

His novels have been targets of censure because many of them deal with dystopian aspects of our society. While the horrors of pet cemeteries and haunted houses are palatable to some, the truths of warfare, poverty, and mental illness are not. For example, Slaughterhouse-Five has the alternative name of The Children’s Crusade to demonstrate the youth of the soldiers that are shipped off overseas to be gunned down in disease ridden trenches.

Since his works were first published, Vonnegut had been pushing back on the censure of his novels throughout the United States. In a letter written to a school board in North Dakota that ordered the burning of Slaughterhouse Five, Vonnegut writes, “If you were to bother to read my books, to behave as educated persons would, you would learn that they are not sexy, and do not argue in favor of wildness of any kind. They beg that people be kinder and more responsible than they often are.”

Vonnegut’s novels, despite dealing with grim and often morbid topics, maintain what some may call hopeful pessimism. This kind of gritty honesty wrapped in satire and simple prose is Vonnegut’s gift to us. He may not always answer the Kantian question “What may I hope?” but Vonnegut offers us a glimpse of what our society may degrade to if we are uncaring and apathetic people.

As much of his literature is based on his experiences, Kurt Vonnegut Jr.’s life story is as backward, scattered, and nonlinear as his novels.

Before he was the face of the American literary counterculture, he was called ‘K’ by his family members and his close friends. Vonnegut claimed no tangible connection to his Kafka counterpart Joseph K., despite the shared nickname, as he claimed to know at all times who truly was in charge. “This could be a mistake,” Vonnegut remarked in response to his own claim.

And perhaps it was.

Vonnegut was born in Indianapolis as the youngest of three children to Kurt Vonnegut Sr. and Edith Vonnegut. His parents were descendants of German immigrants in the nineteenth century. His paternal great-grandfather, Clemens Vonnegut, founded the Vonnegut Hardware Company, while his grandfather and father pursued architecture. Vonnegut’s mother was part of the Indianapolis high society due to her family’s name, Liebers, being associated with a successful brewery.

Despite being of German descent, Vonnegut felt disconnected from his heritage. Being that he was raised in the wake of the First World War, Vonnegut quickly learned what it meant to prove patriotism: to be ignorant and rootless. The erasure of his German culture most visibly manifested in the transformation of his name: Vonnegut’s surname was derived from a forebear who had an estate- ‘ein Gut’- on the River Funne, hence the name Funnegut. However, this was too similar to the English “funny gut” and it was consequently changed down the family tree. Vonnegut felt as though being raised without the remnants of his family’s German traditions and histories was a serious injury, and regarded it as a ‘quiet burial of a culture.’

Down Vonnegut’s family tree, there are several failed creative minds muffled by the desperation of the time that was immediately before and after the Great Depression. His grandfather, Bernard Vonnegut, was one of his relatives who, despite not knowing him, Vonnegut resonated with deeply. Vonnegut’s family legend has it that Bernard was working at Vonnegut Hardware Company and began to cry. When asked what was wrong, he replied that he did not want to work in the store — he wanted to be an artist instead.

Bernard Vonnegut pursued architecture in New York City, and, against his will, was forced back to Indianapolis to be married. In regards to his grandfather, Vonnegut said, “The things that made him happy or sad were equally meaningless to his relatives and neighbors. So he became silent as a clam. He died.”

He continued: “He may even have been a genius, as mutations sometimes are.”

The same fate would be forced on Vonnegut himself, who, despite coming from a family of considerable wealth, would find himself with almost nothing to his name. His mother and father would eventually spend all the remaining capital from both their family’s wealth in efforts to live outwardly lavishly. A life of luxury was especially important to Edith Vonnegut, who was accustomed to such grandeur. When Vonnegut was forcibly enlisted as a private in the army, Edith’s stress regarding his welfare and her financial situation began to overwhelm her. In an attempt to procure some kind of income, she tried to sell some short stories she had written. This would prove futile, and she would pass away due to an accidental overdose of sleeping tablets.

Vonnegut’s father, Kurt Vonnegut Sr., lived as a recluse for ten years following Edith’s passing. He had developed a mindset that the Germans call ‘Weltschmerz’ — skeptical and fatalistic. He lived his last couple years in a last lap of luxury on what capital was left, with his favorite recordings of Mozart, Beethoven, and Richard Strauss. This antagonistic sort of behavior made it difficult for Vonnegut to maintain a healthy relationship with his father. Instead, he formed a valuable relationship with his father’s younger brother, Alex. Alex Vonnegut was a life insurance salesman and a socialist, and he often gave Vonnegut books such as Thornstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class.

While his family situation was dire, Vonnegut never felt any real connection to his material possession nor to his capital. Although his mother spoke of a time after the Great Depression in which the Vonneguts would return to their place in high society, Vonnegut found no interest in it. He preferred the company of his friends in his public school, and felt that if he had regained his wealth, he would lose what he considered ‘everything.’

Vonnegut spoke distastefully of an aggressively material lifestyle lived in ‘castles.’ In his public high school, one of his teachers had brought the following Henry David Thoreau quote to his attention: “I have traveled extensively in Concord.” Vonnegut admired the way that Thoreau captured a child-like wonder of the world. Vonnegut was content with his status of living because he felt that there was always more than enough to marvel at for a lifetime, despite what situation one might be born into. As for living in a castle, Vonnegut claimed, “Indianapolis was full of them.”

At this point, the Vonnegut river of wealth had gone dry. Vonnegut left his castles in Indianapolis and found himself enrolled in Cornell University. Under the pressure of both his father and his brother to study for a profession that was profitable, Vonnegut had studied Chemistry. Although he had a creative outlet at The Cornell Daily Sun, he despised his science studies. “I probably would have adored this hell hole if I had been allowed to study and discuss the finer things in life,” said Vonnegut in regards to his time at Cornell.

Ironically, at the end of Vonnegut’s time at The Cornell Daily Sun, he would write an editorial advocating for pacifism as the United States debated its entrance to the Second World War. This piece earned him an academic probation, and he was consequently dismissed from the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps.

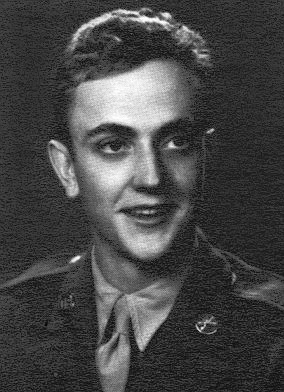

Although Bernard Vonnegut was able to evade the draft, it was unlikely that Vonnegut would be fortunate enough for the same fate. Instead of waiting to be drafted, Vonnegut enlisted himself. In March of 1942, he was relocated to Fort Bragg, North California to begin training. The young cadet was taught to man and maintain howitzers, which were long distance heavy artillery weapons effective in trench warfare. With training and instruction in mechanical engineering at The Carnegie Institute of Technology and the University of Tennessee under his belt, Vonnegut was sent to the front of the war in three months.

He was part of the 106th Infantry Division as an intelligence scout during The Battle of Bulge. The battle was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front, and it lasted five weeks towards the tail end of the Second World War. The “Bulge” was considered to be the third-deadliest military campaign in American history. Out of 610,000 American troops, there were 81,000 battle casualties and at least 8,400 soldiers were killed.

On the front, Vonnegut was a freshy faced youth who had flunked all of his mechanical engineering instruction. Like many others on the battlefield, he did not know the first thing about warfare. In fact, he found himself on the Western Front imitating various war movies he had seen in the theater.

His battalion scouting unit was captured by the German forces in Luxemburg. It was frigid from the snow, which covered their scant and drab uniforms in a gully made from the First World War. When they were captured, Vonnegut was placed in a box car with other soldiers and shipped off to Dresden. In abidance with the articles of the Geneva Convention, privates were required to work for their keep. At Dresden, he was employed by contract to a malt syrup factory.

Vonnegut described Dresden as “the first fancy city” he’d ever seen. There were scarcely any air raid shelters, nor were there any war industries. Instead, it was a city with statues and zoos, hospitals and clarinet factories.

On February 13, 1945, a siren went off in Dresden. In the slaughterhouse he was kept in, Vonnegut and other American soldiers found refuge in an underground meat locker while the city was inflamed by the allies. The Royal Air Force and the United States Air Army Forces had dropped more than 3,900 tons of high explosive bombs and incendiary devices, which destroyed more than 1,600 acres of the city and killed an upper estimate of 35,000 people.

Vonnegut and the captured soldiers in Dresden were ordered to dig into the basements of homes to collect corpses for sanitary reasons. Vonnegut described the scene as macabre: “When we went into them, a typical shelter, an ordinary basement usually, it looked like a streetcar full of people who’d simultaneously had heart failure.”

The dead were physically loaded onto wagons and mass burnings of bodies were conducted in large open areas such as parks. The search for bodies before they began to smell or spread disease was referred to by Vonnegut as a ‘terribly elaborate easter egg hunt.’ At a certain point, they would simply loot the dead bodies for valuable trinkets, before incinerating them directly underground instead of moving them.

When Vonnegut returned home, he applied to the University of Chicago with help from the newly passed G.I. bill. During the admission process, Vonnegut found himself being interviewed by one of the people who ordered the Dresden bombing. He recalls the officer saying, “Well, we hated to do it.”

At first, Vonnegut felt as though his experiences at Dresden were too minor to form a coherent war novel. He attempted to research the event in The Indianapolis News and only found a short piece which said that two planes were lost when they flew over Dresden. Vonnegut shamefully recalled being envious of others who had ‘better’ war stories to share: “I remember envying Andy Rooney who jumped into print at that time; I didn’t know him, but I think he was the first guy to publish his war story after the war; it was called Tail Gunner. Hell, I never had any classy adventure like that.”

However, inspiration for Slaughterhouse-Five sparked when Vonnegut had read a book about Dresden by David Irvin which declared the bombing the largest massacre in European history. Because Vonnegut’s own experiences in warfare had been humiliating, he naively believed in a sensational image of heroic patriotism. He envisioned his novel to star big shot celebrities such as John Wayne and Frank Sinatra.

It was only until the wife of a fellow captive at Dresden sobered him of the true reality of war that Vonnegut found himself crafting a truly anti-war novel. She told Vonnegut, “You were just children then. It’s not fair to pretend you were men like Wayne and Sinatra and it’s not fair to future generations because you’re going to make war look good.” Vonnegut found this reminder to ‘free’ him from the confines that dictated how war should be discussed. He recalls that when he was a prisoner of war, he was still baby faced, and only shaved once in a blue moon.

From Vonnegut Hardware Company in Indianapolis to the Western Front in Europe, Kurt Vonnegut’s experiences have shaped his contributions to contemporary literature in the form of short stories and novels.

In Vonnegut’s first novel Player Piano, for example, he demonstrates a weary antagonism toward the ever growing role of technology in our society. The novel was inspired by his work at the company General Electric, where he had seen the capabilities of automation in replacing human labor. In Player Piano, technocratic engineers serve as the ruling class instead of the classic Marxist capitalist. In this dystopian society, automation has completely eliminated the need for human labor, forcing people to live in abysmal slums. Player Piano is undoubtedly a very straightforward and conventional science fiction novel, as it was Vonnegut’s debut into literature. Although it stylistically lacks the fantastical creativity and quirky satire that defines Vonnegut’s writing, it still remains as a valuable contribution.

The triumph of Player Piano is that there truly is no triumph at all. At the end of the novel, the proletariat from the slums form a revolution against the machines which make them subservient. However, this revolution fails even when they’ve destroyed many of the existing machines. Ironically, the revolutionaries begin to tinker with the very machines they destroyed with the purpose of liberating themselves. They are thus subjected to an inescapable cycle of oppression and liberation.

In Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut carefully constructs his portrayal of soldier Billy Pilgrim to maintain this critical hopeful pessimism. Despite being about war, the novel does not follow the conventional plot line driven by a hero’s adventure. Billy Pilgrim is not a hero. Nor does he need to be.

Billy Pilgrim has no triumph. He does not return from the front adorned with medals, accomplishments, or cinema worthy bravery. Billy instead returns with a two carat diamond he had looted from a German corpse in a basement in Dresden.

This portrait of a protagonist that lacks conventional heroic qualities emphasizes the meaninglessness of war. There are many more Billy Pilgrims and Kurt Vonneguts who, in battle, contribute absolutely nothing to winning a war. And the question remains, is this truly a fault? In fact, Billy Pilgrim remains as a critique of what it truly means to be a hero in a circumstance as inhumane as war. Vonnegut uses humor and surrealism to portray the rest of Billy’s life in a comedic way in which he dies absurdly at the end.

But despite this pessimistic view of our society, Vonnegut gives us a glimmer of hope. The notion of becoming ‘unstuck in time’ consequently turns over the idea of linear time that we’ve created for ourselves. Instead of a linear stream of events, Billy is able to experience his life in a rather cyclical manner. Death doesn’t always come last, birth doesn’t always come first. Even in the direst of circumstances, like being a prisoner of war, Billy is able to call upon the past for comforting experiences. Vonnegut deconstructs the typical structures we have confined ourselves to that prevent us from accomplishing maximum human capability in Slaughterhouse-Five.

While Kurt Vonnegut is fierce in his critique of humankind’s shortcomings, he still remains hopeful in the power of the human spirit even in the darkest of times.

While Kurt Vonnegut is fierce in his critique of humankind’s shortcomings, he still remains hopeful in the power of the human spirit even in the darkest of times.

Karishma Ramkarran is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Observatory’ yearbook and a Staff Reporter for 'The Science Survey' newspaper. She appreciates journalistic...