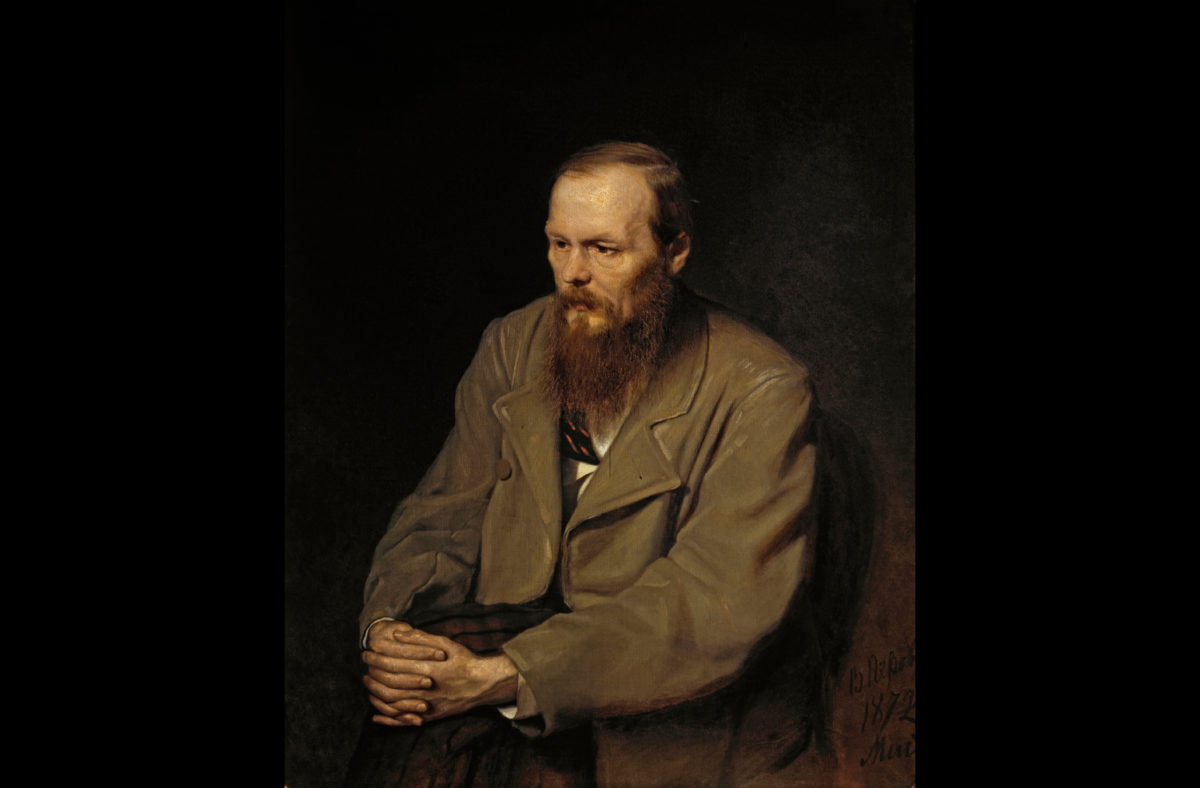

The Dark Times of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky’s literary genius shines through in key works such as ‘Crime and Punishment’ and ‘The Brothers Karamazov.’ Still, it is his life and broader historical and artistic influence that fashion him into a true literary great.

On a rare visit to a museum in Basel, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky looked at Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, which depicts an emaciated Christ covered in plum purple bruises, dried blood, and the beginnings of bodily rot. “One could lose one’s faith from that picture,” Dostoevsky remarked to his wife Anna, who quickly dragged him away, worried that her agitated, overwhelmed husband was on the verge of an epileptic seizure.

This grotesque image and Dostoevsky’s fascination with it (he insisted on looking again before they left) is emblematic of this literary genius’s fascination with suffering. While Anna was revolted by the audacity to subject Christ to a state of physical decomposition under the painter’s hand, Dostoevsky was convinced that it was Christ’s proximity to decay which lent meaning to his sacrifice for humanity. In Dostoevsky’s mind, it was his suffering, as evidenced by his mortal body, which granted him a godly status.

It would be this line of thought, revolving around nature and implications of suffering, that would inspire many of Dostoevsky’s masterpieces, including The Idiot, Crime and Punishment, Notes from the Underground, and most famously, The Brothers Karamazov. Packed with painterly psychological portraiture, infused with radical ideology, and threaded with untenable tensions, his prose illuminates the human heart along with the garden in which it achieves sanctification through the interminable exercise of its own mercurial will.

Dostoevsky’s own life – dampened by darkness – taught him the tragic tune he weaved into his works. Born in Moscow in 1821, he was quickly exiled from the primordial paradise of family life at fifteen when his mother, Maria Fedorovna Nechaeva, succumbed to tuberculosis during her ninth pregnancy. Dostoevsky and his brother Mikhail were soon sent to the St. Petersburg Military Engineering School where they learned that their father, Mikhail Andreevich had died a mere six months into their education.

Andreevich, a former military surgeon, frequently exhibited drunken episodes of violence which prompted his serfs to murder him by pouring vodka down his throat until he choked. Eerily foreshadowing the seismic social shifts which would befall Russia in the coming decades, this murder remained a guarded family secret. It was the sinister nature of this tragedy that numerous scholars speculate both brought on Dostoevsky’s epilepsy and catalyzed his creative awakening by plunging him into the dramatic depths conducive to literary genius.

After spending six years at the military engineering school and completing one mandatory year of service, Dostoevsky published his first novel Poor Folk (1846), the tragic story of a tumultuous relationship between a young clerk and a seamstress narrated through the exchange of fervent, loving letters. This novel facilitated his rise to stardom and prompted writers like Nikolai Nekrasov and Vissarion Belinsky to dub him as Russia’s ‘next Gogol.’

His next novel garnered less praise but unveiled his talent for psychological probing, revealing why Nietzsche declared that “Dostoevsky was the only psychologist from whom I had anything to learn.” The Double chronicles the persecution mania of a weak, haughty clerk, Golyadkin, whose sanity succumbs to a pervasive fear that his doppelgänger is orchestrating a grand conspiracy against him. Eventually, Golyadkin is driven to the madhouse where deleterious delusions and even his own reflection torment him.

Insanity is the central vein which carries the lifeblood of Dostoevsky’s great works. Earning the title of “The Shakespeare of the asylum,” Dostoevsky offers psychological case studies in the calculated portrayal of characters plagued by psychosis, brain fever, violent emotional paroxysms, and a plethora of other invisible, deadly mental wounds. From Raskolnikov’s moral uncertainty and societal alienation to Ivan Karamazov’s feverish and fantastical encounter with the “devil,” Dostoevsky’s pen bleeds with fervent feeling, flirting with sin and conveying the disturbing idea that we are all seated on the edge of a mental cliff from which descend bottomless depths of instability and insecurity.

It is Dostoevsky’s obsession with the anxiety at the heart of the human experience that has inspired innumerable psychologists and philosophers. Freud believed that The Brothers Karamazov was “the most magnificent novel ever written,” Sartre was enamored with Dostoevsky’s piercing words, and Albert Einstein believed that it was Dostoevsky who granted him the most insight into the instability of reality.

While Dostoevsky began suffering from epileptic attacks after the death of his father, his psychological fascinations truly took root following his arrest for involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle, a revolutionary group that discussed societal issues and various controversial works of art. In 1849, he, along with approximately 34 of his associates, was arrested for alleged subversion against Tsar Nicholas I. In prison, Dostoevsky was subjected to solitary confinement; guards even wore velvet-soled shoes as they marched past his cell. Eight months later, he was condemned to death and taken before an execution squad. At the very last second, when the fear-stricken men counted their every last heartbeat, one of the Tsar’s soldiers announced that the sentence would be commuted to a more lenient one in light of the prisoners’ youth.

Dostoevsky describes the event in an inspiring letter to his brother Mikhail. He wrote: “Today, December 22, we were driven to Semyonovsky Parade Ground. There the death sentence was read to us all, we were given the cross to kiss, swords were broken over our heads, and our final toilet was arranged (white shirts)….. I remembered you, my brother, and all yours; at the last minute you, you alone, were in my mind, and it was only then that I realized how much I love you, my dearest brother!” Later he adds: “Brother, I’m not depressed and haven’t lost spirit…. Not to become depressed, and not to falter – this is what life is, herein lies its task.”

Dosteovsky’s harrowing experiences in prison catalyzed his creative awakening. In The Idiot, Prince Myshkin tells the story of a condemned friend whose death sentence was reversed, describing how the prisoner was fraught with the realization that should he have more time, he would “turn every minute into an age.” Moreover, in Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky draws from his own experiences with interrogations preying on the ignorance of the accused to convey a pitiful scene of the questioning of Raskolnikov, the novel’s protagonist. Not tempted to taste the addictive lotus of eternal despair, Dostoevsky assumed the belief that prison, above all else, was the ultimate artistic agitator.

Still, his odyssey did not end there. Dostoevsky, shackled with ten pound irons on his feet, was sent to Siberia where he completed four years of prison labor. During these lost years, he wrote nothing, but gained the experience which would inspire Raskolnikov’s own journey in exile, characterized by the dawn of the idea that living is a physical act that cannot be solely subject to philosophical assessment. During his subsequent five years of required military service in exile, he read voraciously and married Marya Dmitrievna, whose mercurial temperament occupied the liminal space between stormy love and passionate hatred.

Dostoevsky was disloyal to his wife, commencing an affair with a 22-year-old student, Apollinaria Suslova, who confessed her love in a letter to her then 40-year-old teacher. Apollinaria, a staunch feminist, frequently demanded that Dostoevsky abandon his ailing wife, laying the groundwork for the tumultuous loves laid on a minefield of misfortune in his most seminal works. After his wife’s death, Dostoevsky proposed to Apollinaria who refused him and burned many compromising letters that narrated their secret romance.

In 1859, he returned to St. Petersburg where he collaborated with his brother Mikhail on two journals Time (1861-1863) and Epoch (1864-1865) which centered around the ideal of Russians promoting authentic Russian as opposed to Western culture. He also hoped for a return to the native soil, depicting cities as Towers of Babel in Notes from the Underground and declaring that children should grow up in edenic gardens, not factories which deaden “their minds before some common machine to which the bourgeois says his prayers” and “ruin their morals through the depravity of the factory, which is such as was never seen in Sodom.” Here lies the evidence – the deep-seated sympathy with the impoverished working class – which encourages many scholars to crown Dostoevsky as a revolutionary, potentially Marxist figure. It is rumored that Stalin regularly read and annotated (in a blue and red colored pencil) The Brothers Karamazov.

After the tragic death of his brother, Dostoevsky was left financially burdened and thus returned to his writing in hopes of attaining a larger fortune. In his vaguely autobiographical novel Notes from the House of the Dead, Dostoevsky recounts the experience of Alexander Petrovitch Goryanchikov, a nobleman who is sent to a Siberian prison camp after brutally murdering his wife. In confinement, he undergoes a radical transformation; despite facing the class hatred of his fellow inmates, he eventually recognizes the masses of the Russian poor as a source of spiritual strength. Dostoevsky threads this idea through numerous of his masterpieces, convinced that the emancipation of the serfs would enable Russia to become a more united nation.

In 1866, Dostoevsky released Crime and Punishment, a literary gem whose hero is Raskolnikov, a law-school dropout who is “remarkably good-looking,” and relies on monetary support from his mother and sister. Seeking to ameliorate his poor financial situation, he orchestrates the perfect crime, the murder of an old, bitter pawnbroker who he believes to be a “pernicious louse” that nobody will cry a river for in her absence. Still, the perfect crime quickly faces complications when the pawnbroker’s half-sister stumbles upon the bloody scene, forcing Raskolnikov, in a fit of feverish fear, to murder her as well.

Having stolen the pawnbroker’s purse, Raskolnikov buries it in a courtyard and returns to his home where the fabric of his mind unravels in a sequence of disorienting dreams and hellish hallucinations. Eventually, he confesses his crime to Sonya, a prostitute who possesses “insatiable compassion,” worrying only about the state of Raskolnikov’s soul and embracing him with warmth when he tells her of his terrible crime. Sonia urges Raskolnikov to repent, declaring: “Go at once, this minute, stand at the crossroads, bow down, first kiss the earth which you have defiled and then bow down to all the world and say to all men aloud, ‘I am a murderer!’ Then God will send you life again.”

Raskolnikov obeys and is sent to prison in Siberia. While this story is hailed as a testament to Dostoevsky’s genius, Vladimir Nabokov, the famous author of Lolita, Ada, and Pale Fire, detested the “ghastly” Crime and Punishment. “Non-Russian readers do not realize two things: that not all Russians love Dostoevsky as much as Americans do, and that most of those Russians who do, venerate him as a mystic and not as an artist. He was a prophet, a claptrap journalist and a slapdash comedian. I admit that some of his scenes, some of his tremendous, farcical rows are extraordinarily amusing. But his sensitive murderers and soulful prostitutes are not to be endured for one moment — by this reader anyway,” Nabokov commented in a 1964 interview.

Nabokov’s claims are highly contentious; while the “sensitive murderers and soulful prostitutes” appear artificial to Nabokov, he fails to recognize how Dostoevsky reconciles the contradictions that lie at the heart of human character and the conflicting feelings aggravated by destitution, moral confusion, and psychological suffering. Intimately acquainted with violence and suffering, Dostoevsky developed a style that gravitates towards extremes. He paints a vivid portrait, alternating in the shifting light, which unveils Raskolnikov’s soul with the strained pain of revealing a well kept, incendiary secret. We see Raskolnikov as a despicable beast, capable of numbing himself to moral feeling and brutally murdering an old woman “without effort” and without being “conscious of himself.” We then see Raskolnikov’s guilt materialize in a Shakespearean parallel to Macbeth as he cannot shake the fear that “all his clothes were covered with blood, that, perhaps, there were a great many stains, but he did not see them.” We watch — suspended in stillness — as he gives his last 20 roubles to a widow, Katerina Ivanovna, who is struggling to feed her family. We watch, sympathy seeping into our cold hearts, as he casts himself as a criminal in Sonia’s pure eyes. What Nabokov ignores is the fact that Raskolnikov belongs to the select group of “sensitive murderers” while also being cold, unforgiving, and morally decrepit. Dostoevsky’s hero is a man of extremes and thus burns brilliantly under the white light of truth.

Moreover, beyond the “tremendous, farcical rows” lie profound social and philosophical questions that Dostoevsky poses in contemplation of the maddening mood of his tumultuous time. He evaluates the “educated criminal” as a means of analyzing the educated revolutionaries who were sowing the seeds of discord which would culminate in the Russian Revolution in 1917. Dostoevsky writes that the “educated criminal” is the moral transgressor “with a conscience, with awareness, heart. The pain in his heart will be enough to do away with him, long before any punishment is inflicted upon him.” Similarly, the revolutionaries that the tsarist regime labeled as unprovoked, unscrupulous insurgents, Dostoevsky understood to be directed by a strong, collective moral compass, to be moved by sympathy, hope, suffering, and love. He uniquely sympathized with Raskolnikov and the revolutionaries, perpetually questioning the depths to which men could descend before entering morally dark territory.

He also recognized their ‘crimes’ as the product of a theory of egoism which infused the Russian air, prompting individuals to attempt to achieve sanctification through the realization of their own will. In Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky crafts a world in which good and evil cease to be binary and consequently, in which men degenerate to the point of absolute degradation. By weaving a distinctly philosophical flair into his masterpiece, Dostoevsky examines the extent to which radical ideology can shape individual behavior.

The Gambler closely followed Crime and Punishment and was inspired by Dostoevsky’s experiences as a compulsive gambler (which led him to lose all the rights to his future work to his publisher at one low point). The following year, he married his second wife Anna Grigorevna Snitkina, a twenty-year old stenographer who was helping him by writing down his drafts. Deeply moved by Dostoevsky’s exemplary prose even before meeting her enigmatic husband-to-be, she wrote that upon reading Notes from the House of the Dead “my heart was full of sympathy and pity for Dostoevsky, who had to endure a horrible life in prison at hard labor.” Still, Anna was not solely an admirer of his works, instead she was a quasi feminist of her generation who was eager to gain independence through her own labor. The pair had a relatively happy marriage and had four children together.

In 1868, Dostoevsky released The Idiot and in 1872, The Possessed. Both were murder novels, the first narrating a murder fueled by a senseless, rageful love and the second narrating a murder closely related to a historical murder which represents Russian terrorism of the 1800s. Finally, in 1880, Dostoevsky explored parricide in The Brothers Karamazov, his crowning literary achievement.

The dramatic tensions of the novel are rooted in a complex family seized by “Karamazovian passions.” Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov is the “wicked and sentimental” old patriarch who participated in two marriages which culminated in the birth of three sons. Dimitri Karamazav, a dark, impulsive, and sensual man, is his first son and the chief suspect for his eventual murder. Ivan, an atheist, and Alyosha, a deep reservoir of placid religious conviction, are Dimitri’s half-brothers. There is a fourth potential son, Smerdayakov, the lackey who is suspected to be Fyodor’s illegitimate son. A family fraught with hatred and internal divisions thus assumes the stage of Dostoevsky’s novel; when the murder of Fyodor unfolds in highly mysterious circumstances, the tension is lifted and the prophecy of destruction fulfilled, forcing the entire family into a period of intense moral disturbance.

The narration of Dimitri’s trial for the death of his father is the single greatest testament to Dostoevsky’s genius. The prosecutor and defense attorney’s separate speeches are true swan songs and elucidate Dostoevsky’s central goal in depicting a Russian family in its dissolution. The prosecutor poses a question: “What is this Karamazov family that has suddenly gained such notoriety all over Russia?” He then concludes that “certain basic, general elements of our modern-day educated society shone through, as it were, in the picture of this nice little family… microscopically, ‘like to the sun in a small water drop,’ yet something has been reflected, something has betrayed itself.”

Through his elegant and highly detailed descriptions of the Karamazov family, Dostoevsky encapsulates the Russian character itself. The prosecutor argues that Fyodor is a sensualist void of the instinct for spirituality but brimming with a violent zest for life; he proceeds to state that Ivan is brilliant and yet is an utter nihilist, unable to believe in anything; he remarks the Alyosha is pious and yet weak, that he has thrown himself into the embrace of the Church like a frightened child. Finally, the prosecutor concludes that by understanding these multidimensional characters, we can understand the Russian people who are “an amazing mixture of good and evil, we are lovers of enlightenment and Schiller, and at the same time we rage in taverns and tear out the beards of little drunkards, our tavern mates. Oh, we can also be good and beautiful, but only when we are feeling good and beautiful ourselves. We are, on the contrary, even possessed – precisely possessed – by the noblest ideals, but only on condition that they be attained by themselves, that they fall on our plate from the sky, and above all, gratuitously, gratuitously, so that we need pay nothing for them.”

In 1881, Dostoevsky died after suffering from an epileptic seizure. However, his inspiring impact became clear as over 40,000 mourners attended his lengthy funeral. As we read the literary masterpieces that outlive him, we are reminded of what Dostoevsky wrote to a friend after the publication of his first book: “Literature is a picture, or rather in a certain sense both a picture and a mirror.” In Dostoevsky’s works, we see ourselves on every page and attain a rich understanding of our own nature by analyzing his heavenly words.

Dostoevsky’s own life – dampened by darkness – taught him the tragic tune he weaved into his works.

Katia Anastas is an Editor in Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She loves that journalistic writing equally emphasizes creativity and truth, while allowing...