The Artist and the Muse: The Story of Alma Mahler

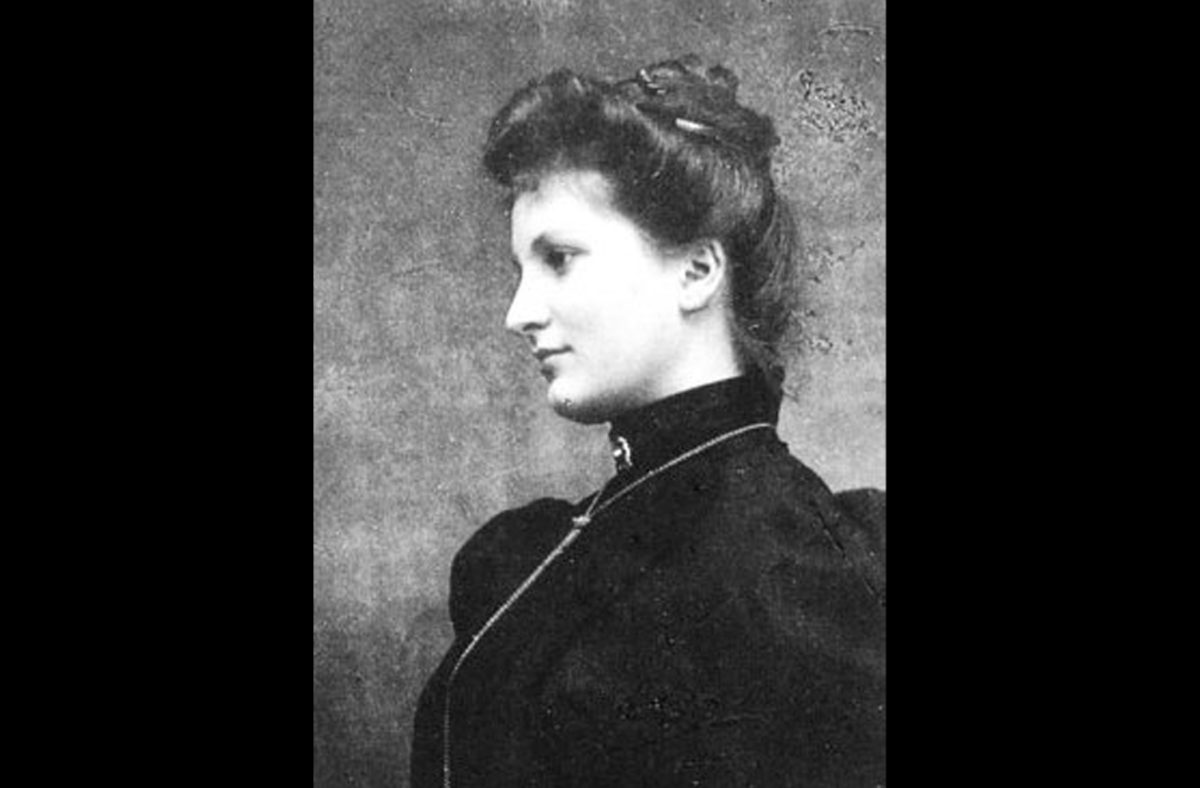

Alma Mahler, renowned as the captivating femme fatale of fin de siècle Vienna, was celebrated as a muse to the greatest creative minds, while her own exceptional artistic talents have languished in the shadows of obscurity.

The renowned Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) is well-known among classical musicians. The famous adagietto movement from his Fifth Symphony can be recognized by anyone with its masterful conviction of passion and yearning. However, few are aware that Alma Mahler, his wife to whom that piece was dedicated to, possessed her own extraordinary talent as a composer. Throughout her career, Alma Mahler composed roughly fifty works for voice and piano, only of which seventeen have endured. Unfortunately, Mahler’s social reputation was linked more closely to her romantic relationships than to her artistic talent, as she was romantically involved with multiple men, three of whom she married.

Following the death of her father, Mahler turned her attention to enhancing her musical skills, embarking on a musical education under the guidance of Josef Labor, a remarkable blind organist. Alma’s intellectual horizons were broadened by the fact that Labor, despite his own disability, not only imparted compositional knowledge to her but also opened the doors to literature. This learning path diverged from Alma’s formal education, which she abandoned at fifteen in favor of Labor’s invaluable guidance. Despite this, Alma’s pursuit of musical proficiency was hindered by her deteriorating hearing, a consequence of having smallpox as a child.

Alma’s musical mentor was Max Burckhard, the esteemed director of Vienna’s Burgtheater, the national theater of Vienna, and a trusted confidant of her late father. In addition to encouraging her musical ambitions, Burckhard indulged Alma’s love of literature by gifting her two voluminous hampers filled with books for her 17th birthday. Alma’s mother found comfort in the arms of Carl Moll, a former pupil of Schindler, and married him shortly before this momentous occasion. In 1899, Alma welcomed her beloved half-sister Maria into her life, which further changed the dynamics of her family.

Alma’s stepfather, Carl Moll, played a prominent role as one of the founding members of the Vienna Secession, an avant-garde Austrian art movement intimately connected to the birth of Art Nouveau. Alma was captivated by this group of artistic visionaries who were motivated by a desire to break free from Vienna’s conventional Imperial Academy of the Visual Arts. Alma’s association with Moll brought her into contact with a coterie of painters associated with the Succession, including the symbolist master Gustav Klimt. Klimt, renowned for his expressive and enigmatic style, fell profoundly in love with Alma and passionately declared his eternal love for her. Alma took pleasure in Klimt’s adulation, but she steadfastly refused to pursue a romantic or conjugal relationship with him. Despite this, their life-long friendship endured.

Alma’s musical odyssey began a new chapter in 1900, when, at 21, she began taking composition lessons from Alexander von Zemlinsky. The relationship between teacher and pupil transcended musical boundaries, as Zemlinsky was captivated by Alma’s allure. However, the secretive nature of their relationship resulted from Alma’s Catholic family’s disapproval of Zemlinsky’s Jewish heritage. Few confidants were aware of the extent of their affection, and Alma was advised to sever ties when strains began to appear in the relationship. In the end, compelled by these external constraints, Alma reluctantly decided to close the door on their romance. Zemlinsky poured his feelings out into his composition, The Mermaid, expressing his heartbreak and feeling of rejection.

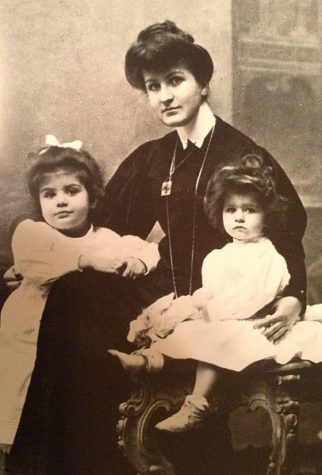

Alma’s life took an unexpected turn in November 1901, when she met the renowned Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer Gustav Mahler at a social gathering. However, their engagement remained a closely guarded secret for some time, as societal norms disapproved of Alma’s quick entry into a new romantic relationship after her breakup with Zemlinsky. They did not announce their engagement until two days before Christmas, surprising their friends and family with their commitment. Alma was subject to criticism and raised eyebrows, especially due to Mahler’s Jewish heritage and her own reputation as a provocative and capricious young woman. The couple nevertheless exchanged vows on March 9th, 1902, and their first daughter, Maria Anna, was born in November of the same year. Anna Justine, their second child, would go on to have a successful career as a sculptor, forging her own course apart from her parents’ musical heritage.

Mahler firmly believed in the traditional division of duties within a marriage, regarding himself as the composer and toiling artist, while Alma’s role was that of a loving companion and understanding partner. Mahler vehemently prohibited Alma from pursuing her own musical ambitions in accordance with this perspective. Alma reluctantly complied with her husband’s request, despite her desire to engage in the artistic endeavors dearest to her heart. However, her lack of creative outlet caused her to develop resentment, which strained the relationship between Alma and Mahler. As time passed, Alma grew to resent Mahler’s unrelenting focus on his musical career at the expense of their interpersonal marital ties and broader familial ties.

Mahler found it increasingly difficult to flourish in the opera houses of Vienna as the city’s climate grew increasingly hostile toward Jews. In 1907, the family retreated to Maiernigg in an effort to escape the intensifying anti-Semitism. As they arrived, tragedy struck when both daughters contracted scarlet fever and diphtheria. While Anna eventually recovered, Maria’s condition gradually deteriorated until her devastating death at the age of four on July 12, 1907. The tragic loss of Maria threw Alma into a deep state of mourning and cast a dark cloud over her marriage. Alma began an affair with the German architect Walter Gropius in 1910 after seeking solace and attention elsewhere.

When Mahler discovered his wife’s infidelity, he consulted the esteemed Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud, although the nature of their consultation is unclear. Some hypothesize that Mahler sought assistance in coping with his own emotional distress, while others believe he sought advice on marital matters. The 2010 film “Mahler on the Couch” proposes that Mahler’s goal was to quell Alma’s unwavering fervor for music. Regardless of the reason for the visit, the dynamics within the Mahler household shifted subtly.

In an effort to mend their fractured relationship, Mahler began to pay Alma more attention, recognizing and encouraging her musical abilities. Mahler, expressing regret for his previous dismissive attitude toward Alma’s compositions, devoted himself to researching and editing her published works. In addition, he encouraged her to compose five additional compositions, which, with his guidance, were published by the end of 1910.

Unfortunately, this newly discovered harmony in their marriage did not last long. In May 1911, Mahler passed away as a result of a severe infection that he contracted in February 1911. Alma was devastated by Mahler’s death, which marked the end of an era in her life and left her to navigate an uncertain future without her adored spouse.

Alma was involved in a turbulent relationship with the Austrian expressionist artist Oskar Kokoschka from 1912 to 1914, following the death of Gustav Mahler. What began as a passionate relationship ultimately degenerated into Kokoschka’s suffocating possessiveness. In his 1913 allegorical masterpiece “The Bride of the Wind” (Die Windsbraut), Kokoschka immortalized their tumultuous relationship by depicting himself and Alma in an intimate embrace. However, upon realizing the extent of Kokoschka’s obsession, Alma made the difficult decision to cut connections with him. Long after their separation, Kokoschka’s obsession with Alma persisted unabatedly.

During the early phases of their relationship, Kokoschka rendered Alma’s portraits with great passion, including one depicting her in the Mona Lisa pose. They were depicted in later works as a devoted couple with narratives of their shared experiences. These visual narratives were intricately woven into the fans that Kokoschka gave to Alma as sincere gifts. Kokoschka continued to create these heartfelt expressions of his affection, which he referred to as “love letters in pictorial form,” even after Alma had left his life. In 1912, Alma and Kokoschka’s arrestingly dramatic drawings alluded to the conception and subsequent loss of a child. Interpretations of these images imply that Alma may have had an abortion, causing Kokoschka to experience intense emotional anguish. Nonetheless, this event did not extinguish Kokoschka’s ardent love for Alma, which drove him to create countless portraits of her.

Kokoschka, unable to overcome his fixation, sought solace in an unorthodox endeavor. He commissioned the German dollmaker Hermine Moos to create a life-size replica of Alma. The purpose of this unusual request was to use the puppet as a stand-in for Alma in his artistic depictions. Kokoschka provided Moos with detailed instructions and multiple paintings of Alma in order to create an exact facsimile of his ex-lover. However, the outcome was far from satisfactory due to the discord between Kokoschka’s expressionist painting style and the domain of realistic doll making. Kokoschka, dissatisfied with the outcome, hesitantly incorporated the doll into his paintings.

By the end of 1918, Kokoschka proclaimed that the puppet had “completely cured” him of his obsessive desire. In honor of this self-perceived independence, he organized a champagne-filled party that conspicuously featured the doll in exquisite attire. As the night progressed into the early hours of the next morning, a drunken Kokoschka, at the crack of dawn, took the doll out to the garden and committed a macabre act by decapitating it, symbolizing the end of his turbulent love affair. Mahler reflected on her relationship with Kokoschka, later referring to it as “a battle of love,” writing, “Never before have I tasted so much hell and so much paradise.”

In the midst of her personal voyage, Alma rekindled her relationship with Walter Gropius, which culminated in their marriage on August 18th, 1915, in Berlin. In 1916, their daughter Alma Manon, affectionately known as “Mutzi,” was born. During her childhood, Manon found comfort in the care of her devoted nurse, Ida Gebauer, who accompanied her and her mother to each of their many residences. Alma, who owned three opulent properties in Vienna alone, encouraged artistic exploration and mobility. Their familial endeavors frequently led them to Weimar, Germany, where Gropius had founded the pioneering Bauhaus school of art, an institution that would profoundly influence modern design and innovation.

In 1918, a significant event occurred in Alma’s life when she gave birth prematurely to her son, Martin Carl Johannes. However, Walter Gropius soon heard rumors suggesting that the child might not be his. Alma was having an affair with the esteemed Austrian novelist Franz Werfel, unbeknownst to Gropius. Eventually, Alma acknowledged that Werfel was her child’s biological father. As anticipated, this revelation devastated Alma and Gropius’s relationship, resulting in a painful divorce.

Tragically, before legal proceedings could begin, Alma’s son succumbed to hydrocephalus, a neurological disease where spinal fluid fills cavities of the brain, passing away before he reached his first birthday. In an odd turn of events, Gropius devised a complex plan to protect Alma’s reputation. He staged a meeting with a prostitute with the intention of being caught in an act of infidelity, giving Alma grounds to apply for divorce. However, this ostensible act of compassion was merely a ploy to secure custody of Manon, and not a genuine expression of goodwill.

After their divorce was finalized in 1920, Gropius relocated to Dessau with Manon, and married Ise Frank, who became Manon’s stepmother. Alma opposed this decision vehemently and reclaimed the guardianship of her daughter, bringing her home to Vienna. Under Alma’s care, Manon had a nontraditional upbringing, freely indulging her desires. Alma, after severing ties with Gropius, cohabited openly with Franz Werfel, although they did not marry until July 6, 1929.

Alma played a pivotal role in Werfel’s rise to prominence as a novelist, dramatist, and poet during this time period through her unwavering support of his creative endeavors. While Alma encouraged Manon to pursue a musical career like her elder sister Anna, the young woman gravitated toward the performing arts, demonstrating a passion for acting. Unfortunately, Manon’s soon-to-be stepfather did not believe in her acting abilities, discouraging her ambitions.

Alma’s early years as Mrs. Mahler-Werfel were tainted by the increasing influence of the Nazi Party in Europe. Werfel, renowned for his lectures on the Ottoman Armenian Genocide, was branded a propagandist, resulting in the burning of his books by Nazis and his dismissal from the Prussian Academy of the Arts. Alma and Manon embarked on a brief sojourn to Venice in 1934, seeking refuge from the intensifying hostility. Alma was unaware that their lives were on the verge of a terrifying downward trajectory.

During their time in Venice, tragedy struck when Manon contracted polio and became paralyzed. Manon regained some mobility in her limbs upon their return to Vienna but remained gravely disabled. In an effort to cheer up her 18-year-old daughter, Alma arranged for frequent visitors and nurtured a romantic relationship between Manon and Erich Cyhlar, a young suitor. Manon stubbornly pursued an acting career despite Werfel’s objections, prompting Alma to coordinate private visits from renowned acting instructors. Manon, nearly a year after contracting polio, summoned the fortitude to perform a private concert for her mother and stepfather. Unfortunately, she succumbed to organ failure on Easter Monday, April 22nd, 1935, leaving Alma devastated.

The death of Manon marked the third catastrophe endured by Alma, who had lost three of her four children. Werfel, who had become Manon’s father figure, dedicated his 1942 novel The Song of Bernadette to her memory. In the meantime, Anna Mahler sculpted a memorial for Manon’s grave, depicting a youthful woman clutching an hourglass. However, Nazi interference prevented the installation of the sculpture. The 1950s saw the installation of a triangular monument designed by Walter Gropius as a marker for Manon’s final resting place.

Due to his Jewish ancestry, Werfel’s life continued to present obstacles, and he became increasingly vulnerable. In 1938, following the Anschluss, Alma and Werfel decided to leave Austria. With the aid of American journalist Varian Fry, they fled to the French Riviera, where they remained until 1940. Faced with renewed peril, however, Fry organized a clandestine trek across the Pyrenees on foot, which ultimately led them to Spain and Portugal. Alma and Werfel embarked on the S.S. Nea Hellas on October 4th, 1940. Nea Greece, reaching New York nine days later.

The couple eventually settled in Los Angeles and sought solace in their new environment. One of Werfel’s notable plays, “Jacobowsky and the Colonel,” was adapted into the 1958 film “Me and the Colonel.” In 1943, his novel “The Song of Bernadette” was adapted into a motion picture. In the meantime, Alma opened its doors to fellow exiles fleeing Nazi persecution, including renowned figures such as the German novelist Thomas Mann, the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, and the Austrian film director Max Reinhardt. As Werfel’s fame grew, so did their social circle. Nevertheless, before he could publish his final science fiction novel, “Star of the Unborn,” he tragically died of a heart attack, leaving Alma once again bereft.

Alma Mahler-Werfel remained a prominent member of society despite being widowed twice, garnering the title “Great Widow” from Thomas Mann. Her extravagant headwear, adorned with ostrich feather plumes, made it impossible to miss her, as they accentuated her presence. Alma adopted her new identity as an American citizen in 1946 and eventually settled in New York City, where she formed a close friendship with the renowned composer Leonard Bernstein. Bernstein held Gustav Mahler, Alma’s first spouse, in high regard for his musical contributions, prompting Alma to attend New York Philharmonic rehearsals to observe Bernstein’s masterful conducting. During her tenure in New York’s artistic circles, Alma met the famous British composer Benjamin Britten, who dedicated the Nocturne for Tenor and Small Orchestra to her.

Alma made a fleeting return to Vienna in 1947 for unresolved financial obligations. Her heart was burdened by the deaths of her mother in 1938, her sister Grete in a mental institution in 1942, and her half-sister Maria, who was affiliated with the Nazi Party, and committed suicide in 1945. Alma’s 70th birthday was a momentous occasion that elicited cordial wishes and sentiments from a multitude of former friends and acquaintances upon her return to New York’s vibrant atmosphere. The pages of her birthday book were filled with the signatures of individuals such as her ex-husband Walter Gropius, her ex-lover Oskar Kokoschka, the esteemed Thomas Mann, the talented Benjamin Britten, and the legendary Igor Stravinsky. Notably, German composer Arnold Schonberg composed a touching birthday song in his signature style, evoking the image of Alma as the gravitational force at the center of her own celestial system, surrounded by radiant satellites — an ode to her captivating and influential life, as seen through the eyes of a devoted admirer.

In the 1950s, Alma Mahler-Werfel undertook the ambitious task of writing her autobiography, entitled “And the Bridge is Love.” Relying heavily on her meticulously kept diaries, she enlisted the help of ghostwriters to convert her personal musings into a coherent literary work. The initial collaborator, Austrian author Paul Frischauer, quickly found himself at odds with Alma due to her anti-Semitic beliefs, which were instilled in her by her parents’ strong convictions. Due to this, a second ghostwriter, E. B. Ashton joined the military. Ashton, while navigating Alma’s narrative, scrupulously highlighted instances of discriminatory language and advocated for the censorship of certain ideas, especially those pertaining to living people. The publication of Alma’s autobiography elicited a spectrum of responses. Walter Gropius, her ex-husband, was offended by the portrayal of their marriage, while others were disturbed by her bigoted political views. Prior to the publication of the German version, Alma instructed the editor to remove all references to the “Jewish question” in its totality. The German edition, titled “Mein Leben” (My Life), however, failed to garner praise. Critics derided it as sensationalist and self-absorbed, pointing out Alma’s propensity to contradict herself frequently.

Alma Mahler-Werfel passed away on December 11th, 1964, at the age of 85. Her funeral was held two days later, but it wasn’t until February 8, 1965, that her body was placed to rest in the same grave as Manon’s, in Vienna’s Grinzing Cemetery. Numerous newspaper obituaries were published in response to the news of her passing, focusing primarily on her romantic relationships and citing her autobiography. In response to such an obituary, Tom Lehrer composed “Alma,” which references Mahler, Gropius, and Werfel, each of whom succumbed to Alma’s captivating influence in turn. In his obituary for Alma Mahler-Werfel, however, the Austrian author Friedrich Torberg offered an alternative viewpoint. Torberg argued that, despite the incontrovertible fact that Alma had many lovers, she was not the flirtatious and promiscuous woman the world believed her to be. They were attracted to her because she was their source of inspiration and their muse. She made personal sacrifices to assure the success of their artistic endeavors. Alma frequently felt her role was complete after her spouses and lovers attained fame, and she sought out new opportunities. Only those who acknowledged Alma’s contributions to their careers kept her friendship, as exemplified by her enduring relationship with her third spouse, Werfel.

Only fourteen of Alma Mahler’s lieder compositions have survived to the present day; their exact dates of composition are unknown, but they likely represent her earliest artistic endeavors. Despite her previous song publication, there is no evidence to imply that Alma resumed composing or engaged in discussions about potential unpublished works after the death of Gustav Mahler. She attributed her lack of creative drive to the emotional toll of living and collaborating with a neurotic and demanding intellect.

The distinctive characteristics of Alma’s musical compositions are their opulence, flirtatiousness, Wagnerian intensity, and harmonic complexity. Her compositions simultaneously emanate an intimate, sensual, endearing, and unpredictable quality. Her selection of renowned poets such as Richard Dehmel and Rainer Maria Rilke heightens the visceral and sensuous connection with nature, imbuing it with feelings ranging from suspenseful and distant to ethereal.

Richard Wagner, one of Alma’s favorite composers, infuses many of her compositions. In her song “Die stille Stadt,” she begins on the second beat of the first measure with the famous Tristan chord, employing an enharmonic spelling Wagner never used. Nonetheless, the chord’s iconic sound remains unmistakable. While each musical gesture serves the text, Alma consistently demonstrates an exquisite sensitivity to the lyricism in her works. Her allure to mysticism and contemplation of the self within is evident. She frequently selected works by her contemporaries, including Symbolist poets, and recurring themes include the interplay between gloom and light, solitude and love, and intimacy as a spiritual communion. Alma’s provocative music serves as an appropriate vehicle for the evocative imagery in these poetic expressions.

Alma’s vocal lines adhere to natural speech patterns and have declamatory qualities. The text is imbued with vitality by the interweaving of scalar progressions and substantial leaps, which, despite being vocally challenging, contribute to its vitality. The vocal line frequently gravitates toward the pitch D, prominently or not. As a song’s conclusion approaches, the vocal rarely reaches a musical resolution, leaving the piano to conclude the musical thought.

In these tracks, the piano performs a dramatic function. Alma demonstrates her mastery of the instrument by employing grand chords redolent of Brahms and Liszt. Her accompaniments are intricate, with a rapid harmonic rhythm that imparts a sense of restlessness. Textures can become dense, sometimes employing the pedal to simultaneously resonate five octaves. Major and minor chords are uncommon, giving way to the prevalence of diminished and augmented sonorities, which are frequently spelled in unconventional ways. Alma is able to traverse disparate tonalities because linear motion necessitates the use of enharmonic equivalents, which allow her to traverse vast tonalities. Her harmonies, like her writing, are audacious and ambiguous.

Regarding the formal structure, the voice and the piano exchange and develop concepts. A song’s initial section may recur at the end, providing a sense of closure to the overall form, or an ending may culminate in an unresolved harmony. Fermatas and caesuras delineate smaller sections within the compositions, whereas frequent cadence variations contribute to a greater degree of expressiveness.

Alma Mahler’s life and music demonstrate the intricate relationship between talent, ambition, and the constraints imposed by societal norms. Examining her voyage reveals a woman who both defied and yielded to the societal norms of her time. It is essential to acknowledge Alma’s undeniable impact on the artistic landscape of her era, even if her relationships and decisions are subject to critical examination. Alma Mahler, a figure of both admiration and controversy, challenges us to confront the shades of gray within the narrative of a creative life, ultimately reminding us that artistic legacies are rarely simple but rather complex tapestries that shape and redefine our understanding of music and the human spirit.

Alma Mahler, a figure of both admiration and controversy, challenges us to confront the shades of gray within the narrative of a creative life, ultimately reminding us that artistic legacies are rarely simple but rather complex tapestries that shape and redefine our understanding of music and the human spirit.

Bianca Quddus is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey’ who enjoys writing about culture and the arts. The aspect that she most loves about journalism...