Parade’s Savvy Storytelling of Antisemitism Is Not Stuck in the Past

The Broadway revival expertly comments on bigotry, not just in the South in the early 20th century, but in America today.

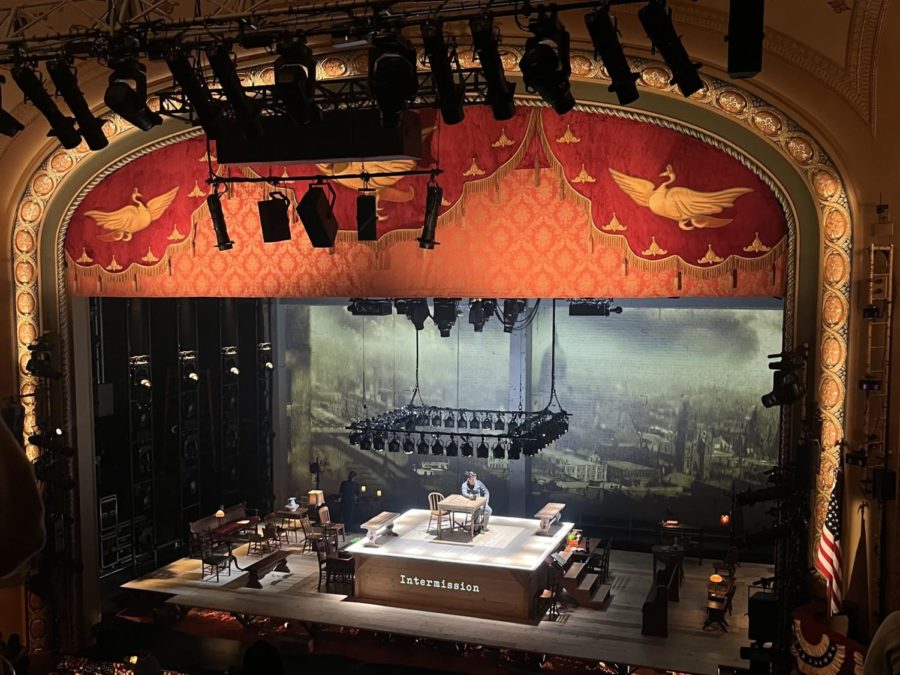

Actor Ben Platt sits on the stage of the Jacobs Theater for the entirety of the 15 minute intermission, representing the months that Leo Frank spent waiting, alone, in his jail cell.

When I first saw actors marching across the stage, waving Confederate flags and singing songs venerating the legacy of the Confederacy, I was taken aback. Though I knew that the actors were pretending and I was viewing a classic mode of storytelling, and that the ultimate goal of Parade is to critique the exact scene I was responding to, I still felt uncomfortable.

This is part of the opening act of Parade, a revival of the 1998 production about the only known lynching of a Jewish man in American history. Directed by Michael Harden, with lyrics and music by Jason Robert Brown and book by playwright Alfred Uhry, the musical takes place in Marietta, Georgia in 1913. The show stars Tony award-winning Ben Platt as Leo Frank, a Northern, educated Jewish man who operates a pencil factory in Marietta, and Micaela Diamond as Lucille Frank, his determined wife.

When 13 year-old Mary Phagan’s body is found in the basement of Frank’s pencil factory, the residents of the town along with the police department, local newspaper, and government officials, are determined to find a scapegoat, and all fingers point to the Jewish outsider from the North. As the show moved along and Frank’s trial began, I experienced what the musical does so magnificently: making the audience enablers.

Every highly choreographed, fast paced, or exciting song is given to those making up lies about Frank and trying to get him convicted, such as the malicious solicitor general Hugh Dorsey, who coaches his witnesses to provide false testimony to paint Frank as a pervert who makes a habit of assaulting girls who work in his factory. Though these numbers deal with heavy subject matter and are ultimately infuriating, they are incredibly engaging and effectively sweep up the audience in the mob mentality that became the end of Leo Frank. Platt himself rarely gets to sing a fun or captivating number unless he’s portraying the false accusations. Though Platt himself is an incredible singer and performer, he’s restricted, mirroring how Frank was restricted as the defendant who nobody believed. The effect is palpable.

There’s a brief moment in the second act when it seems as if there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. Lucille successfully gets Leo’s case reopened and the governor changes his death sentence to a life sentence, and Dorsey’s evidence is proven false; there’s hope that Frank will be pardoned. It echoes another hit musical on Broadway, Hadestown, by harping on the idea that even though we know how badly something is bound to end, every time we tell the story we can’t help but have hope that maybe this time will be different. Yet in the next scene Frank’s head is covered in a bag and he’s captured by a hateful mob, who lynches him after he calmly professes his innocence. It’s a gut-wrenching scene that demonstrates how weak rule of law was in the South at the time.

“You had some people who could exist with impunity and other people, minority groups, who were vulnerable to that impunity,” said Ms. Elizabeth MacEnulty, who teaches in the history department at Bronx Science and leads the Holocaust Leadership course, and saw the show a few months ago. “You only have a culture of lynching when people feel emboldened to do so. They know that they’re not going to have any consequences.”

The show itself is a masterful creation; it’s thought provoking and the actors’ performances are magnificent. Not only does it outwardly comment on the blatant antisemitism in the post-Civil War South, the show also artfully weaves in how black citizens who were free from slavery yet not free from subjugation, discrimination and subject to inhumane treatment, played into the social dynamic. Also in the mix, the show criticizes the South’s romanticism of the Confederacy and sensational journalism with representation of how journalists stewed up false headlines for their own profit that emboldened the mob against the Franks.

However, what’s most notable about this show is the reaction it has inspired. Parade is a revival, yet while the musical barely made an impact in 1998, with less than 100 performances before closing, this year, its impact has been huge. The show recently won the Tony awards for ‘Best Revival of a Musical’ as well as ‘Best Director,’ was nominated for four other awards, and performances are almost always sold out. “I think it’s resonating now because we’re seeing it play out,” said Ms. MacEnulty. “Sadly, now, there’s definitely such an uptick in antisemitism and intolerance in general.”

This escalation of explicit antisemitism was on display for all to see on the show’s opening night. On February 21st, 2023, members of The National Socialist Movement (a Neo-Nazi group) carried signs covered in hateful rhetoric and harassed theater-goers waiting to see the show outside the Jacobs Theatre. Their flyers and posters denounced Leo Frank’s innocence, claiming the show was spreading lies, and promoted their opposition to the Anti Defamation League, a Jewish NGO that specializes in civil rights law, which formed in response to the Leo Frank case and escalating antisemitism and bigotry.

In response to the protests, Ben Platt posted a video on Instagram, saying, “it was definitely very ugly and scary, but a wonderful reminder of why we’re telling this particular story and how special and powerful art and, particularly, theater can be.”

Micaela Diamond, Platt’s co-star, added in an interview with Playbill that the musical “is not about the Holocaust or the Jewish diaspora. It’s just about a very specific American hatred for Jews.”

This is the conversation that Parade inspires. It prompts people to reflect on the state of antisemitism not only then, but today as well. “There’s always, sadly, an undercurrent of antisemitism, but you might not see it. Just because you can’t see it doesn’t mean it’s not there,” said Ms. MacEnulty. She explained to me how in America, there have always been these “antidemocratic impulses,” such as the complete lack of rule of law that is demonstrated in Parade in the South. Sometimes those impulses are more vocalized, and sometimes they are more suppressed. During the time of Leo Frank’s lynching they were extremely vocalized, and now we’re seeing the same thing. “We’ve had moments where we’re leaning in towards democratic tendencies, and right now there’s a big push by some to turn away from that,” said Ms. MacEnulty.

The show is an important watch not just for frequent Broadway-goers or for history buffs, but for all Americans. It reminds us that those who do not know history are condemned to repeat it. Parade is not simply a retelling of the story of one man, it’s a demonstration of the divisions within American society, and how quickly democratic function can break down. Ms. MacEnulty concluded when I spoke with her, “The United States is not one thing; it’s never been one thing. We’re always fighting between these two impulses: are we an inclusive society or are we an exclusive society? What does it mean to be an American? I think that show really grappled with both of those questions beautifully.”

“We’ve had moments where we’re leaning in towards democratic tendencies and right now there’s a big push by some to turn away from that,” said Ms. Elizabeth MacEnulty, who teaches in the history department at Bronx Science and leads the Holocaust Leadership course.

Helen Stone is the Editor in Chief and Facebook Editor for 'The Science Survey.' She is interested in journalistic writing because she believes that a...