The Story Behind Gospel Music: Tales of Resilience in the Midst of Oppression

How the brutality of slavery led to the rise of gospel music.

The White House from Washington, DC, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Aretha Franklin, often referred to as the “Queen of Soul,” sings at an event honoring gospel music’s influence on American culture at the White House in 2015.

Aretha Franklin’s powerful voice cuts in as a choir echoes behind her, singing “Oh, oh, Mary” in radiant harmony. As the song crescendos, Franklin sings of biblical tales of Pharaoh and the Red Sea, of the New Testament’s Lazarus and Mary. The song, “Mary Don’t You Weep,” recorded for Franklin’s 1972 gospel album “Amazing Grace,” is known as a historic “slave song,” one that rose from the period of American slavery and portrays hidden messages of hope and resilience.

This genre of music draws from a history of oppression and violence and echoes a determination to resist and persevere. It’s a genre that coalesces rhythm and harmony, with elements of call-and-response. This is gospel music.

Today’s gospel music can be traced back to the 17th century, when the slave trade spread to North America. Many of the slaves who arrived in America came from cultures that used tonal languages, meaning that the inflection of a word mattered almost as much as its meaning. The music that they were used to was highly rhythmic, starkly contrasting more melodic Western classical music.

Gospel music originated from African American spirituals, which combined traditional African rhythms with Western music. Spirituals were a multipurpose form of folk music; they boosted morale, served as a form of communication between enslaved people, and conveyed emotions of sorrow and hope.

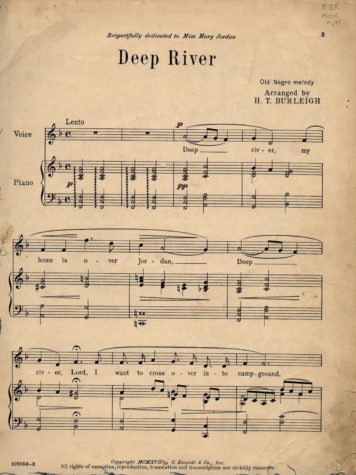

Amid gruesome plantation work, many enslaved people began singing. They sang some variations of traditional Christian hymns, but also created original compositions. These compositions were passed down orally, since most enslaved people were illiterate. Many of these songs were rooted in the Bible’s Old Testament; African American slaves related to the stories of the Israelites in captivity in Egypt and incorporated lyrics inspired by the tales of their redemption into music. Songs such as “Deep River” echo stories of The Bible in which enslaved Israelites experienced freedom. African American slaves sang these songs as stories of hope that they, too, would be delivered from the brutality of slavery.

As Charisse Barron, an assistant professor at Brown University, said, “Music was doing a lot of work for Black people. It was giving them hope. It was giving them an escape from their lives in slavery. It was helping them build community. It was helping to reinforce spiritual practices and beliefs. It was also a powerful tool that helped them send coded messages, communicate with allies and even persuade those who weren’t initially on the side of whatever cause they were fighting for.”

The call-and-response element of gospel music, which is today considered a crucial component, originated from church services for enslaved people, where preachers would call out the songs line-by-line, since they did not want the slaves to be able to read.

After the Emancipation Proclamation, formerly enslaved people brought their songs to the North during the Great Migration. The music was modified somewhat to appeal to the Northern White audience, with musicians changing the structure of harmonies to please their paying audiences.

The themes of the music also changed; no longer stuck in the back-breaking labor of slavery, gospel singers began to perform more songs that focused on Christian messages, with less content about slavery and plantation life.

In the 1930s, Black churches began to use the Hammond organ, which enhanced musicians’ abilities and again changed the structure of their music.

Gospel music played a particularly important role in the Civil Rights movement, drawing from its longstanding tradition of bringing people together. Similarly to how gospel music served to bring the community together during slavery, artists used gospel music to attract audiences and create unity, as well as to encourage the participation of adolescents in the Civil Rights movement.

Beyond the unifying aspects of the music itself, the traditional elements of gospel music shaped the Civil Rights movement, as well. Mahalia Jackson, one of the most well-known gospel artists, performed at the historic March on Washington. Martin Luther King Jr. was giving a scripted speech when Jackson, who was close to the podium, yelled, “Tell them about the dream, Martin!”

This caused him to go off-script and begin improvising in a consequential moment, creating the “I Have a Dream” speech that is so famous today. This outburst drew from the call-and-response element of gospel music, and the general Black church, where instead of preachers giving scripted sermons, they engage in more of a dialogue with the audience, and the congregation’s response shapes the sermon.

Interestingly, many famous Black singers of the twentieth century got their start singing gospel music as children at church. Aretha Franklin, born the daughter of a minister and a gospel singer in 1942, began singing in a junior gospel choir. Often referred to as the “Queen of Soul,” she became famous for her multi-octave range and powerful vocals. In 1972, she decided to make a gospel album and “return to [her] roots.” The album featured vocals that Franklin recorded when she was 14; they were recorded in her father’s church, with background vocals from the congregation.

Franklin initially resisted making the music into a studio album, feeling so strongly that “gospel is a living music, and it comes most alive during an actual service,” stressing how its power and charisma could not be captured in a studio.

After giving in and releasing the album, however, it became popular with Christians and non-Christians alike, and many credit her with the popularization of gospel music in the modern era.

Whitney Houston, also regarded as one of the best singers of the 20th century, began singing in church as a child. She later made her crossover into the pop industry, though her gospel roots remained with her; she performed at least one gospel song at almost every one of her concerts. She had always hoped to release a gospel album, though she passed away before getting the chance to, and her estate produced one after her death.

Today’s gospel music often consists of a cappella music sung by choirs. Harmony and rhythm, often integrated through the use of clapping, are important components of modern gospel music. It is common for soloists to sing the melody while the rest of the choir sings the harmony, and much of modern gospel music takes place in the traditional call-and-response format.

While some of today’s gospel music has deviated from traditional themes of perseverance and hope, many elements of gospel music from times of slavery remain. Gospel music also remains at the root of modern American musical culture, providing the basis not only for soul music but for many pop songs, as well. Regardless of musical preference, listening to gospel music serves as a reminder of resilience in the midst of large-scale oppression and a rich culture of rhythm and melody that traces back to the seventeenth century.

As Charisse Barron, an assistant professor at Brown University, said, “Music was doing a lot of work for Black people. It was giving them hope. It was giving them an escape from their lives in slavery. It was helping them build community. It was helping to reinforce spiritual practices and beliefs. It was also a powerful tool that helped them send coded messages, communicate with allies and even persuade those who weren’t initially on the side of whatever cause they were fighting for.”

Orli Strickman is an Arts and Entertainment Editor for ‘The Science Survey.’ She seeks to represent stories that do not receive a lot of mainstream...