Eve Babitz’s Revolutionary Writings

Eve Babitz, a distinguished LA writer, narrated her wild crusades through LA and defied the conventional literary establishment.

Many of Babitz’s books capture her favorite feeling of being “luxuriously involved in an unsolvable mystery.”

In 1963, Eve Babitz wrote to Joseph Heller, the author of ‘Catch-22,’ in the hopes of finding a publisher for a new novel: “Dear Joseph Heller, I am a 18-year-old blonde on Sunset Boulevard. I am also a writer.”

Ignoring the two years that had passed since her entrance into adulthood and implying that her status as a writer was only secondary to her beauty, Babitz captured her candor-laced wit and fiery quirks, proving her enduring fascination with the adventurous escapades of youth.

Ten years later, Babitz published her first book, “Eve’s Hollywood.” Its dedication – brimming with equal parts gratitude for Annie Leibovitz, Orson Welles, her orthodontist, freeways, the Chateau Marmont, sour cream, and Rainier ale – immediately highlights the fractal quality of this text composed of patchwork essays laced with humor, sharp insight, and gleeful charm.

Babitz also thanks “the Didion-Dunnes, for having to be what I’m not.” While writer Joan Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, gained popularity within established literary circles, Babitz marched to the beat of her own drum, drawing out a select group of explorative readers. Babitz did not reap the fruits of widespread fame, despite wide support from influential figures. While Joan Didion suggested that Rolling Stone publish Babitz, Steve Martin was a loyal lover and fan, and Jackie Onassis offered copies of Babitz’s works to anyone visiting L.A., Babitz did not reap the fruit of widespread fame.

Babitz’s unconventional thoughts granted her writing a seductively controversial quality. Prompted to consider marriage, she declares, “My secret ambition has always been to be a spinster,” and proving her love of the wicked she states: “I hadn’t really liked Elizabeth Taylor until she took Debbie Reynolds’ husband away from her, and then I began to love Elizabeth Taylor.”

Her agent, Erica Spellman Silverman explained to The New York Times that Babitz “was seen as… too lightweight to be serious.” Eve’s Hollywood presents Babitz’s joyride through L.A., outlining vivid snapshots of rock stars relaxing at the Chateau Marmont, of rushing into the Pacific wildly in the dead of night, and of late nights on the corner of La Brea and Sunset.

Babitz’s Hollywood crusade is emblematic of her commitment to never be dull. As a teenager, Babitz declares to her mother: “I think I’m going to be an adventuress. Is that all right?” Thus, as a “daughter of the wasteland,” she persuasively conveys the charm of her ‘humble’ hometown, capturing the beauty of a California swept by earthquakes and the Santa Ana winds and insulated by the brilliant buzz of a vibrant, luxurious life in the sun.

Babitz writes: “Culturally, L.A. has always been a humid jungle alive with seething L.A. projects that I guess people from other places just can’t see. It takes a certain kind of innocence to like L.A., anyway. It requires a certain plain happiness inside to be happy in L.A., to choose it and be happy here. When people are not happy, they fight against L.A. and say it’s a ‘wasteland’ and other helpful descriptions.”

Babitz was born in Los Angeles on May 13th, 1843. Her bohemian upbringing can be traced back to her mother, Mae Babitz, an artist and preservationist, and her father, Sol Babitz, a concert violinist and musicologist who exposed his daughter to the euphonious wonders of Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday. Igor Stravinsky, the famed Russian composer, was her godfather.

Babitz graduated a year early from Hollywood High where she developed her exemplary powers of observation. She writes that many of her classmates were “the daughters of people who were beautiful, brave, and foolhardy, who left their homes and traveled to movie dreams,” and that “people with brains went to New York and people with faces came West.”

When she turned 20, Babitz made her first major public appearance in a photograph taken by Julian Wasser. This brief modeling stint began as a stunt to irritate her married lover, Walter Hopps, who took his wife instead of Babitz to the Duchamp retrospective he led in Pasadena, California. “Anything seemed possible – for art, that night,” Babitz declared.

Over the following decade, Babitz’s adventures became L.A. legend. She designed covers for the rock album Buffalo Springfield Again along with the Byrds and Linda Ronstadt, befriended Michelle Phillips, fell in love with everyone from Harrison Ford to Jim Morrison, introduced Frank Zappa to Salvador Dalí, and sparked talk in the hottest Californian social scenes.

At 23, she also spent a year in New York where she worked for an alternative Village paper and later served as a secretary for a Madison Avenue ad salesman. Still, unaccustomed to the dreary concrete canopy of the city, she desperately missed the undying Californian sun.

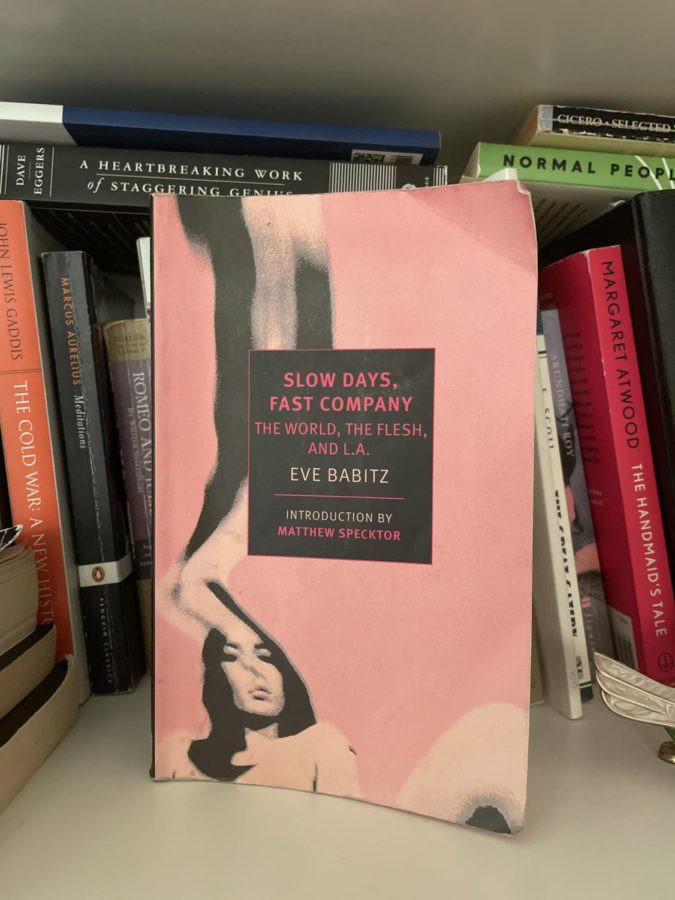

Throughout her literary career, Babitz wrote five more books and endless magazine articles. L.A. Woman (1982) featured her alter-egos, Jacaranda and Sophie, and Slow Days, Fast Company: The World, the Flesh, and L.A. (1977) beautifully evoked an image of a Southern California sun-baked and wind-swept, flooded with the sweet stench of fame and sparkling with the romantic aura of a dreamscape.

“The writing — its innocence, its sophistication, its candor, its wit, its profligacy and pluck, its willingness to fly in the face of received wisdom, its sheer headlong, impish glee — made me positively dizzy with pleasure,” Lily Anolik explained in her Vanity Fair article ‘Eve Babitz Bares It All.’

While Babitz’s agent, Spellman Silverman, called her author “F. Scott Fitzbabitz” because she was “the voice of her age,” book reviews deemed Babitz’s writing chaotic and tiresome. In her assessment of “Slow Days, Fast Company,” for The New York Times, Julia Whedon wrote: “I discern in [Babitz] the soul of a columnist, the flair of a caption writer, the sketchy intelligence of a woman [steeped in] trivia.” Moreover, P.J. O’Rourke entitled his review of “L.A. Woman” in 1982 “Not a Bad Girl but a Dull One.”

However, these critics missed Babitz’s central charm: the coupling of her wayward narrative constructions and her aphoristic observational talents. Integrating just as many references to Virginia Woolf and Henry James as parties and famous actors in Slow Days, Babitz outlines her journey from one place to the next – Emerald Bay to Bakersfield to Palm Springs – and from one romantic attachment to another. Still, it is not the dangerous details of her escapades which resonate with readers; instead, it is her sharp wit and stunning wisdom.

“The way he drove a car was the most inexplicable thing about him; he drove with an absent-minded, almost puttering kindliness, as though when he was inside a car, the world got slower; it was time for reverie almost,” Babitz observes following a baseball game with a brief fling, proving her golden, ethereal literary touch. Earlier, on a trip to the Californian vineyards, she notes, “chivalry was just another nefarious masculine scheme to keep women in their place.”

Babitz’s literary magic lies in her elusive clarity and all-encompassing element of mystery. Slow Days is sprinkled with excerpts from Babitz’s letters to an unaddressed lover. She both elucidates her innermost feelings while remaining utterly enigmatic, writing: “Virginia Woolf said that people read fiction the same way they listen to gossip, so if you’re reading this at all then you might as well read my private asides written so he’ll read it. I have to be extremely funny and wonderful around him just to get his attention at all and it’s a shame to let it all go for one person.”

In 1993, Babitz published her sixth book, “Black Swans,” an eloquent collection of essays. Laced with the bubbly buzz of her previous works, “Black Swans” records rhapsodic episodes of enchantment with the tango, violent scenes of LA burning through the rage of riots, and ghostly roamings through Hollywood Cemetery and Rodeo Gardens. Still, age-induced introspection is stitched into Babitz’s every sentence; realization follows recklessness, melancholy trails after magical madness, loss levels with love. Tinges of sadness undermine Babitz’s endless emotional high.

Babitz’s defining tragedy came around in 1997. While trying to light a cherry-flavored Tiparillo in her Volkswagen Beetle, Babitz’s acrylic skirt caught fire, scorching the majority of her body. She told the paramedics: “My friends would kill me if I died.” With no insurance, Babitz relied on these well-connected friends to auction their artwork at the Chateau Marmont to cover her expensive medical treatments.

Skin seared and mind disgruntled, the adventurous Eve Babitz ceased to exist. Laurie Pepper, Babitz’s cousin, declared: “It was the bad reviews. It was getting older. Plus, the fire. She just didn’t want to have to be ‘Eve Babitz’ anymore. Not for you or anyone else.”

Trapped in an almost posthumous state, locked in her West Hollywood apartment, and enveloped in despair and hysteria, Babitz became a hermit and a combative conservative. Converted to the right by a talk radio show, she defied her liberal lifestyle.

In 2017, she convinced an A.A. friend to log her onto Facebook and declared “I love Rush Limbaugh!” in disturbing posts. Babitz’s sister, Mirandi, soon removed the posts.

Babitz’s mental decline coincided with her renewed rise to stardom. In 2014, Lili Anolik brought Babitz back into the limelight with a Vanity Fair profile which aimed to grant the savvy Californian hedonist the same literary status as her contemporaries, Joan Didion and Pauline Kael. Anolik later published a biography: “Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of L.A.,” a true labor of love.

For months, Anolik searched for an opening with Babitz, hoping to convey her absolute reverence for her writing. “I scrawled ecstatic words on a postcard, mailed it. That didn’t work, so I hand-delivered a note… That didn’t work either… Nothing. I changed tack. Reached out to her sister, Mirandi, and cousin, Laurie…” Anolik writes. Finally, a string of Babitz’s art-loving ex-boyfriends set up a lunch date between Anolik and her literary idol.

While their first meeting was less than positive. Anolik observed that “Eve wolfed her food and wanted to leave,” this initial meal was the opening Anolik so desperately needed. Over the next few years, Anolik visited Babitz frequently, gifting her chocolate strawberries and MAGA hats as a means of eliciting stories of the good old days of crazed odysseys through LA. “That was the trick I’d discovered: grabbing her and immediately leaping backward. Execute the leap right and you’d fly over the damage that the fire and time and Huntington’s had wrought on her cerebral cortex, land cleanly in the past, untouched for whatever reason by the nuttiness,” Anolik writes in another Vanity Fair article.

After Babitz fell into relative obscurity, in 2018 New York socialites Jia Tolentino and Zosia Mamet appeared on a panel dedicated to Babitz at the New York Public Library. Then, in 2019, Kendall Jenner was photographed with a copy of “Black Swans” in her tote bag and in 2021, Audrey Hope dived into Babitz’s works in the Gossip Girl reboot.

Suddenly, Eve returned to prominence. Still, this newfound fame did not bring Babitz any joy; she muttered to her sister “it’s too late” when media requests flooded in around 2014. However, Babitz is now published in 12 countries and has increased her earnings by more than tenfold according to Ms. Spellman Silverman.

In 2019, Babitz released “I Used to Be Charming,” a collection of magazine articles. Sailing from essays splashed across the glossy pages of Vogue and Rolling Stone in the 1970s to more sober pieces produced in the sobering haze of the 1980s and 90s, Babitz reflects on a changing California and a shifting self. Discarding the distilled, unrestricted hedonistic quality of her previous works, Babitz emerges from rehab to witness the emergence of AIDS, a craze for physical fitness, and a greater commitment to clean living. Even San Francisco and Miami Beach endure inexplicable alterations, catching Babitz’s sharp eye.

Babitz even opens up to readers about her horrifying accident, recalling driving to her sister’s house in absolute shock following the flame-filled tragedy. Trapped in rehab, she told a male worker: “I used to be charming before I got here.”

The last years of Babitz’s life were worsened by Huntington’s disease, a neurodegenerative disorder that was diagnosed in the last two years of her life and yet had long afflicted her. “Chunks of her poor brain were just falling off,” Mirandi said.

At 78, Babitz passed away at U.C.L.A Medical Center in Los Angeles due to complications associated with Huntington’s. Now, her literary legacy remains, immortalizing a life full of love and loss, zest and lulls, and horror and beauty. We can always look to Babitz’s wise words: “I’m always amazed at how books find us at the time we need them, as if there’s some omniscient, benevolent librarian in the sky.”

Integrating just as many references to Virginia Woolf and Henry James as parties and famous actors in Slow Days, Babitz outlines her journey from one place to the next – Emerald Bay to Bakersfield to Palm Springs – and from one romantic attachment to another. Still, it is not the dangerous details of her escapades which resonate with readers; instead, it is her sharp wit and stunning wisdom.

Katia Anastas is an Editor in Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She loves that journalistic writing equally emphasizes creativity and truth, while allowing...