An Uncensored Look Into Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’

The Picture of Dorian Gray has been a literary sensation since its initial publication in 1890. Over 100 years later, Harvard University Press published Oscar Wilde’s manuscript and offered a new look into the classic.

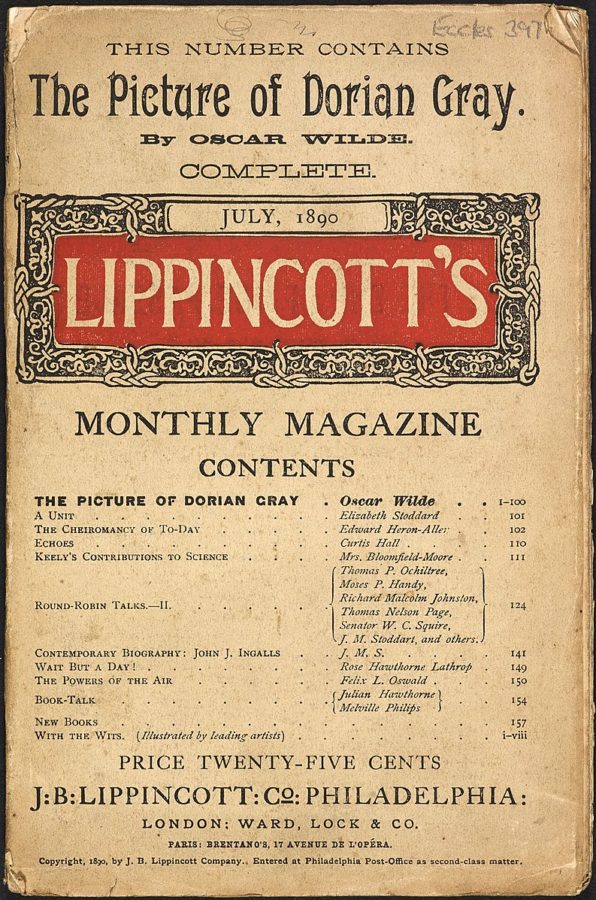

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Picture of Dorian Gray was first published as a novella in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine almost a year after it was commissioned by Stoddart. It was quickly met with outrage from Victorian audiences because of the obvious queer-coding.

On August 30th, 1899, J. M. Stoddart, editor of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, had dinner with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, T. P Gill, and most notably the infamous Oscar Wilde. He commissioned novellas from each of the writers and seven months later, he received Wilde’s manuscript for The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Upon reading it Stoddart deemed the novella to be “vulgar” and “distasteful,” prompting him to remove approximately 500 words. Despite his efforts, when the novella was published in the July 1890 edition of Lippincott’s, it was met with almost unanimous outrage. During just the first month it received 216 negative reviews. Wilde later accounted for this when expanding The Picture of Dorian Gray into a novel in which he maintained Stoddart’s edits and further subdued the content. In spite of this, public reception remained overwhelmingly unfavorable, eventually forcing Ward Lock and Company to remove the book from shelves.

Victorian readers interpreted the novel as a tale of immorality and believed that Wilde was promoting indecent behaviors – at the time, that being male homosexuality and indulgence. In an interview with me, Nicholas Frankel, Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University and editor of The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray, noted “There was a sexual paranoia in the air in his time… and I feel very strongly that was what was driving the censorship of the novel.”

A few years prior, the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 made “gross indecency” – which was defined as sexual relations between men – a punishable offense. The pre-existing conservatism of Victorian society was amplified by the 1899 Cleveland Street Scandal.

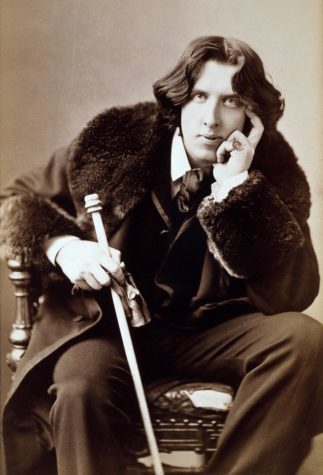

Wilde’s sexuality was made very apparent through queer-coded themes in his writing, but because of the existing social climate, it remained private. Suspicions disappeared after he married and had children with Constance Lloyd. However, in 1891, he entered a relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, an aristocrat 16 years his junior. This started the chain of events that catapulted him to controversy.

When the Marquess of Queensberry, Douglas’ father, became aware of the relationship, he was enraged. He attempted to expose Wilde by leaving a calling card at the Albemarle Club in London on February 18, 1896. This later gave Wilde the grounds to later sue for libel, though this did not work in his favor because Queensbury’s claims, although defamatory, had truth to them.

Under the Libel Act of 1843, Queensbury had to prove his allegations to avoid conviction. The defense heavily referenced The Picture of Dorian Gray, its apparent LGBTQ themes, and the negative reaction from press against Wilde, using it as evidence that he had “seduced” Lord Alfred Douglas. Wilde’s lawyer quickly withdrew the lawsuit, which many interpreted as a concession.

Afterward, Wilde was tried for 25 accounts of gross indecency (under the aforementioned Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885). During the trial The Picture of Dorian Gray remained a evidential focal point. In addition, the prosecution introduced “Two Loves,” by Alfred Douglas. In the poem he mentions “the love that dare not speak its name” – a very clear allusion to homosexuality. When asked what this phrase meant on testimony, Wilde answered “It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it… That it should be so, the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one on the pillory for it.” This pivotal moment during the first trial led to a hung jury.

The second trial occurred three weeks later than the first and it was then that Oscar Wilde was convicted. He received the maximum punishment for his crime – having to serve two years of hard labor. Following his release he was exiled to France where he spent the rest of his life. In 1900, at the young age of 46, Wilde died of meningitis in Paris. He was buried at the famous Père Lachaise Cemetery that continues to be visited today.

In a more liberal era, Oscar Wilde’s genius and bravery is finally recognized. A once ostracized figure has been reestablished as the distinguished writer that he is. Today his fans adorn his tomb with red-lipstick kisses – celebrating his legacy of breaking norms surrounding sexual morality.

In 2011, over 100 years after the initial publication, Harvard University Press published Wilde’s manuscript.

With Wilde no longer alive to approve edits, there is no way to ensure that the newly edited version of the manuscript is true to his authentic vision. But Frankel explained, “Well I’m not so concerned about being true to – absolutely faithful to his original vision as I am in drawing out the political stakes, the social stakes in editing him in a certain way. So it seems to me, historically and socially important to restore these cuts and emphasize the process of censorship.”

Although The Picture of Dorian Gray is about men and male sexuality, public concern was largely centered around women. Victorian society deemed women easily impressionable and believed that they would be corrupted by any sexual ideas, regardless of gender or preference. This can be seen in scenes where Sybil Vane was directly referred to as Dorian’s “mistress” but were reworded in the censored texts.

Basil Hallward’s “admiration” for Dorian in the manuscript is also more apparent and forward. The revised editions remove much of the romantic implication in the characterization of Basil and Dorian’s relationship. They no longer walk home “arm in arm,” they simply just walk. And instead of putting “extraordinary romance” into his portrait of Dorian Gray, he only put “some expression of all this curious artistic idolatry.”

Many of Stoddart’s edits that were unrelated to sexuality had a profound impact on characterization and theme. Oscar Wilde broke traditional grammar rules to create certain implications. Most notably, he chose to capitalize certain words, raising them to higher regard. Dorian is described by Basil as “Beautiful.” The capitalization here reflects the extent to which Basil reveres Dorian – so much so that he holds him to the same standard as God. But Sybil Vane is simply “beautiful,” there is nothing exceptional to it. She is almost disposable, easily replaced with any other woman who caters to Dorian’s vanity. Through this, Wilde is able to further emphasize the romantic undertones between Dorian and Basil while reducing his relationship with Sybil.

Capitalization in the manuscript also reflects the aesthetic influence in his writing. Wilde capitalizes words like “Diamond” and “Hydropicus.” Through grammar he transforms material objects to an almost divine status, allowing them to transcend superficial value, while also developing a further emphasis on sensation. Furthermore, Lord Henry constantly references the idea of a “new Hedonism,” with a capitalized “H” in the uncensored text, elevating the ideology to a higher regard.

Morality and its themes were another victim of censorship in The Picture of Dorian Gray. In earlier versions, Dorian appears to be more reluctant or sympathetic, showing signs of regret for his actions. In the 1891 novel, Dorian is far more consumed by sensation and only destroys the portrait to erase any evidence against him. When asked about this, Frankel said “He made changes especially to the ending to clarify – to put a certain distance between him and Dorian. He is much more judgmental of Dorian in the concluding pages in the 1891 version than in the 1890 version. In the magazine version he still leaves plenty of room for the reader to sympathize with Dorian and to believe that he genuinely wants to repent. He is writing a more traditional moral ending, where the death of Dorian Gray is his moral comeuppance.”

The way morality was presented in the novel was a reflection of Wilde’s personal experience. During his time at Oxford, Wilde was exposed to Walter Pater and in turn aestheticism. Pater’s morality was the antithesis of that of the Victorians. There was a unique emphasis on embracing ecstasy and enjoyment. Victorians, in contrast, emphasized charity, family, and self-suppression.

Wilde put much of himself into The Picture of Dorian Gray. He once said “Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry what the world thinks [of] me: Dorian what I would like to be — in other ages, perhaps.” Basil represents the reluctance Wilde feels towards wholly accepting his desires in a conservative society. In terms of Lord Henry, Frankel believes, “He does say Lord Henry is who the world sees him as – you know the dandy, the wit, the provocateur. And there’s a lot of truth to that because we know he took on that role in British Society before his arrest.” Dorian fully accepts all forms of ecstasy, sensation, committing to aestheticism and his desires. He does not fear repercussion, something Wilde was not in a position to do. Frankel notes, “Wilde says in other ages he could be Dorian Gray, because he could do it with impunity.”

The existence of three distinctive versions raises the question of which has the greatest authority in interpretation and Wilde’s legacy. Frankel believes, “The further edits he made to it before publishing it as a book need to be considered as acts of self-censorship. There is a political dimension there and a legal dimension that complicates the question of intentionality. The 1891 book version has a certain authority and is certainly a mark of Wilde’s desire to have a novel published in book form. But I don’t believe it has the same sort of intellectual authority and political authority that the uncensored version has.” No version has absolute authority – they should instead act as supplements to each other, offering different facets to the larger universe of Dorian Gray.

Beyond the question of authority lies that of interpretation, which is marked by confusion of life and art – a central theme in The Picture of Dorian Gray. The novel presents interesting moral dilemmas that mirror the conditions of Wilde’s life. But to what extent can his life be used to understand the novel?

The Picture of Dorian Gray is obviously not a biography, but in many ways, it can be looked at from that standpoint. Dorian Gray, the protagonist himself, is believed to be named after one of Wilde’s lovers John Gray, with Dorian coming from the Greek influence at Oxford (Wilde’s alma mater).

Moreover, the central characters, as Wilde famously was, are aesthetics. Basil loves art above life but can never abandon life because of his strong sense of morality. Lord Henry prioritizes art, choosing to ignore the reality of life. Dorian falls in a gray area between the two, constantly torn between aesthetics and ethics, mimicking Wilde’s own dilemma. Like Wilde, he is never able to settle this, afraid of confining to either philosophy and eventually dies as a consequence of his indecision.

The Picture of Dorian Gray has distinct, intricate layers so it is important to read with that in mind; there is no singular “correct” lens. Although there is an obvious influence from reality, that being the life of Wilde, as a piece of literature, it stands on its own. In the end, Dorian Gray and Oscar Wilde, each with their individual, but intertwined stories, are as John Ellman (Wilde’s biographer) put it, “martyr[s] of aestheticism.”

The Picture of Dorian Gray has distinct, intricate layers so it is important to read with that in mind; there is no singular “correct” lens.

Faizunnesa Mahzabin is a Copy Chief and Social Media Editor for 'The Science Survey.’ She enjoys journalistic writing because of how it can both educate...