Ghosts from the Past: Gothic Fiction of the American South

The successes and shortcomings of one of history’s most unique and fascinating literary movements.

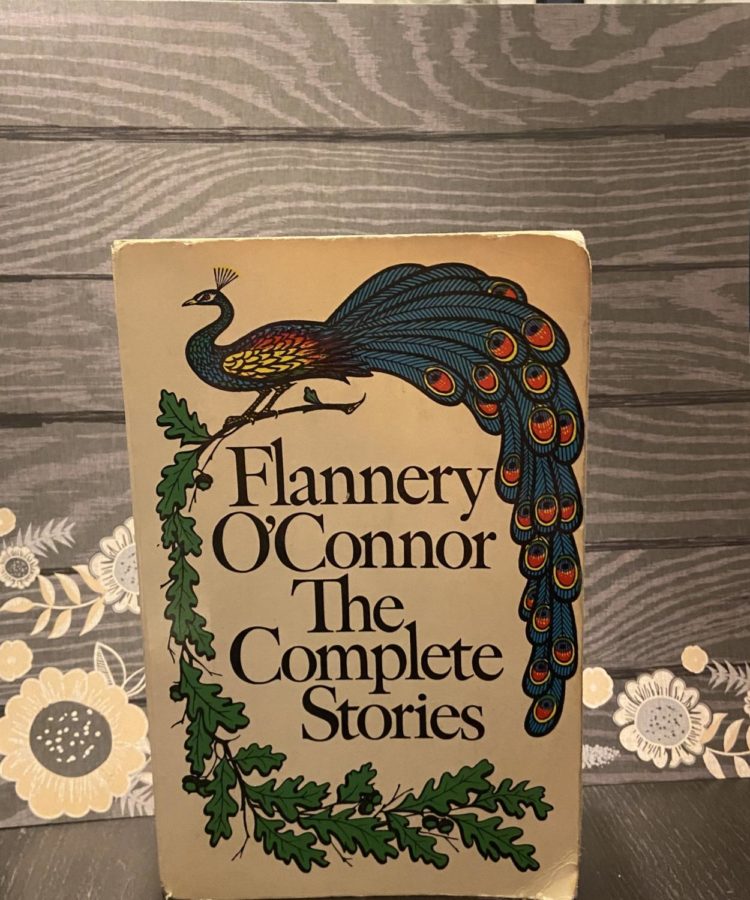

‘The Complete Stories’ by Flannery O’Connor won the National Book Award for Fiction in 1972, twelve years after O ‘Connors death, cementing her place as one of the most timeless writers to ever come out of the American South.

When Winston Churchill said “history is written by the victors,” he was clearly not talking about the American Civil War. The Confederate States didn’t just lose, they were completely decimated on every level, and yet they were the ones who have controlled the narrative in the ensuing decades. Union General Sherman marched a large host through the South toward the Atlantic Ocean, destroying everything in his path in the now famous ‘Sherman’s March to the Sea’. Besides the physical destruction the war brought to the South, the hateful ideology of the Confederacy was legally repudiated by the Emancipation Proclamation and later by the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments.

Thus began a new tradition of propagandistic Southern storytelling designed to glorify the Confederacy and craft a narrative of Southern victimhood as a way of maintaining Southern identity through Reconstruction and beyond. Southerners founded organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which claim on their website “To protect, preserve and mark the places made historic by Confederate valor.” The UDC lobbied for the creation of Confederate monuments that glorified Southern political and military leaders, and still advocates for the preservation of those symbols.

Even more insidiously, the UDC founded the Children of the Confederacy, a youth group composed of people under eighteen who are “descendants of men or women who honorably served the Confederate States of America.” The group’s stated purpose is to “honor and perpetuate the memory and deeds of high principles of the men and women of the Confederacy,” which often took the form of advocating widespread changes to how American History is taught in schools. Today, debates over how to teach about slavery and the Civil War still rage, due in no small part to efforts by groups like the UDC to rehabilitate the Confederacy in the minds of Southerners following the Civil War.

This created a new Southern culture replacing the old one, a culture that revered a past it didn’t fully understand, a culture that perpetuated victimhood while denying the truth about those victimized by the lasting impacts of slavery. By the 20th century, the Southern identity was a mess of contradictions, and the perfect petri dish in which to grow a unique literary movement: Southern Gothic.

Southern Gothic literature reflects the contradictions of Southern identity, and serious analysis of its themes and tropes can reveal a lot about how art can challenge preconceived notions about history while simultaneously being a product of them.

Southern Gothic — like all forms of Gothic fiction — is based on a fascination with the macabre, and also, importantly, with the past. Gothic novels like Frankenstein and Jane Eyre are obsessed with the past, and often feature characters who are haunted by their past choices (The Creature hunting Victor Frankenstein, or Mrs. Rochester locked in the attic, preventing Jane Eyre from marrying Mr. Rochester). But instead of vengeful monsters and insane first wives, characters in Southern Gothic fiction are haunted by the scars left behind by the Civil War.

In the short story ‘Everything that Rises Must Converge’ (1961) Southern Gothic writer Flannery O’ Connor tells the story of a young writer named Julian who lives with his racist, pro-segregation mother. One day while on the bus, the man’s mother patronizingly offers a young African American boy a penny, only to be assaulted by the boy’s mother. The event causes some sort of a psychic break in Julian’s mother, whose entire worldview is shattered.

This short story walks a fine line that is common in Southern Gothic fiction, making an effort to condemn racism while also showing sympathy for White Southerners who hold racist views. While Julian’s mother is a racist, conceited bigot, she is also presented by O’Connor as a tragic character. To O’Connor, and other Southern Gothic writers, Julian’s mother and white southerners like her are victims of a delusion forced upon them by the narrative the South adopted after the Civil War. Julian’s mother is so convinced of her own superiority and of the nobility of the South that she is unable to recover when overpowered by a black person. In this way, O’ Connor argues that she is as much a victim of her own racism as any of the African Americans she looks down on.

Obviously, there are some problems with this way of approaching the issue. By centering the experiences of white people, O’Connor frequently fails to depict the negative impacts that racism has on people of color in the South.

Take for example another O’Connor short story, ‘The Geranium’ (1946), about an old Southern man who moves to New York City with his daughter and experiences a culture shock due in no small part to the African American man who lives in the same apartment building as him. The man is horribly racist. In the story we see how this mindset leads the old man to mental anguish, but we don’t get a view of how any people of color are affected by the old man and people like him. Even the black man who lives in the old man’s apartment is less of a character and more of a plot device, used as a blank symbol of racial progress that challenges the old man’s white authority.

All of this is complicated by Flannery O’Connor’s checkered personal views on race. While it can be argued that O ‘Connor was simply a product of her time, it’s not fair to separate her from her work, which drew so much from her experience in the American South.

Another major figure in Southern Gothic fiction was Nobel Prize winning novelist William Faulkner. Faulkner’s work dealt heavily with the lives of White Southerners after the Civil War. The people in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County that features in many of Faulkner’s novels grapple with the contradictions of Southern identity, and much of Faulkner’s work candidly addresses the issue of slavery in a way that was unique for white writers at the time.

In his fiction, Faulkner seemed acutely aware of the pitfalls of the Southern mindset, succinctly describing it in his 1948 novel The Intruder in the Dust, in a passage about Pickett’s Charge, a failed Confederate offensive mounted by General Lee in 1863.

“For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is an instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out … and it’s all in the balance, it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet, it not only hasn’t begun yet, but there is still time for it not to begin.”

Once again however, the writer’s personal views muddy our view of the issues presented in their work. Faulkner famously claimed that he would fight for Mississippi against the U.S. if a war between the two ever broke out.

This problematic perspective once again illuminates the limits of the Southern Gothic genre. Southern Gothic writers are very good at illuminating the tragedy of Southern whiteness, but often falter when it comes to telling more diverse stories that explore the perspectives of different people.

Southern Gothic isn’t merely limited to literature, it also takes root in film and television. Shows like The Vampire Diaries and films like Robert Mulligan’s 1962 adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird include confederate imagery and in various ways interact with the revisionist history the South adopted after the war.

Southern Gothic authors do an extremely good job of documenting the contradictions of the White Southern experience, but the racism of many of the movement’s leading figures underscores the need for diverse stories about the American South. There is nothing inherently wrong with telling stories that center on white people, but in the case of the Civil War, it’s crucial that those stories be balanced out by narratives about the black experience. If we don’t present readers with the complete narrative, we risk letting untrue interpretations of history prevail. As William Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

This created a new Southern culture replacing the old one, a culture that revered a past it didn’t fully understand, a culture that perpetuated victimhood while denying the truth about those victimized by the lasting impacts of slavery. By the 20th century, the Southern identity was a mess of contradictions, and the perfect petri dish in which to grow a unique literary movement: Southern Gothic.

Otho Valentino Sella is an Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.' Otho has always been fascinated by stories and storytelling, and he sees journalistic...