Tales of the Future: Cyberpunk

An exploration of the genre of Cyberpunk.

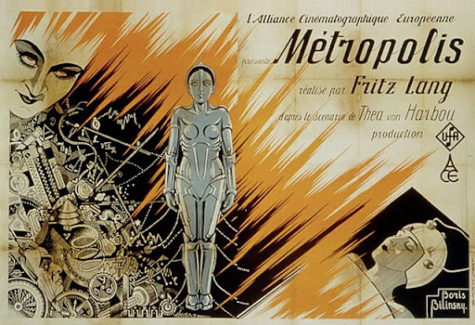

Boris Bilinski / Wikimedia Commons

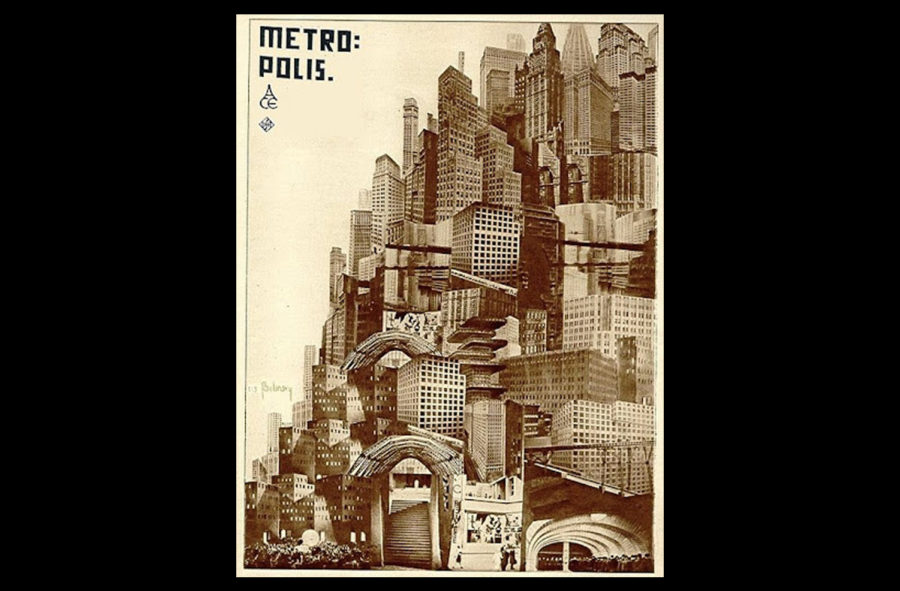

Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’ (1927) resembles Los Angeles in Ridley Scott’s ‘Blade Runner.’

The opening sequence of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner leaves the dreary, urban landscape of a dystopia Los Angeles indistinguishable from hell. The beloved city’s fall from grace is a cautionary tale to the future — the vibrant eighties synth, neon advertisements, and airborne vehicles paint a futuristic mirage that is riddled with hellish imagery and dark urban sprawl.

Despite the film’s timeless aesthetic, unique cinematography, and superb soundtrack, Blade Runner underperformed upon its release in theaters. The pessimistic themes and uncomfortable confrontations with the trajectory of our future deprived the film of the attention it deserved, but also propelled it into the hands of a few devoted fans, turning Blade Runner into a science-fiction cult classic.

The genius behind the film is Ridley Scott, a director from the coastal English town of South Shields. Scott was born into tumultuous times, just two years before the onset of World War II. He was raised in a military family with an absent father who was an officer in the British Army. In his youth, he enjoyed reading novels by the author H.G. Wells, who is often regarded as the father of science fiction. Early sci-fi films influenced Scott’s directorial style heavily and upon seeing Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the young director “knew what he wanted to do.”

Little did Scott know that he would come to revolutionize the genre of cyberpunk, an amalgamation of several different genres: film noir, expressionism, and science-fiction. These genres, combined with a high tech, low-life-city riddled with urban sprawl, set the stage for the cyberpunk world. As is the case with the archetypal cyberpunk anarchist, the genres of film noir, expressionism, and science-fiction are technologically modified to create cyberpunk.

Blade Runner took on a different name from the novel it was sculpted from; while the storyline loosely follows Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the movie’s namesake came from William Burroughs’ Blade Runner: The Film.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and Blade Runner follow a similar premise but approach it in two creatively different ways. The stark contrast between both cyberpunk pieces can be attributed to both their respective time periods and artistic medium as both Ridley Scott and Phillip K. Dick worked under circumstances that would make their art distinctively their own.

Phillip K. Dick’s novel poses a post-war scenario in which a climate related catastrophe has left Earth barren of nature. Upon the destruction of the planet, humans depart the dust covered Earth to Off-World colonies. Those deemed mentally or physically unfit live deserted in abandoned buildings on Earth, left with nothing but a desperation to live and burning curiosity of what life beyond the stars looks like. Bounty hunters such as the introspective Rick Deckard patrol the streets for man-made androids who have escaped from involuntary servitude in the Off-World colonies. When the androids are executed, or ‘retired,’ Deckard receives massive sums of money which he uses to purchase a real animal to care for. In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, owning a real life animal is a societal expectation as outlined by the religion Mercerism. But the religion that humanity is so dependent on is shattered by the hands of resistant androids — the Mercerism principles that stress the dichotomy between human empathy and android apathy is revealed as manufactured. Dick confronts questions regarding corporate authoritarianism, transhumanism, and organized religion.

From this base skeletal concept, Blade Runner came into fruition.

The successful reception of science-fiction films in the eighties, including George Lucas’ Star Wars, cultivated the growth of several niche offshoots of the genre, including cyberpunk. This leeway would give Ridley Scott the creative freedom to explore the realm of cyberpunk, or, as defined by several authors, ‘proto-cyberpunk,’ as it had not yet aesthetically developed into popular modern cyberpunk.

Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, for example, is a seminal novel of proto-cyberpunk. While the dystopian socioeconomic conditions of the novel do fall under the umbrella of cyberpunk, Dick’s visuals don’t reflect the genre.

The visuals of a cyberpunk world are tethered to the eighties — crowded streets, urban landscapes, and neon lights. The high tech, low life exists to a degree in proto-cyberpunk, but is not developed to the extent to which it is in cyberpunk. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? resembles more of a barren, deserted Earth, sparse of life and lush.

The defining visuals in Blade Runner that have come to encapsulate the genre were drawn from a comic called The Long Tomorrow. The comic was illustrated by the French artist Moebius, and tells the future-noir story of a private detective in a dense, vertical underground city with androids, boisterous bars, assassins, and flying cars. The fathers of cyberpunk — William Gibson (author of the novel Neuromancer) and Ridley Scott — derived many aesthetic inspirations from the French comics anthology Métal Hurlant, which included science-fiction and horror comics by various artists including Moebius. Métal Hurlant pioneered complex graphics, cinematic imagery, and surreal storylines which popularized cyberpunk in the eighties.

Cyberpunk first and foremost traces its origins to science-fiction. The genre seems paradoxical in the sense that science is based in fact, not fiction. However, sci-fi tends to explore tangible ideas and their consequences in a fictional world that draws parallels to our own.

One of the earliest science-fiction novels from the last two hundred years is Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, which details the adventures of Captain Nemo, his submarine, and captive men: a scientist, his servant, and a harpooner. Verne’s descriptions of Nemo’s ship, the Nautilus, is regarded as brilliantly ahead of its time as it accurately describes features of modern submarines in contrast to the primitive underwater vessels of his era.

Progressively advanced technology and the ‘rise of the machine’ prompted science-fiction to approach the question of artificial intelligence. What if the machine can think? What if the machine became human?

Questions such as these were explored in a multitude of mediums. In a silent film by Fritz Lang, Metropolis (1927), scientist Rotwang builds an android (the Maschinen-Mensch, or machine-human) to recreate a deceased woman he loved. The artificial intelligence is compromised when the city’s ruler, Fredersen, convinces the scientist to make the AI look like Maria, a woman of the lower city who agitates the working class to rise to the city above. The AI is meant to ruin Maria’s reputation among the masses, consequently smothering any opposition to the established hierarchical structure.

Elements of cyberpunk can be observed in Fritz Lang’s film, which is considered to be an example of German Expressionism.

Little did Scott know that he would come to revolutionize the genre of cyberpunk, an amalgamation of several different genres: film noir, expressionism, and science-fiction.

Karishma Ramkarran is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Observatory’ yearbook and a Staff Reporter for 'The Science Survey' newspaper. She appreciates journalistic...