Cheerleaders, Cliques, and Class Politics: A Look Into Teen Films of the 1980s

In youth cinema from the Reagan era, many popular films upheld the status quo; a few disrupted it.

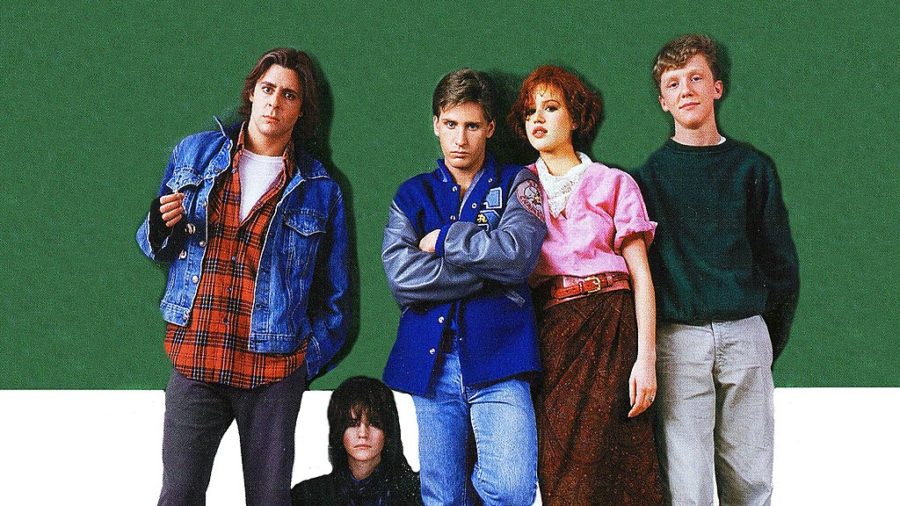

CC BY-SA 4.0

The film ‘The Breakfast Club,’ released in 1985, and written and directed by John Hughes, is one of the most iconic teen films of the 1980s.

Cheerleaders, football players, nerds, and geeks: it’s no secret that American cinema is obsessed with high school and its cliques. Though there were some notable films depicting high schoolers in prior decades, such as Grease (1978) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955), the 1980s were the decade in which the high school film cemented itself in popular culture. “The genre didn’t generate much interest in mainstream Hollywood for a while, really until 1980 or so, so for a while teen movies were the hallmark of B-studios, ” Dr. Jonathan Lewis, professor of film studies at Oregon State University, explained to me, referring to smaller, low-budget film production studios.

The high school film genre came into its own as American media was exploding in influence and popularity. The 1980s were defined by a rise in individualism, conservatism, and economic security. Following the turbulent events of the 1970s, Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, promising to instill a sense of security, hope, and familiarity in the American people. Many supporters of this new wave of conservatism used images of the “all-American” family and nostalgia for the 1950s in their embrace of traditionalism and conservative family values.

I interviewed Professor Jerry Carlson, Director of the Cinema Studies Program in the Department of Media & Communication Arts at CUNY, to learn more about the history of the high school movie in American cinema. “I find most of the teen films of the 80s to be what scholars would call ‘consensus ideology films.’” He said. “They’re not really challenging any of the larger societal structures, they’re about personal crises of students.”

By the 1980s, the American suburb was an established norm of upper-middle class life, and teen films from this era tended to focus on suburban youth and their problems. Cultural narratives of optimism and nostalgia were reflected in movies like director John Hughes’s Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club. These films were angsty yet optimistic, and their characters tended to embrace the status quo, their lives defined by upper-middle class comfort and lack of responsibility. Though characters might express frustration with the monotony of their lives or attempt to rebel against the expectations placed on them, the scope of their rebellion was limited, and did little to disrupt the status quo, often taking the form of skipping school or dating the “wrong” kind of person (that is, someone outside one’s class or social circle.) Neither characters nor films themselves tended to challenge greater power structures.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, there were huge demographic shifts in the United States. As immigration laws became less restrictive, U.S. cities diversified. However, most mainstream teen films from this era don’t reflect this, and instead focus almost exclusively on the stories of white upper-middle class suburban teenagers, often looking back to a supposedly more innocent time, as seen in films like Back to the Future and American Graffiti. “There’s an inherent nostalgia in the 80s films for the white America of the 1950s,” Professor Carlson explained.

“At one end there’s the films that are very nostalgic for a particular kind of America. At the other end of that scale, though, are the films that have a critique of consumerism and of the instrumental values of capitalism – that everything is about how much money you can accumulate and how you can rise within a particular social structure (…) A number of films satirize that aspect, the complacency of the genre.”

The 1983 film Risky Business may seem like just another complacent film chronicling the hijinks and adventures of teens attempting to escape from the rigidity of suburbia, but below the surface, it’s a dark satire of American capitalism. The fantasies of Joel Goodson (played by actor Tom Cruise) are familiar. “The dream is always the same,” he narrates, as the film opens on a hazy fantasy scene, only to abruptly switch as he finds himself in a high school classroom, where he is three hours late for his college entrance exams. With his parents gone for the weekend, Joel embarks on a series of increasingly desperate exploits. The film is dreamy and electric, with neon lights contrasting with the night time darkness and a synthy soundtrack from the electronic music band Tangerine Dream, further setting it apart from many of its cinematic peers.

As his fantasy sequence reveals, Joel finds himself stuck between hedonistic desires and stressful obligations as he lies on the cusp between youth and adulthood. In the end, he gets what he wants (mostly): his dishonest and at times illegal behavior is rewarded with an admission to Princeton University. Joel is introduced to the idea that perhaps what one sacrifices to succeed in business is not time or money but morals. Below the surface, Risky Business depicts the coming-of-age of a white upper-middle class boy and his induction into American capitalism. “In some satiric films, [high school] is the place where you can see, in its embryonic form, the birth of the monsters who will then take over the rest of society,” Professor Carlson noted.

Though director Francis Ford Coppola is most well known for the Godfather films, his two “teen films,” Rumble Fish and The Outsiders, both released in 1983 and based on novels by author S.E. Hinton, parallel each other in many ways and yet are strikingly different, especially in their cinematography. In Rumble Fish, Coppola takes a unique approach to portraying themes that many mainstream teen films of the era did not address. Like the widely popular movie The Outsiders, Rumble Fish explores what it means to be young, male, and poor in Tulsa, Oklahoma. However, while The Outsiders is a 50s Hollywood inspired classic drama about the lives of young boys in rough circumstances, Rumble Fish is strikingly artistic and experimental. Shot entirely in black and white, except for the red and blue of two fish and the lights of a police car, Coppola plays with cinematography and sound design, creating a film that is echoing, shadowy, edgy, and disjointed. “The director there is saying ‘the experience of these young people is very unusual and…one of the ways I’m going to immerse you in that is I’m going to start breathing some rules of cinema,’” Professor Carlson explained, adding that the film “draws attention to itself because it just doesn’t look and feel like a lot of other movies. Not only are the characters differently positioned in society but the movie itself looks and feels differently.”

When we look beyond the candy-colored surface of 80s teen films, it becomes clear that the era was not one of cinematic monoculture. Though many of the most popular films of the decade reflected individualistic and optimistic cultural narratives of the Reagan era, others subverted the status quo of both cinema and the world as a whole. Employing techniques such as satire, as well as unique cinematography and sound design, some filmmakers critiqued the common narratives and pitfalls of the mainstream high school genre. “All of these films are in conversation with societal values, and they have different positions on that conversation – some accepting all the values, some rejecting largely all of them,” said Professor Carlson. “I don’t think the genre can be reduced to one; it’s a spectrum of positions in conversation with society through the lens of high school experience in America.”

All of these films are in conversation with societal values, and they have different positions on that conversation – some accepting all the values, some rejecting largely all of them,” said Professor Carlson. “I don’t think the genre can be reduced to one; it’s a spectrum of positions in conversation with society through the lens of high school experience in America.”

Nora Sissenich is an Editor-In-Chief for 'The Science Survey,' a role that she values deeply because it allows her to offer guidance and insight through...