What is ‘Go Set a Watchman’?

The strange sequel to a literary classic and how it forces us to reevaluate one of America’s most beloved books.

When it comes to American literary classics, To Kill a Mockingbird has always been a paragon. Required reading in schools throughout the country, Harper Lee’s “story of a sleepy childhood town and the crisis of conscience that rocked it” is undoubtedly one of the most iconic books of the 20th century. But in the last decade, the novel has come under critical reexamination, prompted in part by the strange release of its sequel, Go Set a Watchman, in 2015.

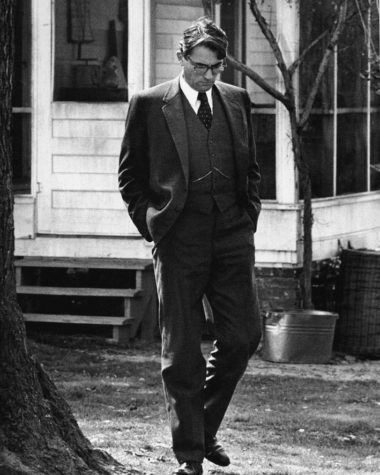

The story of To Kill a Mockingbird is common knowledge: Scout Finch reflects on her childhood in Alabama and the lessons her father Atticus taught her as he defended a Black man against a false rape accusation, following his moral compass despite the racism of his neighbors and the danger to himself. The book was published in 1960 into the arms of an America already in the throes of the Civil Rights Movement. The novel struck like lightning, becoming a commercial and critical success that won Lee the 1961 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Famously reclusive, Lee spent the next several decades as the literary equivalent of a dormant volcano, almost never appearing in public and publishing only the occasional essay.

With the release of Go Set a Watchman in 2015, however, the volcano erupted, creating a firestorm of questions surrounding the book’s characters, themes, and even the questionable circumstances of its publication.

Harper Lee wrote Go Set a Watchman in 1957 and quickly sold the manuscript to the publishing company JB Lippincott. Through Lippincott, Lee came into contact with editor Tay Hohoff, who guided Lee through the rewriting process and helped transform the draft from Watchman to Mockingbird over the course of three years. Hohoff urged Lee to focus and streamline her book, and over the next three years, Lee did just that, reworking the book entirely. To Kill a Mockingbird was published in 1960 to universal acclaim, and the manuscript of Watchman was thought to be lost. That was until a copy was found in a safe deposit box in Lee’s home in 2011, at which point the book was promptly published as a stand-alone novel, connected to Mockingbird only as a long-awaited sequel.

The book follows an adult Scout Finch (who now goes by her birth name Jean-Louise) as she returns from New York to her Alabama hometown to visit her father Atticus. Things in Maycomb county are not as Jean-Louise remembers, however, and over the course of the book she becomes disillusioned with the people and places she grew up with, especially her father, who Jean-Louise is viewing from an adult perspective for the first time.

The Atticus Finch in Go Set a Watchman is a far cry from the moral barometer of Mockingbird, and Jean-Louise is horrified to come home to a racist old man doing everything he can to halt the progress of integration in the South. Atticus introduces bigoted speakers at town council meetings, and — much to Jean-Louise’s disgust — is caught reading an anti-Civil Rights pamphlet.

Atticus Finch’s portrayal angered readers, but there were other, equally strange aspects of Watchman that raised eyebrows among fans of the original novel. Many characters and events in the book seem incongruent with how they appear in Mockingbird. Most notably, the Tom Robinson case that Atticus loses in To Kill a Mockingbird is won in Watchman, but doesn’t play nearly as central a role in the story, almost entirely reduced to a background detail from Jean Louise’s childhood.

It’s hard to explain away these apparent continuity errors, but it was quickly revealed that Go Set a Watchman was not the sequel to To Kill a Mockingbird as the marketing claimed, but was in fact an early draft that Lee revised into Mockingbird over the course of many years.

This revelation placed the strange inconsistencies into context but raised a new series of questions about the ethics of publishing Go Set a Watchman. In 2015, Harper Lee was suffering from declining health, and her sister and longtime caretaker had recently died. Harper Lee had also been uncharacteristically vocal in the past about her decision to never write another novel, so many of Lee’s family members and close friends accused the publishers of releasing the recently discovered Watchman manuscript against her wishes. This prompted an investigation by the state of Alabama, but they found no significant evidence of coercion in the publishing process. Lee died less than a year later, and the subject of Watchman’s publication is still controversial.

The other, arguably more significant impact of the turbulent release of Go Set a Watchman is the critical reexamination of To Kill a Mockingbird that closely followed its publication. Discovering that Watchman was an early draft of Mockingbird placed a spotlight on some of the elements of Mockingbird’s ideology that aren’t consistent with its image as a morally pure story about standing up for what you believe in even in the face of widespread opposition.

For one, the bigoted Atticus of Watchman is not wholly separate from his shining counterpart in Mockingbird. Though Atticus doesn’t attend Ku Klux Klan rallies in Mockingbird (as he is implied to have done in Watchman), he does spend a significant portion of the book apologizing for the actions of his overtly racist neighbors, claiming that the all-white jury who convicted Tom Robinson despite overwhelming evidence was comprised of “twelve reasonable men in everyday life.” Or the case of the racist old woman next door, who shouts racial epithets at Scout and Jem from her porch but is labeled by Atticus as “great lady” who just happened to “have her own views about things.”

This narrative parallels that of many modern opponents of police reform, who see an epidemic of racially motivated murders by police officers and argue that the fault lies with individual ‘bad apples’ rather than the system that creates and empowers them. Atticus takes this one step further in Mockingbird, defending the character of the actual people in question, claiming that their judgment is simply impaired when it comes to the topic of race.

Atticus sees racism as an issue of good people doing bad things – don’t hate the player, hate the game – and the novel itself does nothing to challenge this permissiveness. It doesn’t help that in Watchman, Jean-Louise ends up coming to a similar conclusion about the relationship between racists and anti-racists in the world.

“I guess it’s like an airplane: they’re the drag and we’re the thrust, together we make the thing fly.” This implies that too much progress toward racial equality would be just as bad as not enough, a thoroughly weird notion probably influenced by the racially tenuous situation America was in immediately following the Brown v. Board of Education decision which outlawed segregation in American schools.

Both Atticus in Mockingbird and Scout in Watchman only seem to truly challenge racism with the goal of maintaining the status quo, serving as legal defense for the wrongfully accused without challenging the society that accused them or the legal system destined to condemn them unfairly.

Many reviewers at the time criticized Watchman for its strange perspective, and for tarnishing the relationship of a classic literary hero, but many others used Watchman as a springboard to point out all the problems with Mockingbird. The subheadline to The Guardian’s review of Watchman reads: “The racism shocking readers of Harper Lee’s long-lost novel was there all along beneath the consoling fable of To Kill a Mockingbird.”

In Watchman, the perils of growing up take center stage, and Scout’s struggle with accepting the truth about her father mirrors the journey readers must now go on to reevaluate their relationship to the original book. Perhaps Harper Lee is not some literary angel who blessed us once with a potent, simple lesson, perhaps we must welcome her and her books – as Jean-Louise does to Atticus in the final pages of Watchman – “silently into the human race.”

Many reviewers at the time criticized Watchman for its strange perspective, and for tarnishing the relationship of a classic literary hero, but many others used Watchman as a springboard to point out all the problems with Mockingbird.

Otho Valentino Sella is an Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.' Otho has always been fascinated by stories and storytelling, and he sees journalistic...