To Recall the Future: A Review of ‘The Heike Story’

A review of the anime ‘The Heike Story,’ an animated adaptation of the culturally fundamental Japanese historical epic entitled ‘Heike Monogatari.’ The anime unfolds through the eyes of a young girl who has the ability to see the future but lacks the power to change the course of time.

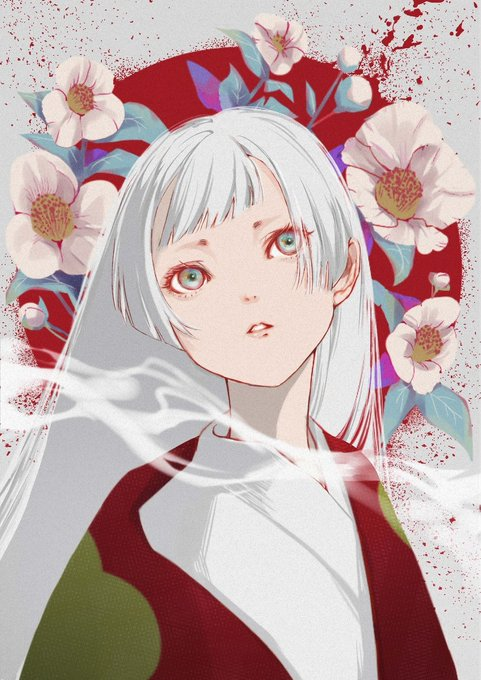

Used by permission of @Peropicnic on Twitter

Here is a digitally drawn work of fan art of an older Biwa underneath sala flowers, a motif in the “Heike Monogatari” that represents “the decline of the prosperous.”

History:

The trading of tongues, or oral storytelling, is one of the oldest forms of creative expression that has accompanied our ancestors from generation to generation — from followers of a faith meticulously singing the steps of a sacred ritual to merchants exchanging mythical tales along with their goods on the silk road.

During the Muromachi Period (the 1340s): Akashi Kakuichi, a Japanese Buddhist monk, stares at the members of the aristocracy as he recites the tale of the Heike Monogatari, accompanied by biwa-playing instrumentalists. Though Kakuichi is blind, he temporarily regains his vision as he swims through his fleeting memories to coalesce a story passed down to him by strangers on the road, creating a collage with remnants of the vibrant world he still clings onto.

Kakuichi’s version of Heike Monogatari was orally developed several times before it was written down a few months before his death. It is the most popular rendition of this historical epic following the rivalry between two royal clans — the Taira and the Minamoto — during the 12th century Genpei war in Japan. Nearly seventy decades later, the story remains unchanged, but the method of relaying it has moved from dependency on mouth and recitals to hands and animation.

Today, the prominence of oral storytelling has declined as other forms have taken their place. Newer modes of relaying stories include movies and animation, the latter of which has seen a tremendous rise in Japan since the twentieth century. Because mainstream Japanese animation, commonly known as anime, usually follows super-hero or slice-of-life stories, it is rare to come by direct adaptations of historical literature on the big screens.

One such recent example is the anime ‘The Heike Story,’ a retelling of Heike Monogatari. Produced by the animation studio Science SARU and directed by Naoko Yamada, the Japanese animated adaptation of this culturally fundamental piece of literature was released from September 16th to November 25th, 2021, on the streaming services Fuji TV and Funimation. Though it has amassed a passionate fan base, the anime is far from becoming a mainstream show, as it significantly differs from the traditional approaches.

Fatihah (@Fatiha_24), a Malaysian student artist, is an avid fan of “The Heike Story” and frequently posts fan art on her Twitter feed.

“I decided to watch it because I was interested in its premise which is not commonly found in anime,” explained Fatihah. “I’m also a fan of historical anime, so it definitely piqued my interest when it was first announced.”

Themes:

The anime’s original protagonist is a young girl named Biwa — a homage to the early storytellers and biwa players — who has one odd eye through which she can see the future.

To have the ability to see the future with your eyes means to be blind to the present, and to see time as a diaphanous stream and as a series of natural occurrences. This applies to both Biwa and the audience. Although Biwa can see the future, her efforts to change it are fruitless, leaving her frustrated at her inability to take action. Similarly, the audience can only observe and learn from the past, while they become emotionally attached to characters, knowing that their demise comes in a few episodes. Biwa’s sorrow propels itself through the screen and touches the hearts of viewers in a remarkably powerful way. The theme of accepting the past and moving on persists throughout the show.

The anime begins with the death of young Biwa’s father which leads her to the Taira clan household. The eldest son of the clan, Taira no Shigemori, also has supernatural sight and invites Biwa to live with him and his family after noting her psychic abilities. Thus, Biwa ends up right in the middle of a war and in a perfect position to observe and prophesize the lives of various important figures.

“The Jetavana Temple Bells ring the passing of all things.” This is one of the opening lines of the anime, which explains how all things, regardless of their grandeur, are bound to crumble and decay at some point. The idea of impermanence, influenced by the three marks of existence in Buddhism, emphasizes the sheer magnitude of the changing tides of history, and how we live and die at the same time. After all, how do we appreciate existence without loss? This idea is continuously drilled in with the deaths of prominent characters shown in an unceremonious and meager way.

Though Biwa merely serves as the conduit through which the audience views the story and does not directly impact the tale, she manages to leave a lasting impression on the characters around her as well as the viewers, which is a testament to Science SARU’s storytelling.

When learning about historical figures from textbooks, we usually have a hard time connecting with them; though they were once flesh and blood, we cannot engage with them on a tangible level. However, as we familiarize and identify ourselves with these figures, they start to burgeon within us.

“I feel like the anime humanizes them to the point of us feeling attached to these historical figures,” said Fatihah. “The anime made it feel as if these figures are normal human beings, like you and I, instead of larger-than-life characters. The anime highlights each of these figures having their own struggles, and I think it makes it easier for viewers to empathize and relate to them.”

The viewers spend a significant amount of time with members of the Heike clan as they grow up, starting as troublesome children mischievously running around their home and later as teenagers shivering with fear after being thrust into war. As we grow with these characters, we begin to re-contextualize our perception of people from the past.

Visuals:

The art style is one of the main differences between ‘The Heike Story’ and mainstream anime that focus more on dynamic character designs and colors. Alisha Rahman ’22, former Co-President of Bronx Science’s anime club and a third-year Japanese language student, accidentally stumbled upon the show. Watching ‘The Heike Story’ was different from her usual anime experience, especially the distinctive, illustration-type animation. She said, “It felt like the scenes were taken straight from the pictures we see in Japanese textbooks and museums, not really the colorful and flashy familiar drawing styles that we see in super popular anime.”

Fatihah agreed. “I feel like the anime is so different due to its genre and art style. The themes also felt heavier and, because it’s a retelling of a Japanese historical epic, I feel like it’s something not a lot of non-Japanese watchers are familiar with (and probably fell from a lot of anime fans’ radar because of it).”

The anime’s simplistic art style and flat colors are influenced by ukiyo-e woodblock prints, a popular medium used in the 18th century to depict many famous scenes from Heike Monogatari. The position of each clip framed on the screen supplements the author’s intent and message of the scenev— wide-screen pannings to show the larger backdrop during fights and narrow, calmer pictures to show moments of contemplation. Though the animation was drawn digitally, the presence of pen and ink seeps through with the character’s body language and the faintly colored world that is presented.

“It feels like you’re watching the past, like flipping through a complex history textbook, which adds to the melancholy sense of not being able to change anything and just accepting it as it is,” said Tanisha Khan ’22, another Bronx Science anime fan. We as the viewers only have power over ourselves to feel and interpret, and ‘The Heike Story’ allows us to dive into our emotions and practice critical thinking in a way that many mainstream anime fail to do.

Through it all, Biwa captures these pivotal moments in history through her musical performances, plucking away at her wooden lute while despondently narrating the extravagant battles and heartbreaking visions. She is the thread that sews ‘The Heike Story’ together gently and elegantly, while offering warmth even through grim scenes.

Conclusion:

Many people believe that ‘The Heike Story’ is ultimately a tragedy revolving around humans, our fallibility, and our mortality. And though Fatihah mostly agreed, she also interpreted the story more lightly.

“When I first heard of the anime’s announcement,” she recalled, “I thought to myself ‘this is definitely going to be a tragic anime’ since it’s basically a story about the downfall of a mighty clan. But after watching the trailer, I couldn’t help but feel that there’s going to be more to this story than just a tragedy. Now that I experienced the show myself, I’m happy to know that despite all the tragedy that happens throughout the show, there’s also a hopeful tone to it… just like life itself, there are always good things and bad things. Even if life is filled with misfortunes, the good things that happen should not be taken for granted and should be appreciated while we can.”

“The Heike Story” artistically and accurately encapsulates the original Heike Monogatari’s main messages while also establishing itself as a distinctive piece of media with its own unique style. It is a fantastical, almost daydream-like reminiscence of a past that seems so abstract yet palpable at the same time, offering Western audiences a peek into old Japanese literature and society. Although it is unlike any other mainstream anime, Biwa’s lute plucking will echo this story through the hearts of thousands and act as a resonance of history for a long time.

Though Biwa merely serves as the conduit through which the audience views the story and does not directly impact the tale, she manages to leave a lasting impression on the characters around her as well as the viewers, which is a testament to Science SARU’s storytelling.

Paromita Talukder is a Copy Chief for ‘The Science Survey’ where she explores topics ranging from online activism to clubs at Bronx Science. She sees...