One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’

The story and legacy of James Joyce’s magnum opus, and why it sparks such debate within the literary community.

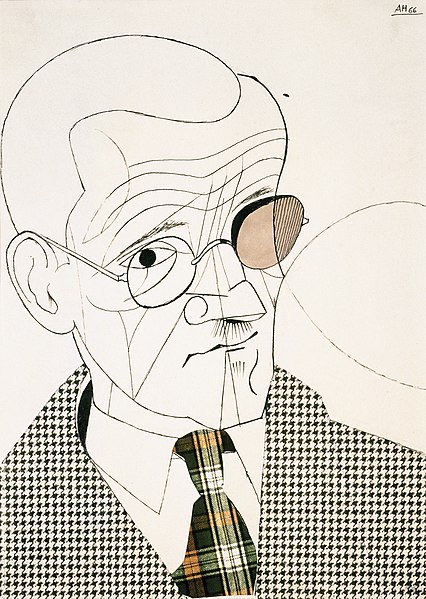

Adolf Hoffmeister, CC BY-SA 4.0

Here is an illustration of James Joyce, drawn by artist Adolf Hoffmeister.

Each June 16th, on a holiday called Bloomsday, residents of Dublin don red-ribboned boater hats or floral printed dresses and bonnets, and take to the streets, books in hand, to celebrate James Joyce’s seminal novel, Ulysses. This year marked the 100th anniversary of Joyce’s opus, which has spent that century causing all sorts of controversy within the literary community. The book is at once a fixture of English literature, frequently topping Best of All Time lists, and also seen in other quarters as an overrated mess, maligned by readers and writers alike.

“Ulysses is one of the dullest books ever written, and one of the least significant,” wrote novelist Aldous Huxley in 1925. “This is due to the total absence from the book of any sort of conflict.”

Poet T.S. Eliot disagreed, saying, “I hold this book to be the most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.”

The schism regarding Ulysses is certainly justified, as the book is famously difficult to read. As I write this I have been spending an hour a day on the book for almost a month and have yet to see the end of even the first of eighteen chapters.

The book follows three characters: the brilliant young artist Stephen Dedalus (in many ways an author-insert character), the “stately, plump” advertising canvasser Buck Mulligan, and his wife Molly. These are some of the most detailed and well-fleshed out characters in literature, and each follows such a detailed path on their day in Dublin that people can (and do) replicate it step by step. The entire novel takes place over 24 hours, creating a unique situation where over the course of reading Ulysses, the reader spends more time with the characters than they spend with themselves.

The difficulty comes from how the novel is written. Each chapter is in a different literary style, ranging from a play to a punctuation-less stream of consciousness, to a style of writing intended to imitate the repetition and meter of music. On top of all of this, Joyce has packed his book full of references so obscure and hidden that it often takes an entire second book of annotations to understand exactly what he means.

These two factors create a peculiar reading experience, where one’s eyes are constantly darting between books and computer screens to try to piece together what the characters are doing. Reading Ulysses can, at times, feel a lot like digging a hole with a spoon to find treasure that may or may not have been buried centuries ago.

I first became aware of Ulysses during the early months of the Coronavirus pandemic in the Spring of 2020, when I ran out of books and picked up an old copy of Dubliners, a short story collection by Joyce. I went through it in a few days and was mesmerized by Joyce’s charming series of vignettes, which managed to paint a lifelike picture of the city of Dublin while remaining focused on the lives of the people who inhabit it. Upon finishing Dubliners and looking into Joyce, I almost immediately discovered that he had written a much more famous novel that I had somehow never heard of. I read an excerpt from the first chapter of Ulysses, hated it, and vowed secretly to never touch the book again.

A year later, I returned to in-person schooling and received a copy of Ulysses for my birthday in January 2022, a month before its centennial. It seemed like fate. I began reading it casually later that month, only to discover that ‘reading Ulysses casually’ is impossible. So I slowly ramped up the amount of time I was spending on the book, but found that I wasn’t actually going through it faster, I was just digging deeper into the references. Feeling dejected one day, I did the math, and found that, at my current pace, it would take me a little more than four years to finish.

Thus, this is not a review of Ulysses in its entirety, but rather an attempt to understand why this strange, stubborn book has endured so long and with such youthful vigor.

Before Joyce published Ulysses as a complete work, he did what many writers of the time did and serialized it monthly in an American literary magazine called The Little Review. The novel immediately caused a stir for its controversial content, which U.S. law deemed ‘obscene’ and summarily banned. Eventually, the entire book was serialized, however, and Joyce set about finding a publisher who would put the novel into print as a complete volume.

Joyce predictably had some trouble, partly because of the book’s obscene content, but also because of his own stubbornness. Joyce was, by all accounts, a very difficult person. He dragged his family nomadically around Europe on the dime of a wealthy benefactor named Harriet Weaver, whose generosity he was constantly abusing so he could live a lavish lifestyle in whatever far-flung European city he found himself in.

His prickly side was never on greater display than when he was faced with literary criticism. He refused to change any aspect of his work (except to make it more difficult) to make it more appealing to publishers, and Ulysses was rejected by all of the major publishing houses of the time.

Eventually, Joyce found his way to a small-time English publisher based in Paris named Sylvia Beach, who operated a small bookstore called Shakespeare and Company. Beach published the novel on February 2nd, 1922, on Joyce’s 40th birthday. Beach believed in Joyce’s genius, but also seemed to find in him a friend and confidant.

She wrote of her meeting with Joyce that, “Ever conscious though I was of his genius, I knew no one so easy to talk with.” Eventually, however, they had a falling out over the rights to Ulysses, with Joyce winning out and cutting Beach out entirely.

Meanwhile, in the United States, Ulysses was put on trial and banned. It would be unbanned eleven years later in 1933 after significant efforts by the ACLU. The lawyer that led this crusade was Morris L. Ernst, who wrote after Ulysses was unbanned that “The first week of December 1933 will go down in history for two repeals, that of Prohibition and that of the legal compulsion for squeamishness in literature.”

But what exactly in Ulysses created such ‘squeamishness’? The book does include sexual references, but many of them are so deeply encoded that it would take a ridiculous amount of time to track them down. There have been a few unfortunate instances in my time with Ulysses where I trudged through Wikipedia articles and Latin translations only to find out that Joyce was just making a dirty joke.

But, those aren’t the only things hidden in the cavernous space one enters when they read between the lines of Ulysses; there are also mysteries there that are immensely satisfying to unravel. For instance, early in the book, a character says the following line to Stephen Dedalus, one of the protagonists:

“The rage of Caliban at nor seeing his face in a mirror … If Wilde were only alive to see you.” I knew Caliban was the monstrous wild-man from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, but I didn’t understand how mirrors or Oscar Wilde factored into it. It occupied space at the back of my mind for a good day before I remembered the preface to Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, in which Oscar Wilde writes, “The nineteenth century dislike of Romanticism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.”

Solving this puzzle was incredibly nourishing, and I quickly became convinced that, hidden within Ulysses, there is a puzzle for everyone that will make them feel as accomplished as I did when I figured that out.

Among the allusions and obscure references are flairs of beautiful descriptive language, which Joyce has a habit of interrupting with obscure bits of Irish slang. Take for instance, this section in the first chapter:

“Eyes, pale as the sea the wind had freshened, paler, firm and prudent. The seas’ ruler, he gazed southward over the bay, empty save for the smoke plume of the mailboat vague on the bright skyline and a sail tacking by the Muglins.” The Muglins turned out to refer to the rocky shore of Dalkey Island to the south of Dublin.

This can all be very frustrating, and Joyce certainly didn’t make it easy for readers trying to enjoy his work – rumor has it he even rewrote sections he deemed too accessible. But for Joyce, the difficulty was not just a natural byproduct of his style, it was his style.

Joyce came to see Ulysses as a stepping stone to his final major work, the novel Finnegan’s Wake, a book so strange and experimental that scholars still have not been able to fully discern its mysteries in the 83 years since its publication. Joyce characteristically stood by Finnegan’s Wake, claiming he could “justify every syllable” without ever releasing an official explanation of the text.

As for Ulysses, Joyce’s justification was clear; he saw the book as an examination of life. He claimed that “if Ulysses isn’t worth reading, then life isn’t worth living.” An honest imitation of life itself is a bold thing to claim for your novel, but if anyone can truly make this statement, it is James Joyce with his Ulysses.

Ulysses, more than any other book, serves as a reflection of the effort the reader is willing to put into it. I often found it boring, unrewarding, and needlessly complex, but when I threw myself entirely into it, I found myself enthralled by each sentence, breathlessly interrogating the words until all of Joyce’s secrets were revealed. This explains the apparent fanaticism of some of Joyce’s fans, who feel — as I sometimes do — as if Ulysses was written just for them.

As for Ulysses, Joyce’s justification was clear; he saw the book as an examination of life. He claimed that “if Ulysses isn’t worth reading, then life isn’t worth living.”

Otho Valentino Sella is an Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.' Otho has always been fascinated by stories and storytelling, and he sees journalistic...