‘Black Orpheus,’ a Tale of Passion and Loss, and Bossa Nova, Its Perfect Accompaniment

“The film’s surge of emotions, the freshness of the acting — which doesn’t look like acting at all — and the sensitivity of the direction makes it all into a wild, pagan-like poem, swirling with color and life,” said the critic John Buston, upon the film’s first release.

Desert Morocco Adventure / Unsplash

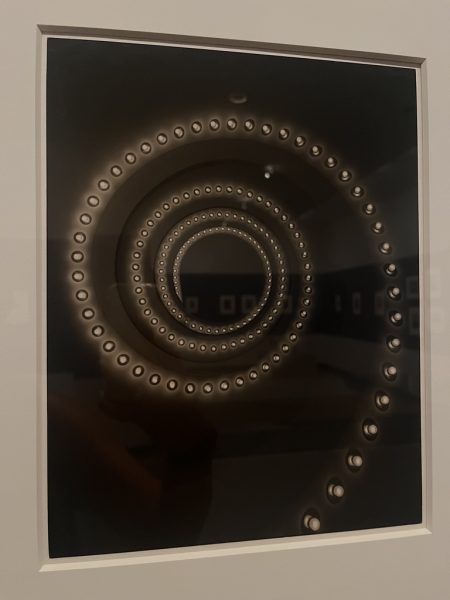

Rio de Janeiro’s landscape is one of the most beautiful natural backdrops in the world. Set against this quasi-mystical landscape, ‘Black Orpheus’ seems to take place in a fantastical dream.

A relief of the famous lovers Orpheus and Eurydice suddenly bursts into color, music, sound, and wild dancing on the streets of Rio de Janeiro at Carnival. The soft strumming of a guitar — playing the movie’s main theme, composed of nostalgic yet hopeful notes — is shattered, immediately replaced by frenzied drums, the voices of children, barking dogs, and the chatter of dancers. The sounds eventually grow louder until they overwhelm the reverie created by the guitar; soon, they die away, replaced by the beautiful voice of a lone man singing in Portuguese.

The opening track of French director Marcel Camus’ Black Orpheus (1959) masterfully captures the storyline and mood of the rest of the film, melancholic and evoking a mood of loss, both of time and of love. The soundtrack of this film, composed by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Luiz Bonfa, helps to blur the lines between what is magical and what is starkly real, creating an intoxicating blend that makes it impossible to stop watching. The viewer is in a quasi-trance, attention utterly absorbed by the bright colors of the costumes, the intense joy of the celebrations, the frenzy of activity, and the beautiful and mystical landscape that engulfs it all.

The film is entirely spoken in Portuguese, which completely immerses the viewer into the lost world of 1950s Rio during Carnival. The distinctly Brazilian songs, dancing, and festivities are entrancing and entirely unique. The soundtrack captured the public’s imagination in a way that hadn’t been seen since Anton Karas’s zither sequences for The Third Man, released a decade prior. To heighten the visual appeal of this stunning film, there are many interesting cinematographic techniques used to accentuate the electricity and exotic aspect of Carnival. Many scenes were shot with colored gels, in order to make the bright colors even more vibrant.

In Greek mythology, Orpheus and Eurydice were famous lovers whose story was cut short by the tragic death of Eurydice on their wedding day. Orpheus was a famous singer, known to be able to tame beasts with his music and song, who used his talents to bargain with Hades in order to rescue Eurydice from the underworld. Hades agreed to release Eurydice on one condition: Orpheus must have faith that she is following him out of the Underworld, and therefore he cannot look back. Orpheus breaks his promise, and Eurydice is lost forever.

There are several differences between the myth and the film. Black Orpheus complicates the original story by adding in a vengeful fiancé, Mira. Instead of being high-born, Eurydice is a simple country girl traveling to Rio to visit her cousin. Orpheus drives trams by day and sings and dances samba by night.

Though Orpheus is engaged to Mira, he and Eurydice fall in love at first sight. “Their romance develops suddenly, but their connection never felt cliche or forced,” said Ellora Klein ’22.

Despite the blossoming love story, the dark undertone of the film is revealed early on. Eurydice reveals to her cousin Serafina that she is fleeing a man who wants to kill her — a terrifying figure of a man who is Death personified. He stalks her, and, despite everyone’s efforts to keep Eurydice safe, she ends up disappearing after an encounter with Death.

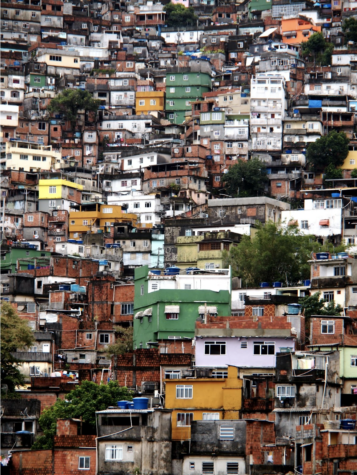

Black Orpheus subtly shows the legacy of slavery and colonialism in Brazil. Black Orpheus primarily takes place in a favela, or slum, which is extremely high up on a mountain on the periphery of the city, segregating the community from Rio. Though he is a talented samba dancer, Orpheus has to drive trams by day to support himself, and often must leave his guitar at a pawn shop in Rio when short on cash. Children run around barefoot on dirt roads and near perilous precipices. Some women give a Portuguese grocer kisses in exchange for food; others, including Serafina, skimp on food entirely as they prepare their expensive Carnival costumes. Orpheus fights Kafkaesque bureaucracy and an inefficient post-colonial government that belittles him and ignores his struggles as he attempts to find Eurydice.

Some have criticized this film, saying that it depicts poor Afro-Brazilians as frivolously dancing their cares away and as being overtly sensual. Others say that the film doesn’t really represent Afro-Brazilian culture, as it is a French production and shouldn’t be used as a method of cultural exchange. Other critics have countered that it’s a reenactment of a myth — it’s not supposed to be realistic.

Some believe that the film doesn’t go far enough in showing the struggle that Afro-Brazilians have historically faced and continue to face with poverty, segregation, and racism, making the film an entirely Western production. As the Brazilian author Ruy Castro said, “It’s hard to believe that people living in cardboard houses can be that happy.” Another issue is that French producers made much more money off the royalties of the soundtrack than composers Antonio Carlos Jobim and Luiz Bonfa. This film catapulted the two artists to fame, yet they weren’t properly compensated for their music, the feature that arguably made the film go from great to a masterpiece of cinema.

Though Black Orpheus is over sixty years old, its influence is still greatly felt in the art world. Jean-Michel Basquiat, a New York neo-expressionist artist, took inspiration from the soundtrack. Barack Obama cited Black Orpheus as being his mother’s favorite movie. Bong Joon-Ho, the director of Parasite (2019), said he felt greatly impacted by Black Orpheus after seeing it as a child. Vince Gueraldi, the composer of the Peanuts soundtrack, released an album called Jazz Impressions of Black Orpheus shortly after the film’s release. In 2013, The Buttertones released Orpheus Under the Influence, a song featuring a jazzy riff during the chorus that takes inspiration from distinctive bossa nova sounds.

Black Orpheus provides a nostalgic glimpse of the lost world of 1950s Brazilian Carnival, yet remains profoundly relevant for its themes of young love, passion, and loss. Its soundtrack, the first of its kind, continues to inspire modern artists of all mediums to create great works. Its influence is most greatly appreciated by young people aching for nostalgia.

To watch Black Orpheus on Amazon Prime (rental fee required), click HERE.

The opening track of Black Orpheus (1959) masterfully captures the storyline and mood of the rest of the film, melancholic and evoking a mood of loss, both of time and of love. The soundtrack of this film, composed by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Luiz Bonfa, helps to blur the lines between what is magical and what is starkly real, creating an intoxicating blend that makes it impossible to stop watching. The viewer is in a quasi-trance, attention utterly absorbed by the bright colors of the costumes, the intense joy of the celebrations, the frenzy of activity, and the beautiful and mystical landscape that engulfs it all.

Alexandra Smithie is an Arts and Entertainment Editor for 'The Science Survey.' She reviews and edits articles on culture and creativity for this specific...