Estranged Estates and Fallible Females: How Shirley Jackson’s ‘We Have Always Lived in the Castle’ Redefined Feminist Literature

Rejecting feminist stereotypes, Shirley Jackson encapsulated feminine strife through her eerie novels.

“Labels tend to reflect the novels/stories that the public responds to and what a writer can sell (they need to make a living, after all), despite a writer’s broad output. Jackson is not the only one who has been categorized based on mass appeal, but a deeper reading of an author’s entire output often reveals more variety than a writer’s reputation would indicate,” Mr. Licardo said.

Evergreen trees and plush, dark bushes engulf eerie mansions on crisp October evenings. Seemingly perfect families are plagued with a secret. Eccentric young women worship the occult. Many avid readers associate their favorite scenic small New England town horror novels with creatives like Stephen King, oblivious to the true trailblazer: Shirley Jackson.

The ending of a novel is perhaps the most important part of a book; it defines the author’s stylistic choices and reveals, to some extent, the purpose of the novel. Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle has one of the most influential and important endings of any horror novel:

“Poor strangers,” I said. “They have so much to be afraid of.” “Well,” Constance said, “I am afraid of spiders.” “Jonas and I will see to it that no spider ever comes near you. Oh, Constance,” I said, “we are so happy.”

How exactly does We Have Always Lived in the Castle, a novel about two sisters outcast from their community, serve as an anthropological thriller? The narrative makes a bold statement about institutional misogyny and injustice, particularly in women’s home life.

In Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, sisters Constance and Mary Katherine (Merricat) Blackwood navigate deliberate social exclusion and torment following the murder of their family. Through dry sarcasm, Jackson masterfully extends the experience of emotional and psychological exploitation to the lives of women in twentieth-century America.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle provides a realistically cynical view of domestic life, spotlighting society’s misjudgments against independent women. The protagonist, Merricat Blackwood, is emotionally stunted, retreating into her head when life becomes too real. Her incantations and OCD-like repetitions appear to result from the trauma of losing her parents, leaving Merricat permanently “stuck” — unwilling to leave her childhood but forced to face responsibilities. Her immaturity persists even as her surrounding environment and way of life becomes more threatened; in fact, Merricat regresses further with the arrival of Cousin Charles, even re-attempting to use chaos to rid the house of authority. However, this time Merricat is unsuccessful, inflicting more self-damage than external harm.

Mr. Daniel Licardo, who teaches sophomore English at Bronx Science, believes that understanding of Jackson extends beyond the traditional story arc. “What’s effective in fiction is change, movement, and thwarting of expectations (surprise), so whether progress or regression, it’s all change and movement (forward or backward) and that’s what readers like. It’s been that way since Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where people turn into flora, fauna, and natural features/phenomena. F. Scott Fitzgerald plays with the regression theme in ‘The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.’ Postmodern fiction counters all the usual writerly techniques, including movement and change, sometimes achieving a static, absurdist, comic effect, which has its own appeal to a certain readership (including me), though it’s usually never a wide one. Labels tend to reflect the novels/stories that the public responds to and what a writer can sell despite a writer’s broad output. Jackson is not the only one who has been categorized based on mass appeal, but a deeper reading of an author’s entire output often reveals more variety than a writer’s reputation would indicate,” Mr. Licardo said.

One would not expect Jackson to have grown up in sunny San Francisco; her ability to create mob-like small towns filled with gossip parallels the judgmental social groups of lavish New England society. Nevertheless, Jackson’s superficial childhood inspired many of the themes of isolation, judgment, and female unhappiness prevalent in her novels.

Jackson drew most of her inspiration from her own confined home life. Zoe Heller of The New Yorker wrote, “The motif of a lonely woman setting out to escape a miserable family or a grimly claustrophobic community and ending up ‘lost’ recurs throughout Jackson’s stories.”

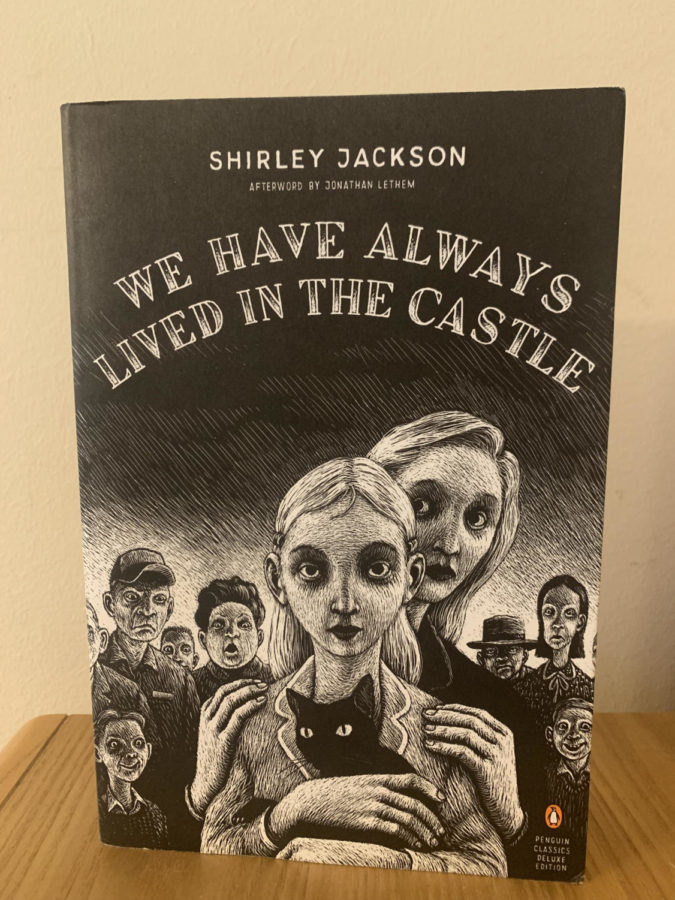

(Clay Kaufmann / Unsplash)

Jackson always viewed herself as an outsider with a strange view of the world. She, like many young women of the postwar era, was forced to grow up quickly, leaving her girlhood behind. Assuming domestic responsibilities before understanding one’s purpose and aspirations led to a generation of housewives who felt their lives had no meaning. Ali Hagget’s article, “Desperate Housewives and the Domestic Environment in Postwar Britain: Individual Perspectives” unpacks the emotional and psychological trauma that the domestic sphere left on mothers and wives. “Symptoms of anxiety and depression in women have been directly related to the stresses inherent in domestic work and other disadvantageous aspects of the female role,” Hagget wrote.

Unable to escape her husband’s suffocating presence and disapproving neighbor’s watchful eye, Jackson channeled her isolation into her work. Although We Have Always Lived in the Castle follows two sisters, their thoughts and actions act as a singular reflection of Jackson’s psychological struggle to maintain her grasp on innocence while putting forth the maturity she is expected to have. The connections Jackson created with herself and the characters make her writing unlike other works of horror — there is a certain depth in the characters that indicate the ghosts and creaky houses are only surface-level scares, compared to the macabre realities of small-town life.

Though Jackson consistently incorporates elements of horror, to consider her novels “ghost stories” would be to dismiss her anthropological commentary. “I would consider Jackson more of a northern gothic writer, as Flannery O’Connor would be a southern gothic writer. Genre labels like horror or mystery serve more of a marketing purpose for publishers and sections in a bookstore or library. Jackson belongs more in the literary fiction section, based on her work’s appearance in anthologies and school syllabi,” Licardo said.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle clearly exhibits feelings of anxiety in a myopic view that invites readers into the mind of Merricat Blackwood. The seemingly inane games metaphorically represent her desperate cling to feminine power and security. For instance, practicing witchcraft and pinning her father’s notebook as a means of banishing her “greedy” cousin Charles is indicative of Merricat’s attempts to banish the male presence or Jackson’s way of resisting her husband’s control over her social life and career. Subliminal symbolism of feminine power is implied later, with the importance of the kitchen to the plot and message of We Have Always Lived in the Castle. The domestic setting reflects the dynamic between the sisters and the expectations of women at the time, further giving insight into Jackson’s opinion on home life culture.

As Jackson struggled to conform to the ideals of domestic life, she withdrew into herself, developing agoraphobia after years of paranoia and depression. Jackson’s fears are represented in the novel, through the Blackwood mansion, a physical but also mental prison for Merricat which allows her naive habits (her witchcraft and daydreams) to foster. In some ways, Jackson reflects on her own relationship with agoraphobia: how the place she hates the most, her house, is also the place she feels safest. Jackson further alludes to her suburban San Francisco youth, entailing isolating and odd hobbies away from her family.

To define Jackson or attempt to categorize her work within one framework would be impossible; her frustration as a talented married woman, too gauche for the New England society that she was surrounded by, created an outlet of literature that related to women and other people who felt incomplete with their social and professional careers. Like Merricat, Jackson didn’t adhere to expectations; she committed her belief of being sane in an insane world through her various heroines who would memorialize her life and story.

To define Jackson or attempt to categorize her work within one framework would be impossible; her frustration as a talented married woman, too gauche for the New England society that she was surrounded by, created an outlet of literature that related to women and other people who felt incomplete with their social and professional careers.

Camila Kulahlioglu is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She hopes that her writing will inspire her peers to find new literary passions...