An Ever-Relevant Mockery of Authoritarian Power: A Review of Bulgakov’s ‘Master and Margarita’

A 1930s retelling of the Dr. Faust story in the Soviet Union, Bulgakov delivers his semi-disguised, shattering critiques of Stalin’s regime through the antics, gaslighting, and mockery carried out by Woland (Mephisto) and his devilish assistants.

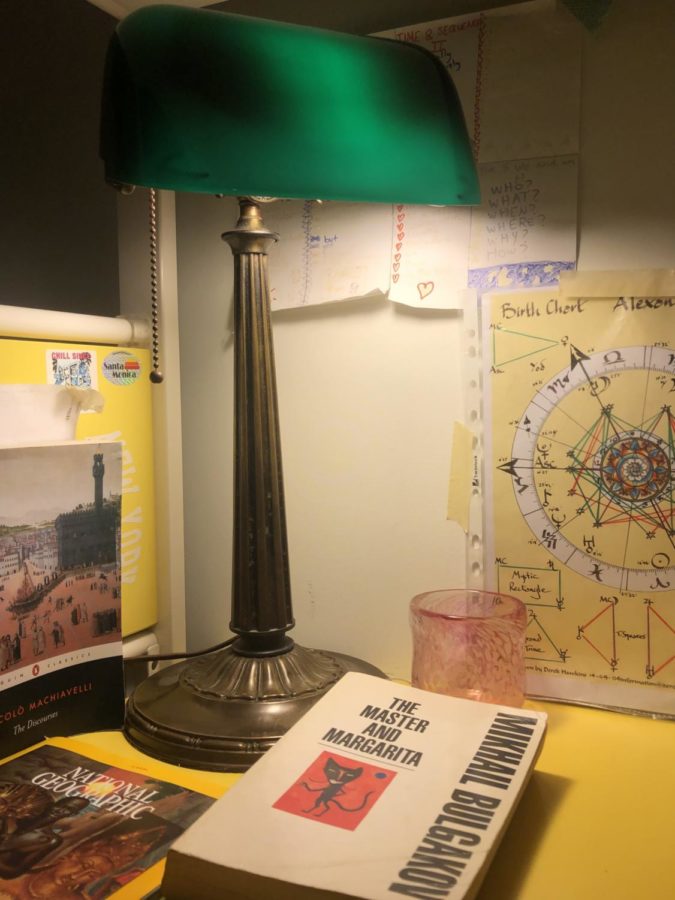

Here is my copy of ‘The Master and Margarita’ under a 1930s banker’s lamp. I like to imagine Bulgakov writing underneath a lamp such as this one. The cover art features Behemoth, the devilish talking cat.

The Master and Margarita is Mikhail Bulgakov’s masterpiece, written over the course of the tumultuous last twelve years of his life, from 1928-1940. An allegory for the USSR under the cult of personality of Stalin, Bulgakov’s work was greatly restricted. Although a samizdat version of the manuscript (meaning the work was self-published as a form of dissent) had been circulating for a while, the book was only officially published in its uncensored form in 1973.

Bulgakov masterfully retells the ancient story of Dr. Faust by combining characters from antiquity with modern figures. It intertwines a beautiful love story between a great author, the Master, and his mistress, Margarita, with the story of the devil, named Woland, arriving in Soviet Moscow. Woland disrupts ordinary life with his absurd antics carried out by his fiendish assistants. There is also a subplot: the retelling of the story of Jesus Christ through a manuscript of the Master. At its core, The Master and Margarita is deeply ironic; Christian theology is blended with supernatural elements that affect, and are sometimes embraced by, characters who claim to be atheist.

The Master and Margarita is a book that defies categorization into a single genre. “It’s almost surrealist,” said Taylor Stansfield ’22. It’s also one of the first books to feature magical realism: magic occurs in a society that claims to be rational, yet refuses to confront what’s happening in front of its very eyes.

The book begins with Woland appearing next to two atheist members (Berlioz and a poet nicknamed Homeless) of MASSOLIT, Moscow’s elite institute for artists. Ironically, MASSOLIT is a Russian abbreviation for “literature for the masses.” Woland engages them in discussions about theology, specifically through referencing the Master’s text about the story of Yeshua Ha-Nozri, or Jesus Christ, and Pontius Pilate. He terribly frightens the poet, Homeless, by making bizarre predictions about Berlioz’s gruesome death. Though Berlioz, the head of MASSOLIT, dismisses these prophecies as insane ravings, they end up coming true within a few pages. Woland’s assistants — a giant talking cat (Behemoth), a beautiful vampire (Hella), a hitman with a single fang (Azazello), and a grotesque valet (Koroviev) — wreak havoc on the city. The artists and writers of MASSOLIT, members of high society, are swept up in the chaos that this devilish entourage creates in a series of black magic, tricks, embarrassment, and gruesome murders, and many are brought to shame. Meanwhile, the Master, a Christ-like figure, languishes in a mental hospital as his lover, Margarita, makes a pact with Woland in order to save the Master’s manuscript.

Though all these time jumps, historical references, and parallel plots might be intimidating, the reader quickly becomes accustomed to the way the story is told. “I wasn’t expecting how much it would jump around and how little you could plan for what was going to happen. I think that the nonlinearity of the story keeps the reader’s interest,” said Stansfield.

The Master and Margarita is a story about the author himself. The famous quote, “Manuscripts don’t burn!”, which Woland says to the Master as he helps the Master recover and tell his story about Ha-Nozri, is a direct reference to Bulgakov burning the first version of the book in order to avoid a crackdown from Stalin.

Despite imprisoning and assassinating many prominent artists, writers, and critics, Stalin took a somewhat positive interest in Bulgakov. This was a unique relationship, especially as Bulgakov was an author who considered himself a Russian rather than a Soviet. Despite Bulgakov’s shattering criticisms of the regime, Stalin allowed Bulgakov to pursue his theatrical career, though he was forced to abandon his literary passion.

At its heart, The Master and Margarita is a satirical, quasi-biblical allegory that represents themes that are crucial to the human experience, such as struggle between good and evil, corruption in government and high society, human fragility, religion and prophecy, and the endurance of love over all. Most of all, it’s intriguing, entertaining, and comical.

There has never been a more relevant time to read The Master and Margarita. With war in Europe raging as Russia invades Ukraine, it’s easy to feel despair at the seemingly inevitable rise of totalitarianism. The Master and Margarita inspires hope, as it ridicules the very nature of autocratic power. Despite living under an oppressive regime, Bulgakov was able to laugh at the absurdities of Stalin and make a mockery of the USSR. He was fearless, even though he knew how harshly the regime cracked down on artists who expressed dissent.

In a time of rampant disinformation, fake news, and propaganda, Bulgakov’s novel represents what it means to be truthful and creative in the looming shadow of authoritarianism.

“Anything can happen, so it keeps you on your toes,” said Stansfield. “It’s unlike any book I’ve ever read.”

At its heart, The Master and Margarita is a satirical, quasi-biblical allegory that represents themes that are crucial to the human experience, such as struggle between good and evil, corruption in government and high society, human fragility, religion and prophecy, and the endurance of love over all.

Alexandra Smithie is an Arts and Entertainment Editor for 'The Science Survey.' She reviews and edits articles on culture and creativity for this specific...