Vampires: A Fangtastic History

How storytellers throughout history have invented and reinvented Halloween’s most iconic monster.

Edvard Munch, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Pictured is the painting ‘Vampire’ by Edvard Munch, painted in 1895.

A caped figure casts a long shadow on a cold castle wall, his silk robes dripping with blood. He passes through the eerie cobwebbed halls, accompanied only by sourceless organ music that sends sonorous chords ringing through the ornate foyer and into the dismal Transylvanian night.

The image of an Eastern European castle inhabited by reclusive, blood-craving noblemen is associated with most vampires, but it is practically synonymous with one name in particular; Dracula. The archetypal work of vampire fiction, Dracula, was written in 1897 by Bram Stoker and pioneered many of the tropes that still define many vampire stories to this day. Within the last century, however, vampire stories have strayed from the well-established gothic formulas, as authors and filmmakers have adapted the monsters to incorporate more modern elements.

While this may seem to some like too much of a departure from the themes of Stoker’s novel, it is important to remember that Dracula was far from the first vampire story. Stoker based his novel on centuries of folklore and myth, and changing up his formula is not so much breaking tradition as continuing it.

Folklore – Prehistory – 1896

Vampires have existed in folklore for centuries, and though it is impossible to pinpoint their first appearance, there are clear continuities between the superstitions of the past and the vampire stories that followed.

There are records of blood-sucking monsters appearing in texts as far back as Ancient Mesopotamia, and almost all ancient cultures have some folk legend that can be considered precursors to vampires, but the major traditional folk stories that influenced Bram Stoker came from Eastern Europe.

In European folklore, the dead rising as evil monsters was a sincere concern, and the Serbian word Vampir was used throughout the continent as a general term used to describe the undead.

Precisely how the dead came to life varied from country to country, but some generally accepted tactics would ensure that your dead loved ones would not come back to haunt you. Burying your dead with garlic or with a stake in their heart were surefire ways to stop them from rising as vampires, and Bram Stoker repurposed both methods as weaknesses for Count Dracula. These folk beliefs followed Europeans into their colonization of North America, leading to the New England Vampire Panic of the 1800s, a witch-hunt-esque event in which people killed one another under suspicion of being vampires.

Cases of tuberculosis caused dead bodies to bloat and their mouths to ooze blood, leading New Englanders to think that vampires lived among them, feasting on the corpses of the dead. At least six people were accused of vampirism and killed during the New England Vampire Panic. The last recorded victim was Mercy Lena Brown, a nineteen-year-old.

The vampire stories that were told before Dracula vary wildly, but they all reflect genuine fears that gripped people in Europe and New England, fears of death, disease, and a world of supernatural danger that lurked just below the surface of daily life.

Dracula and the Victorian Vampire – 1897 – 1970

In 1897, when Bram Stoker first published Dracula, it was far from a financial success. However, shortly after Stoker’s death, the novel rose again through its many adaptations, popularizing the now-iconic image of the Victorian Vampire. Stoker’s novel revolutionized vampires by synthesizing various folk stories into a set of recognizable “rules” that vampires in his universe had to follow. Dracula cannot enter a house uninvited, burns in direct sunlight, and has an overwhelming hunger for human blood. These qualities still define what makes a monster a vampire, and changing up the rules slightly is a popular way for authors to make the vampires in their stories unique.

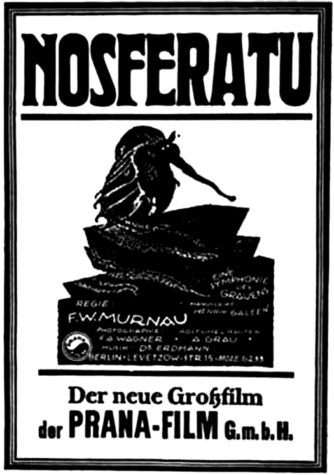

Accompanying the mainstreaming of the novel, the first-ever vampire movie, Nosferatu was released by German director F.W. Murnau in 1922. The movie was an unlicensed adaptation (meaning it was made without the permission of Stoker or his heirs), and as a result, many of the names and locations are changed. Dracula becomes the fiendish Count Orlok (played by Max Schreck), and London is replaced with the German city of Bremen. Eventually, Stoker’s heirs sued the filmmakers, and as part of the settlement, many of the original copies of the film were destroyed.

A few prints survived, and today Nosferatu is considered one of the greatest masterpieces of silent film.

In 1931, Bela Lugosi starred in an official film adaptation of the novel after playing the role on Broadway. This movie has been somewhat lost in the sea of subsequent Dracula films, but it remains to many scholars the ultimate representation of the themes presented in the novel, spearheaded by Lugosi’s campy, regal, and fun portrayal of the titular Count.

Dracula and its popular film adaptations also codified many of the themes that people now associate with vampires. The count himself represents the dangers associated with desire, and as a result, is given a stylish allure that still graces vampires to this day. In the novel, Dracula embodies desire, manipulating the protagonist’s wife with his cold, seductive charm, and very nearly turning her into a vampire. One of the major messages of the novel is that traditional gender roles that Victorian Europe had established were there for a reason, and subverting them would ultimately lead to depravity.

When adapting these themes into film, filmmakers needed to create a Dracula who was charming enough that he would be a believable source of temptation. To achieve this effect, they placed heavy emphasis on the aesthetics of the count and his environment – dark capes, slicked-back hair, and gothic architecture have all since become synonymous with vampires.

The Modern Vampire 1971 – Present

As successful as Dracula’s archetypal Victorian Vampire was, as times began to change, Stoker’s rigid themes about the dangers of desire waned in relevance. But rather than abandon vampires altogether, writers decided to turn the camera around, creating a new type of vampire fiction that painted these immortal, bloodsucking creatures in a more sympathetic light.

In 1976, Anne Rice published Interview With the Vampire, the story of an American vampire named Louis looking back on his immortal life and its various ups and downs. This book and its eleven sequels (known collectively as The Vampire Chronicles) are some of the first mainstream works of vampire fiction to present the world from the point of view of vampires, introducing them as victims of a curse, and not the gleeful stand-ins for sin that Dracula and his contemporaries were. Interview With the Vampire also expanded upon many of Stoker’s less obvious themes regarding desire, implying heavily that many of its male characters experienced homosexual attraction, something that Stoker (who may have been a homosexual himself) alluded to in his novel.

The trend of subverting classic vampire tropes continued into the 21st century with properties like Twilight and The Vampire Diaries, which brought vampires into modern-day settings and made them interact with people other than European maidens and brooding German vampire hunters. These books and movies also changed up many of the established vampire “rules.” Twilight vampires famously sparkle in sunlight instead of burning, and vampires from TVD can see their reflection in the mirror, something that Dracula himself was unable to do.

But whether vampires are secluded in Victorian-style London townhomes or attending American high schools, they all seem to share certain threads of continuities that have remained uncut even as the definition of a ‘vampire’ evolved. The first (and most outwardly obvious) is style. Edward Cullen, Damon Salvatore, Count Dracula, and Lestat de Lioncourt are all very different characters, but the one thing they have in common is a dangerous yet appealing demeanor inherent to their vampiric nature.

The other, less obvious similarity, is deception. All vampires seem permanently and hopelessly alone, and their outward appearance can seem like a way to distract themselves from the emptiness of an eternal life of murder, hunger, and death.

The versatility of the vampire has helped it to remain in the zeitgeist for centuries, but the backbone of that versatility is a set of struggles with purpose and meaning that will never stop being relatable.

As Stephen King wrote in his vampire novel, Salem’s Lot, “Alone. Yes, that is the keyword, the most awful word in the English tongue. Murder doesn’t hold a candle to it and hell is only a poor synonym.” Vampire stories have always turned a blacklight onto the human condition, illuminating the dark undercurrents that have been there all along.

“Alone. Yes, that is the keyword, the most awful word in the English tongue. Murder doesn’t hold a candle to it and hell is only a poor synonym.” – Stephen King, Salem’s Lot

Otho Valentino Sella is an Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.' Otho has always been fascinated by stories and storytelling, and he sees journalistic...